Co-missioners,

This past February 20 featured one of the biggest gatherings yet for an online Crossings event. It was the second of two episodes in our Table Talk series devoted to the fiftieth anniversary of Seminex. Over twenty participants were asked to offer brief reflections on the following questions:

- What was Seminex really about, and why?

- How has Seminex affected your understanding of the church and its mission?

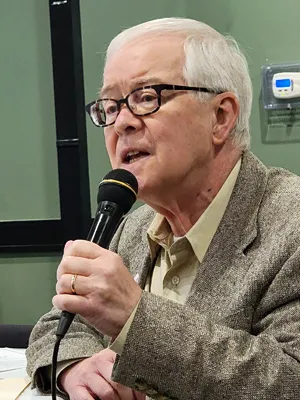

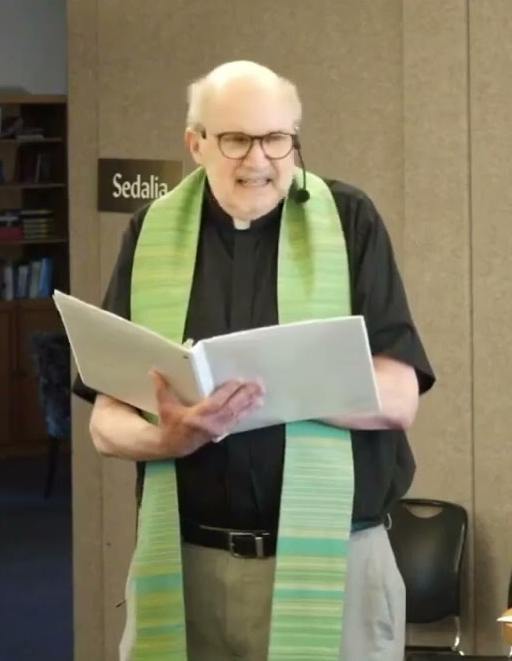

Today we bring you three of these reflections. They come from Gerald Mansholt, Ron Neustadt, and Ron Roschke, all of whom graduated from Seminex and are now retired from pastoral careers spent mostly within the ELCA. Along the way, Pr. Mansholt served as bishop for two ELCA synods and Pr. Roschke as a bishop’s assistant for another. Pr. Neustadt has been a longtime anchor of the Crossings Community.

Every person caught up in an event has their angle on it. We hope that by sharing several of these over the course of this year we will enrich your understanding of what once happened in Seminex and what its import might be for the church’s life today.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

More Reflections on Seminex

by Gerald Mansholt, Ron Neustadt, and Ron Roschke

To the questions—

- What was Seminex really about, and why?

- How has Seminex affected your understanding of the church and its mission?

+ + +

Gerald Mansholt—

I think it was Richard Caemmerer who said the Missouri Synod had always lived with a tension between two forces, those who were exclusivists, wanting to keep the synod pure and undefiled, and the inclusivists, who were open to others, at least other Lutherans if not also other Christians.

From its inception the Missouri Synod had presidential leadership that made sure both were represented on boards and committees. I remember Caemmerer specifically mentioning Oliver Harms (1962-1969) and John Behnken (1935-1962). Note that Behnken served for nearly 30 years. James Burkee has shown definitively in his book, Power, Politics and the Missouri Synod, what we as students as well as many pastors and lay leaders knew, namely, that Jack Preus had orchestrated a political take-over of the Church. Rather than working through the theological issues by engaging in dialogue and study, the leadership used tactics to instill fear and push a political agenda in the name of purity.

I had found a fresh wind blowing in the freedom of the Gospel as articulated by the seminary faculty majority, a freedom I have come to understand more clearly over the years in the Lutheran Confessions and writings of Martin Luther. The fresh wind opened the Holy Scriptures in new ways, took science seriously, embraced the possibility of women (and others) in ministry, was willing to engage the issues of the world around us, and kept the Good News of God in Jesus Christ central.

