Co-missioners,

Students of all ages are heading back to school this week in many parts of the U.S. It’s an apt time for Thursday Theology readers to do the same.

With this in mind, we send you the first installment of a six-week-long introduction to one of the fundamental documents that Crossings-style theology takes its clues from. It will serve for some as a refresher course, perhaps long overdue.

The document is the long Fourth Article of “The Apology of the Augsburg Confession”—Apology IV, to use the shorthand designation. Time was when every Lutheran seminary insisted that students read this closely. Some did. Of these, many struggled to follow the argument, let alone to grasp how much it matters to our thinking and talking today about God’s Gospel in Jesus Christ.

Our instructor these next several weeks is Paul Jaster. Earlier this year he wrote a reader’s guide to Apology IV designed specifically for those of us who follow Crossings and employ its method for analyzing a scriptural text. Our editor learned much as he reviewed Paul’s work. Be assured that you’ll learn too.

With this we urge you to blow the dust off your Book of Concord—to buy one, if need be; today’s standard edition by Robert Kolb and Timothy Wengert is the one to get—and dig in eagerly.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

A Crosser’s Guide to the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, Article Four: Justification by Faith Alone

by Paul Jaster

Introduction

At the heart of Crossings’ work is a Six-Step Method for understanding the Word and the World so that the benefits of Christ may abound. This method combines the key insight of the Lutheran Reformation of the 1500s (sola fide) with the medical model of diagnosis and prognosis for “crossing” the gospel message of Jesus Christ with the world in which we live today. In the first three steps, the “crosser” acts like a doctor diagnosing the external problem (Step One), the internal problem (Step Two), and the ultimate eternal problem (Step Three). And, then the crosser points to how God provides a remedy (a hopeful prognosis) “eternally” by sending Christ to do for us what we cannot do for ourselves (Step Four), how “internally” the gift of the Holy Spirit allows us to latch on to what Christ has done for us by faith (Step Five), and how “externally” this results in a faith active in love that loves God by joyfully serving our neighbor (Step Six).

The critical point in this six-step method is moving from Step Four to Step Five, which is where one “internally” latches on to God’s “eternal” remedy in Christ by faith. This step is the same in every crossing and it is anchored on the key insight of the Lutheran Reformation: namely, that we enter a healthy relationship with God (are justified) by faith alone. And not just any faith, but faith in God’s promises made in the crucified and risen Christ, which faith then receives the benefits Christ brings.

Presentation of the Augsburg Confession – From Wikimedia Commons

This central insight is extolled and explained in the bold witness the followers of Martin Luther made in 1530 in the Augsburg Confession, particularly as it was defended by Luther’s colleague, Philip Melanchthon, in the Apology of the Augsburg Confession. “Apology” here does not mean “I am sorry, let me take it back.” It means defending the faith expressed in the Augsburg Confession from the vicious attacks of the Confessors’ opponents. The most important part of that defense is Article Four on the topic “Justification by Faith Alone,” which is always the fifth and most critical step in the Crossing Method. So, a solid understanding Apology Four is essential for anyone using the Six-Step Crossings Method.

A Response to a Response to a Response: The Apology is a response to a response to a response. It is part of a larger set of events. In 1530, Emperor Charles V called a formal imperial meeting in the German city of Augsburg. He demanded the Evangelical princes and cities of his empire to justify their alterations in church practice. Martin Luther himself could not attend because he was an outlaw and could be imprisoned and burned as a heretic. So, Luther depended on his supporters, whom he coached from Coburg Castle, which was as close as he could get without leaving Saxony. This moment was important because now powerful princes and free cities were owning Luther’s movement for themselves.

