Co-missioners,

Today we send you the second half of Fred Niedner’s essay on “the sweet swap.” And again we add our hope that you’ll be able to join us at the end of January to hear Fred in person along with other gifted presenters, all of whom who will push to us think more sharply about the goods we’re given to deliver through the proclamation of the Gospel.

We also want to invite you to hear Fred Neidner and others speak at the Crossings Seminar, held January 28-30, 2024, at the Pallottine Retreat Center in St. Louis. Registration will open shortly, along with details regarding scholarships and discounts for attendees.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

Proclaiming the Sweet Swap’s Gift of Metanoia

How preaching can serve the church’s continual practice of shedding the false stories

in and by which we live, and inhabiting Christ’s story instead.

(Part Two of Two; continued from October 5th)

by Fred Niedner

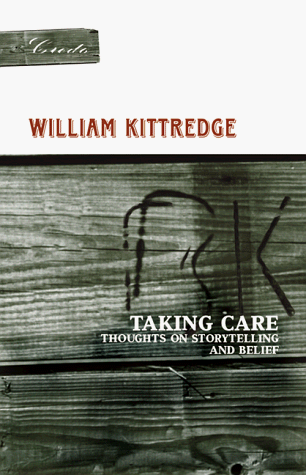

Few have written more insightfully about false stories by which individuals, communities, and even nations understand and direct their lives than William Kittredge in a book titled Taking Care: Thoughts on Storytelling and Belief (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 1999). Kittredge, born in Portland, Oregon, in 1932, eventually taught writing at the University of Montana for 30 years, but he grew up the heir to a 33-square-mile cattle ranch southeast of Eugene, Oregon, and took a degree in agriculture at Oregon State University. He had every intention of living out his family’s story. They understood themselves as independent, self-reliant westerners devoted to taming the wild land which their forebears had wrested from the benighted, inefficient, indigenous peoples who had no interest in improving it or making it productive. They built dams, developed irrigation systems, killed weeds with pesticides and wiped out coyotes with poison and bullets. Like so many who go to college, however, Kittredge found himself fascinated with unfamiliar literature and new questions about history and life. When he left school and his turn came to lead the next stage of his family’s ranching enterprise, he soon realized his people had not so much tamed the land as ruined it. In the process, they had disrupted countless lives, human and otherwise. Their seemingly noble mission was malignant, not merely vain.

He left it all behind, joined the army, gained admission to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, survived numerous personal and family crises, and started a teaching and writing career that gave him space to think and learn about life, faith, and what it means to be human. He writes mostly about “westerners” in the United States and the stories by which they live, but his insights have the ring of universal application. This excerpt expresses some of Kittredge’s hard-earned wisdom:

Mythologies and community stories shape societies. A mythology is a story that contains implicit instructions from a society to its members, telling them what is valuable and how to conduct themselves if they are to preserve the things they cherish.

The poet C.K. Williams once came to Missoula and spoke of “narrative dysfunction,” as a prime part of mental illness in our time. Many of us, he said, lose track of the story of ourselves, which tells us who we are supposed to be and how we are supposed to act. It doesn’t just happen to people, it happens to entire societies (for instance, in the United States during the Vietnam War). Stories are places to inhabit, inside the imagination (and places are understood in terms of stories). We all know a lot of stories and we’re in trouble when we don’t know which one is ours. Or when the one we inhabit doesn’t work anymore, and we stick with it anyway.

We live in stories. What we are is stories. We do things because of what is called character, and our character is formed by the stories we learn to live in. Late in the night we listen to our own breathing in the dark, and rework our stories, and we do it again the next morning, and all day long, before the looking glass of ourselves, reinventing our purposes. Without storytelling it’s hard to recognize ultimate reasons why one action is more essential than another.

Aristotle talks of “recognitions,” which can be thought of as moments of insight or flashes of understanding in which we see through to coherencies in the world. We are all continually seeking such experiences. It’s the most commonplace thing human beings do after breathing. We are like detectives, each trying to define what we take to be the right life. It is the primary, most incessant business of our lives.

And a few pages later . . .

We need to inhabit stories that will encourage us toward acts of the imagination, which in turn will drive us to the arts of empathy, for each other and the world. We need stories that will encourage us to understand we are part of everything, that the world exists under our skins, and that destroying it is a way of killing ourselves. We need stories that will drive us to care for one another, all the creatures, stories that will drive us to take action. We need stories that will tell us what kind of action to take.

We need stories that tell us reasons why compassion and the humane treatment of our fellows is more important—and interesting—than feathering our own nests as we go on accumulating property and power. Our lilacs bloom, and buzz with honeybees and hummingbirds. We can still find ways to live in some approximation of home-child heaven.

But there is no single story that names paradise. There never will be. Our stories have to be constantly reworked, reseen. [1]

Kittredge writes from a secular perspective, and he does not, at least in this work, offer stories in which we can live lives that aren’t bound for the Gehenna of his father’s and grandfather’s ruined ranchland and the environmental disaster his family’s seemingly noble myth and vision enabled. Translated into the theological categories of the law’s diagnosis and the gospel’s prognosis, however, he aptly describes the cunning deceitfulness and deadliness of the false narratives we craft for ourselves. In our stories, we are always the good guys. We become geniuses at justifying ourselves and blaming all that’s wrong with the world on others, and the few faults we see in ourselves are little more than occasional excesses to which those others have pushed us with their wrongheadedness. (Look what you made me do!)

