Co-missioners,

We’re not surprised that last week’s post prompted a couple of quick rejoinders from readers steeped in Lutheran confessional theology. The post’s author, Ron Roschke, is steeped in this theology too. You’ll discover this in today’s second part of his reflection on Romans Disarmed, the book he invites us to consider. We thank him heartily for prompting some thought and conversation that we in the Crossings orbit need to be having as we strive to honor Christ and serve the church as it’s presently configured.

We mentioned last week that Ron is producing weekly text studies—a lectionary blog, as he calls it. Its title is Wordloom. If you’d like to take a look at it, send him an email with your name and email address at wordloom.52 (at) gmail (dot) com. He’ll gladly add you to the distribution list.

Two other quick matters—

First, a reminder that registration for next January’s Crossings Seminar is now open. The topic is “Delivering God’s Goods.” The focus is on preaching and listening to preachers. Details are on our website. Yes, we’d love to see you there. Sunday evening, January 28, to Tuesday noon, January 30. Scholarships are available.

Second, we’re delighted to announce the imminent publication of Seminex Remembered, a booklet of recollections by Edward H. Schroeder. Next February marks the 50th anniversary of the unwanted launch of Concordia Seminex in Exile, or Christ Seminary—Seminex as it would come to be known. We are offering the booklet as a gift to anyone who participated along the way in this truly great school, and to anyone else who would simply like to learn about it. The booklet will be available before Christmas, or so we hope. To preorder your free copy, click here.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

Law and Gospel, Justice and Justification

Considering Romans Disarmed: Part Two

by Ronald W. Roschke

Last week I introduced you to the creative work of Sylvia C. Keesmaat and Brian J. Walsh in their book Romans Disarmed: Resisting Empire, Demanding Justice [Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2019]. Here they invite us to think about Paul’s letter to the Romans from the perspective of the first-century recipients to whom the letter is addressed. If you haven’t done so yet, I invite you to read (or review) last week’s article, where I describe how they approach their project.

We noted that Keesmaat and Walsh understand their reading of Romans as “disarming” the letter from the role it has played in theological battles that developed in the sixteenth century. In addition, this social/political reading of Romans allows twenty-first century readers like us to re-engage with the letter’s original message. Keesmaat and Walsh comment:

While the church has wielded this epistle as a sword within its own theological wars,

the letter itself has been strangely (and paradoxically) rendered powerless in the real conflict

Paul names to be at the heart of the gospel of Christ. While the church has been preoccupied with

the “justification” of the “sinner,” it has lost the radical message of how in Jesus Christ those

who are unjust are made to be just anew, equipped and empowered for lives of justice. (p. 252)

The Lutheran Confessions, following the insights of Martin Luther, are concerned precisely with “the justification of the sinner.” In fact, this becomes the pivot-point for the entire confessional movement. So what exactly is the relationship of Romans Disarmed to the concerns of the Lutheran Confessions? Is such an historical-critical reading of Paul’s letter mutually exclusive from reading it through a confessional lens? Are these two ways of understanding Paul actually pitted against each other?

Saint Peter Catholic Church (Millersburg, Ohio) – stained glass, St. Paul

From Wikimedia Commons

A key component in this book’s reading of Paul is that the focus shifts from justification to justice. The authors note that the Greek term used by Paul, dikaiosynē, refers to concepts covered by two Hebrew words: righteousness (tsedaqah) and justice (mishpat). Thus, it is linguistically legitimate and warranted to read the letter from either perspective. Keesmaat and Walsh emphasize that justice is extremely important to the house churches in Rome, living as they do under the intense oppression of the Empire. Therefore, Romans Disarmed centers its reading of Paul’s letter on that issue. But does a shift of perspective from justification to justice mark a change in how the letter functions theologically? To ask it in a way in which the confessions might frame it, does the analytical move from justification to justice also shift Paul’s letter from gospel to law?

The Lutheran passion for justification is centered on the commitment to understand God’s good news in Jesus as something that is entirely God’s doing from beginning to end. In Jesus, God has done what humans could never accomplish. We are loved unconditionally for the sake of Jesus, who has taken our human brokenness and absorbed it, carrying it to and through the cross. In order for this to be good news—in order for the gospel to “work”—it needs to be disconnected entirely from human striving. The confessions want this to be the guiding Christian theological principle from beginning to end. Even in understanding faith—which is the trust by which we sinners grasp the righteousness of Christ and make it our own—such faith must be God’s creation and God’s doing and not something that we create. It is a product of the Holy Spirit. We do not, we cannot, “believe ourselves” into God’s good news through our own efforts.