Response #1: The Augsburg Confession (AC): At first Luther’s supporters had intended to make a statement about only those practices they considered to be abuses (AC, Articles 22-28). But when Luther’s infamous nemesis John Eck accused them of all kinds of heresies from the past, they decided they needed a more complete statement of faith in order to demonstrate their orthodoxy in accordance with the Scriptures and the early church fathers (AC, Articles 1-21). Their response to the emperor’s request was a document that became known as the Augsburg Confession. Robert Kolb and James Nestingen see this act of confession as “the birth certificate and charter of the Lutheran Church” (Sources and Contexts of the Book of Concord [Fortress Press, 2001], vii). Those who submitted, signed, and stood aligned with Augsburg Confession are called the “Confessors.” This means Christians who take the witness stand in a court of law to “stand up” for their Christian faith at great risk to themselves in the face of violent opposition. The Confessors prepared both a German and a Latin copy of their confession. They orally presented the German copy before the emperor on June 25, 1530. Afterwards the emperor reached out for and kept the Latin copy.

Confutatio Augustana and Confessio Augustana presented to Charles the V in 1530, Catholic and Lutheran sides presenting documents at the Diet of Augsburg.

From Wikimedia Commons

Response #2: Their Opponents’ Confutation: The Confessors’ opponents did not compose a confession of their faith, as had been expected. Rather, Charles V created a commission to refute the Lutheran statement of faith. This commission consisted of about two dozen theologians, including the bitterest personal enemies of Luther led by John Eck. The commission fashioned a Confutation of the Augsburg Confession. To “confute” means “to overwhelm by a vigorous counter-argument.” The Confutation was officially accepted by the emperor on August 3, 1530. Charles V declared the final revision of the Confutation as his faith and demanded that the Lutherans accept it and agree not to publish anything against it before giving them a copy.

Response #3: The Apology of the Augsburg Confession (Ap): At that point, Philip Melanchthon and others, working off of stenographic notes, wrote an Apology of the Confession, defending it against the false accusations of the Confutation. Instead of yielding to the emperor’s demand, the Confessors delivered the Apology, which the emperor would not receive. On September 22, the emperor gave the Lutherans until April 15, 1531 to submit or lose life, goods, and honor. After some time, Melanchthon secured a copy of the Confutation and revised his Apology accordingly several times. In 1532, the Lutheran Estates adopted the Apology as “a defense and explanation of the Confession.” For the text of the Confutation and more background see Kolb-Nestingen, Sources and Contexts of The Book of Concord.