While Kittredge doesn’t mention metanoia or how it comes about, his own story reveals when it happens, and what it must entail if it’s to open a way to new life. It happens when our story, or our entire working theology, the one in which we’re in control, or at least sit as the Almighty’s copilot, falls apart. We land in Gehenna. Or to paraphrase other biblical language, we find ourselves dead in trespasses, sins, and awash in putrid piles of poppycock we convinced ourselves to believe.

At this point, Kittredge asserts, we must find a new story in which to live. Metanoia of the sort that Jesus preaches, however, isn’t something we find. It finds us. It’s a gift. It begins with the news that we are not alone in the wasteland of Gehenna and God-forsakenness. He is with us—Jesus, the preacher, the crucified one, damned and dead as we are. And precisely here, he says “Come with me. Come live my story. Come, be my body, my flesh and blood, risen from the grave and on the loose in the world. Oh, we’re on our way to Jerusalem, sure enough, and they’re waiting for us there with nails and cross-beams, but along the way we have lepers to kiss, demoniacs that need a companion, hungry people with whom to share our manna, broken people to heal with kindness.”

Oddly enough, we are headed straight for Gehenna, but this time together. Jesus promised that the gate-keepers there can’t keep us out. Along with Jesus, crucified in the flesh but alive in the Spirit, we break in to preach to the spirits in prison, the ones who persisted in their own futile, damned stories and thus didn’t make the boat (1 Peter 3:17-22). What do we preach? Metanoia. Turn around. Let go. Let your old story die—and you with it, for that matter, and come with us as we follow Jesus to Jerusalem.

Perhaps some assurance of theological orthodoxy is appropriate here. This way of understanding the sweet swap and its gift of metanoia honors the death of Christ as fully necessary and sufficient for our salvation, and it comforts penitent hearts. There is no new life and no new story except for Christ’s death in our wretched, mucked up place. And there is no new story and no new life except we die with him, as most of us do in the waters of baptism, but only because we can’t do it in the same way that guy next to Jesus in Luke’s passion narrative managed. And it’s pure comfort for a broken, penitent heart when our old, once-glittering story proves deadly and we have nothing whatsoever to offer, that he says to us precisely then and there, “Come with me. My life is yours.”

In case it’s not yet clear, all this is also talk of “salvation by faith.” Faith is trust in a promise. Jesus says, “Come with me and we’ll live,” and assisted by faithful bystanders who strip off our stinking grave-clothes, we do just that. We come along, believing, giving our hearts to this last resort, to our hell-mate who invites us on a journey only he fully understands.

To be clear, it’s also a gift, this faith and our following. Experience will teach us over and over that we cannot by our own reason or strength believe in Jesus and his promise. Every day we will doubt, fall, give up, long to go back to our old vision and story, sick as it was. (It’s so easy to forget how thoroughly bondage once hurt and demeaned us.) But the Holy Spirit never quits calling, gathering us in, keeping us close, helping us see the sweetness and beauty of kissing those lepers and singing with people who once lived in tombs and howled at the moon. The consistency of both our failing and unbelief as well as the Spirit’s consistently faithful calling teaches us that the life of a Christian community is a matter of daily practice, daily dying and rising, daily reliance on one another for consolation and encouragement, daily metanoia. And this is precisely why we keep preaching and making sure to hear frequently and regularly this gospel story in which we live Christ’s life. Our old, Gehenna-bound story never dies. It tries continually and cunningly to haul us back in, trust it again, give it one more try. (This time you might get it right!) Against this incessant flow, the Holy Spirit, through the careful preaching of diagnosis and prognosis, pulls us back into the habitat of Christ’s story, his new life.

Not surprisingly, countless generations of preachers have discovered that funerals prove the occasions when it’s easiest to preach pure, comforting gospel. In the face of death, surrounded by Gehenna’s smoldering ashes, we get to tell grieving souls hungry for comfort and hope the story of how Jesus lived the life of our now-deceased loved one, knew his or her pain and sorrow and doubt and fear, and also how he or she got to live Christ’s life among us and became embodiment of gospel in our midst.

Every other occasion for preaching, usually thanks to the lectionary, offers preachers the requisite metaphors, imagery, and other raw materials for diagnosing some false story that most or all of us present have lived out, probably recently. In the same lessons, or nearby, there will also be glimpses of prognosis, the gift of the new story, Christ’s story, which we’ll find if we remember to look for metanoia, the entry and invitation to the new story, in the darkness where we find ourselves nailed to the ruins of our old story and its lies. Sometimes we’re in some wilderness where we think God can’t be. Or we’re on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho and come upon a be-ditched, half-dead person whose very presence creates an awful dilemma. Or we’re among the 99 who never stray or waste God’s time and are ready to judge not only the bloody maverick but the crazy fool who insists on finding everyone. Or we’re trapped with Jesus in the grip of some screaming mother with a sick child for whom we’d hardly have time even if she wasn’t one of those people.

No matter where we go, our old stories fail. We get nailed. And every time, in each such place, he says, “Now, friend, come with me . . .” Daily we rejoin his company. Most times, the Spirit uses faithful preaching to pull us back in, point us once more toward Jerusalem—and then a little beyond.

Valparaiso, Indiana

August 2023

Endnote

[1] Taking Care, pp. 52-53, 77-79, passim.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.