The struggle and experience of Martin Luther shaped this confessional insight into the absolute need of God’s initiative and action. As much as he desired and might have needed it, early on Luther could not love God or find God’s unconditional love for him. I think it’s helpful to understand this reality as something like a spiritual form of depression. Like depression, our inability to find and accept God’s love disarms the very mechanisms we need to be lifted out of despair. God has to do that for us. And God does that not only by loving us unconditionally—trading places with us by absorbing our brokenness and freeing us from it (in other words, gospel)—but also by using the law to help us analyze and unmask the ways in which we become complicit in our human attempts to avoid divine love in the first place. The law creates the interpretive context in which the gospel will make sense.

Most often, issues of justice seem to operate on the law-side of law and gospel. While justice seeks to create a system of wellbeing for the human family, the reality of human brokenness is so radical that ultimate goodness and wellbeing cannot be achieved through law alone. Human efforts at justice all too easily get twisted into oppression.

Nowhere is this feature unmasked more powerfully than in the story of Jesus, tortured and crucified as an act of “Roman justice.” One of the gifts of Romans Disarmed is its powerful ability to portray the menace of Empire. In this book, the systemic perversity of political power and ambition bent-in upon itself is unmasked. Keesmaat and Walsh are skillful in describing how this incarnation of malevolence transcends the historic boundaries of the Roman Empire and continues to operate powerfully throughout history and into our own day, including our own “American Empire.” Our contemporary hot-button political and social issues—racism; sexism; exploitation and disregard of Earth and its ecological wellbeing; violence against indigenous peoples, the poor, and the marginalized—are not just political and social issues; they are also profoundly spiritual and theological. They point to the mechanisms by which broken humanity gets disconnected from God.

It is important to recognize that from the perspective of the confessions, striving for justice—committing ourselves to building a better, more equitable world, as important as that may be—cannot achieve what the gospel alone can do. There is always a need for a deep spiritual transformation and a change of our status before God in order to address the deepest spiritual issues that beset us. Luther and the confessions often refer to our slavery to sin and death. So does Paul. So does Romans Disarmed. And in all three instances—confessions, Paul, and the book—the way forward out of slavery is through Jesus’ death and resurrection.

It is helpful to acknowledge that each of these three contexts occupies a specific and different place within human history. Each of them is constrained to understand the workings of law and gospel from within the cultural framework available to persons living in each of these three historical epochs. The confessions approach the task while having the tools made available after a millennium-and-a half of Christian theological reflection about what God was doing through Jesus. This viewpoint also depends deeply upon Martin Luther’s own personal spiritual, psychological, and theological wrestling with guilt and grace. Luther and the confessions are also heirs to the breakthrough in Western understanding of our humanity in the work of Augustine and the deepening sense of personal identity and selfhood he brought to this conversation.

However, this interpretive framework—available to Luther and the confessors—was not within Paul’s horizon. While applying these sixteenth-century insights as we interpret Paul confessionally is theologically legitimate, we cannot assume that Paul writes to the house churches of Rome as if he and they share and embrace sixteenth-century assumptions about human nature. I think that disambiguating this dilemma is part of the program that Keesmaat and Walsh undertake, asking us to look at how a first-century author and audience would hear and understand these words; this is part of what Romans Disarmed addresses in its shift from justification to justice.

For all three—the confessions, Paul, and Romans Disarmed—the ultimate answer to our human dilemma is found in the person and work of Jesus. That is “a given.” Confessions, Paul, and the book have their own distinctive ways of addressing that; they approach the issues from specific perspectives. Keesmaat and Walsh consistently invite their readers into the tasks of doing justice. The confessions, however, invite us to recognize that doing justice will not and cannot liberate us from our deepest spiritual dilemmas—Jesus is needed for that. I don’t think Keesmaat and Walsh would disagree with that; what they ask us to acknowledge is that imposing sixteenth-century perspectives on first-century documents may “take them hostage” and make it more difficult to read Romans from its own historical context.

And we Lutherans can affirm that pursuing justice is a necessary part of the Christian life. I always love the way Gerhard Forde expressed it—paraphrased—“There are two important questions for us to consider. First, what do we have to do to get right with God? The correct answer is: Absolutely nothing; God has done it all through Jesus. But the second question is also important: Now that you don’t have to do anything, what are you going to do?” Pursuing justice definitely should be on that list.

So back to our original question: From the perspective of the confessions, does reading Romans from the perspective of justice rather than justification push Paul’s thoughts from gospel into law? And the answer: It all depends…. If we understand justice as the path by which humans can make themselves right before God, then the gospel is compromised, and we are left only with the condemnation of the law.

I don’t think that is the program of Keesmaat and Walsh, however. Consistently, they name the death and resurrection of Jesus, not human striving, as the way in which God addresses the oppression experienced by the Roman Christians. The authors are not Lutherans and so they do not bring our confessional language into their historic reading of Paul. I don’t think we should expect them to do so. But it is a small step to use the approach of Keesmaat and Walsh in order to describe the Great Exchange, so central to Lutheran theology. Jesus, by maneuvering his own story to end his life on a Roman cross, totally immerses himself in solidarity with all who suffer the violence of the Empire. Because he absorbs that violence into his very self, his resurrection becomes a victory and a word of hope for all who likewise are trapped in that violence. Indeed, in Jesus a new day already has begun. Keesmaat and Walsh can help us articulate that in cultural/political terms!