For me the whole experience clarified the sense of call to ministry and helped me understand the Church as formed and called to participate in God’s mission in the world. I remember a Seminex publicity flier that spoke of getting one’s theological education in a crucible of conflict. That was the case for me. There was a testing, a challenge during my first call in Oklahoma, because I was a Seminex graduate. While other first call pastors were learning how to do programming, the validity of my ordination was being challenged and my theology questioned. Those were days, Ralph Klein said, one would not wish on anyone; yet no one wanted to miss them for anything. In those hard and difficult days my identity as a pastor and my sense of call was forged and centered in the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

+ + +

Ron Neustadt—

From the very beginning there have been many and various answers given to the question of what Seminex was really about. And, from the beginning, some of the answers to that question have been sincere and some have been cynical. It was all political, say the cynical – nothing but a power struggle.

Or they may say it was about long-standing resentments that had built up in the rather closed universe of the Missouri Synod’s prep schools. Or they may say Seminex was simply a religious / cultural expression of the turmoil that was going on in the whole American society in the 1970s. It was the age of long hair and Viet Nam war protests, the age of conflict between WWII veterans and their sons.

Or they may say it was about personality clashes within the faculty or competition among academics who lived with their heads in the clouds – as if Seminex were not about something practical, not about something that mattered in the “real world”.

Others may be less cynical but still believe that Seminex was the result of an historical progression of Lutheranism in the US away from being an immigrant, ethnic church toward being more ecumenical and more exposed to other than “in house” theologians. They will point to how the LC-MS had begun to call more seminary professors to Concordia – St. Louis who had received their doctoral education, not from Missouri Synod schools but from other educational institutions and seminaries.

But, as popular as some of these theories may be, I don’t think any one of them is sufficient to explain the phenomenon of Seminex. And I don’t think any one of them can explain the willingness of so many to risk everything – their professional careers, their income, their housing, their pensions, their relationships with their parents, or with their in-laws, or with their extended families.

There was something bigger at stake.

What was at stake, I believe, was the very essence of the Church’s proclamation. We who were students had heard our teachers teaching us honest to God Good News.

And it rang true. To me, what my teachers were teaching was consistent with the Spirit of what I had been taught since I had been a child – even though some of those who had taught me would not be able to admit that. It was teaching that did not simply give us information about the Bible but actually opened the Scriptures to us. It was teaching that did not simply give us data about the history of the church or about the Lutheran Confessions, but that opened that history and those Confessions so that we could get a glimpse of the Christ who was at the center of that history and of those confessions.

How has all of that affected my understanding of the church and her mission? Answer: The need for reformation never ends. It continues to this day.

+ + +

Ron Roschke—

Seminex was never about one thing. There are several things we should have learned from our Seminex experience. First, we should now appreciate the incredible power of conservative movements—especially when they are joined to authoritarian leadership willing to bend or break, ignore or re-write the rules that protect the common good. Seminex wasn’t the first time that happened; it won’t be the last. But this is what happens when someone tries to make everything great again. And it becomes especially deadly when political ambition gets joined to serious distortion of the Christian faith.

The second thing we might learn from Seminex is that the gospel of Jesus Christ appears to have little or no power in stopping the steamroller of such conservative movements. The good news fails to hold off the damage that these juggernauts inflict upon individuals and institutions and the world. That was true in Germany in the 1930s, and in Missouri in the 1970s. And here, fifty years after Seminex, we may need to learn it all over again—very soon.

The third thing we might learn from Seminex is that this weakness of the gospel is exactly what the good news of Jesus is all about. Each painful iteration of the tragedy is a fresh demonstration of the way God chooses to manage our broken reality. It is, you see, the story of God in the person of Jesus; it’s about God’s unflagging solidarity with a suffering, broken creation—and a suffering, broken church. Those of us who see God through the cross and open tomb of Jesus keep finding this pattern repeating, over and over. Each time, the cross comes before the resurrection, and that always hurts. Dying and rising is not an easy way to move through life or through the world. But it is the only way to assure no one gets left behind.

This is the sign placed on all of us who walked through Seminex.

Experiencing this pain over and over puts us in the company of Jesus—the one who is the divine stamp, the minted coin of this curious God. Jesus is the one filled with grace and love, patience and hope. The church is his body—and therefore, the church is cruciform. If Seminex has taught us that, it is the greatest legacy for which we could hope.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.