Paul cannot be a sixteenth-century confessing Lutheran. Those insights lie a millennium-and-a-half ahead of him. His letter deserves to be read in its own historical context. That does not undo the amazing insights that Christians in the sixteenth century and beyond bring to this text. It does not invalidate twenty-first century Lutherans taking advantage of the brilliance of that analysis and using it for theology and life.

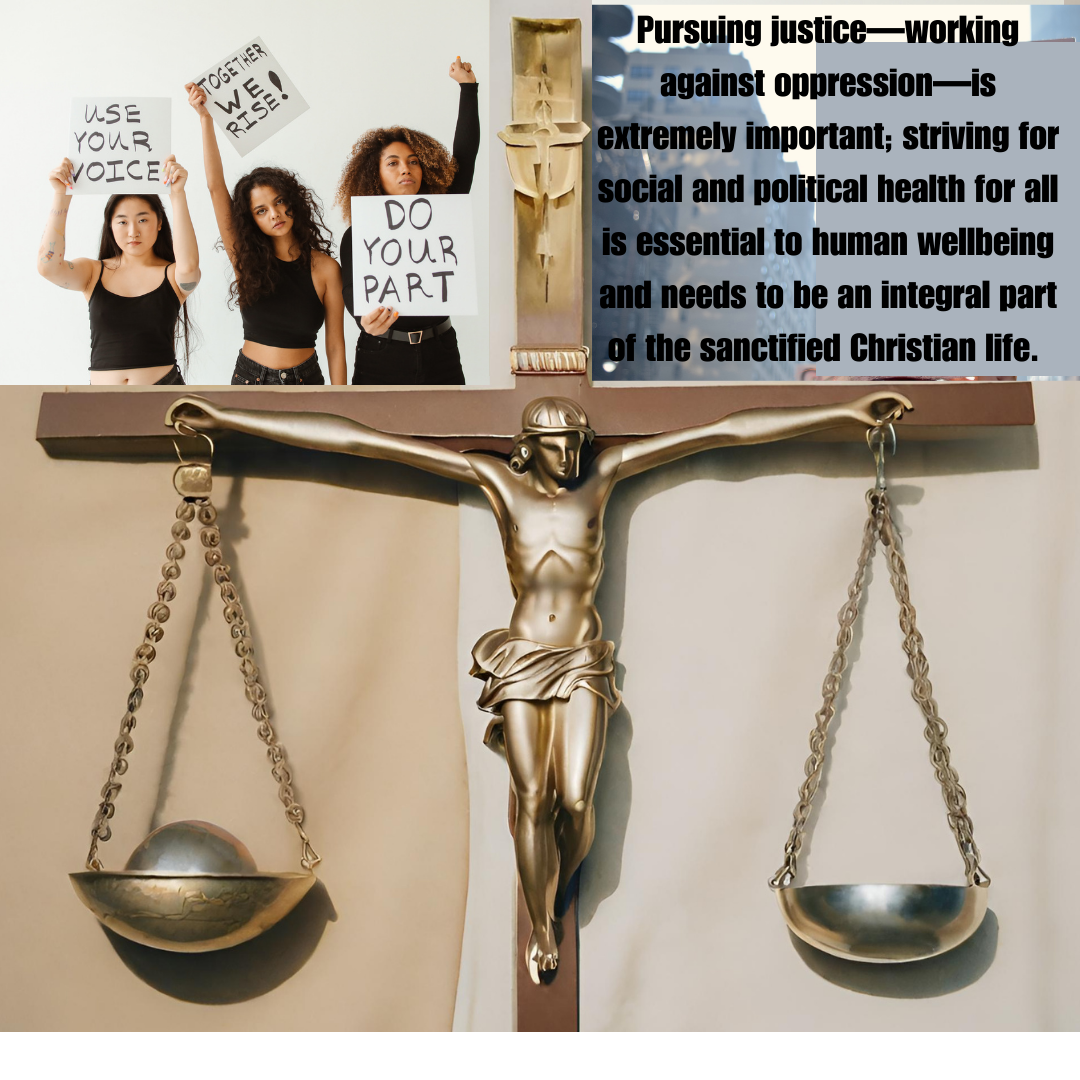

And pursuing justice—working against oppression—is extremely important; striving for social and political health for all is essential to human wellbeing and needs to be an integral part of the sanctified Christian life. Romans Disarmed has a great deal to teach us about all of this. There’s lots more to consider and discuss, and this book is a great place to begin.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.