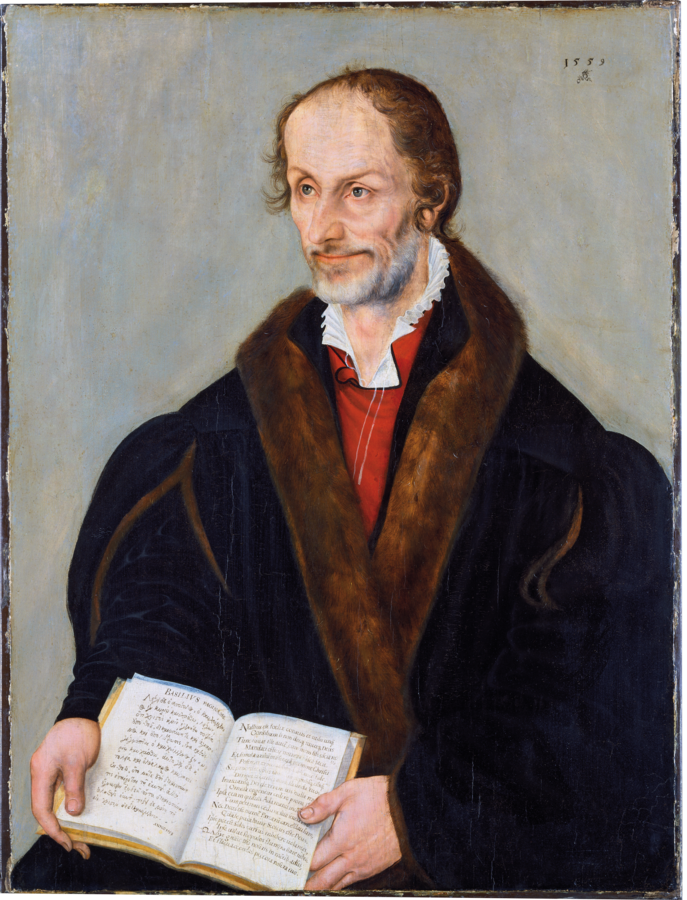

Portrait of Philipp Melanchthon

From Wikimedia Commons

The Challenge of Apology Four for Crossers Today: As said above, understanding Apology Four is foundational for the Crossing Method, especially for Step Five of the Crossing Method. But reading Apology Four is challenging because it is long and repetitive. This is because Melanchthon structured his argument in the form of a late-medieval scholastic disputation. In a disputation, first there are some preliminaries such as (1) a statement of the question at hand, (2) the sources for one’s position, (3) definitions, (4) a statement contrasting your position with your opponents’ position from your perspective, and a critique of your opponents’ position. This all takes place in the Apology between paragraphs 1-60. Secondly, there is a systematic development of your main argument, which happens between paragraphs 61-182. Finally, there is a detailed response to the arguments of your opponents, paragraphs 183-400. This Crosser’s Guide to Apology Four is designed to help the reader navigate these three major steps.

First & Second Editions: The first edition of the Apology appeared at the end of April or early May 1531. It is called the quarto edition because of its large printing format. An improved second edition, called the octavo edition because of its smaller format, was published in September 1531.

The English Text: This guide follows and cites the English text in the Robert Kolb and Timothy Wengert edition of The Book of Concord (BOC, 2000) because it is the most recent English version and it includes the additional material from the octavo edition. Items in this guide are treated in order, page by page. Numbers in [brackets] indicate the paragraph numbers in the margins of the text for reference purposes. In some places, I have drawn upon the translation by Jaroslav Pelikan in the Theodore Tappert edition (BOC, 1959). That edition is based on the earlier quarto edition and features the same paragraph numbering system where the editions overlap and so can be used with this guide also.

One Beef, but a Biggie: I have but one beef with BOC, 2000, and it is a major one. It is over the proper translation of the Latin word debet. Debet and its word group can be heard by our English ears in a variety of ways, such as:

-

- “should” (a suggestion, or the way something ought to happen but may not depending on the choice of the person involved),

- “must” (moral imperative or else there will be painful penalties),

- “must necessarily” (an essential requirement or else a key ingredient is missing, like yeast from a loaf of bread), or

- “bound to” (natural occurrence out of the very nature of the matter at hand).

These distinctions are essential in two critical places. The first place is when Apology Four says all Scripture must necessarily (debet) be divided into these two main topics: the law and the promises. I treat debet here as “an essential requirement.” The second place is when the Confessors talk about the new obedience and say that personal faith is bound to (debeat) produce good fruit or works or love. It is “a natural occurrence out of the very nature of personal justifying faith.”

The Kolb-Wengert edition usually translates the word debet and its word group as “should” in these places. But my teacher Arthur Carl Piepkorn, professor of systematic theology at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, who was an expert Reformation paleographer (one who deciphers handwritten early Lutheran manuscripts) and who was the translator of the Formula of Concord in the BOC, 1959, always insisted that the word debet in these places should be translated “must necessarily” and “bound to” respectively. For him, dividing all of Scripture into law and promise (gospel) is not an option, it is essential to interpreting the Scriptures. Nor is it “iffy” whether “good fruit in works of love” will follow “faith” (AC VI). It is neither a suggestion nor a moral imperative. He insisted it was bound to happen naturally.

Piepkorn based his latter translation on that preaching of Luther which echoed our Lord’s own parable that good fruit must necessarily come from a good tree just naturally, “out of the good treasure of the heart” (Luke 7:43-45; Matthew 7:15-20). He may also have found confirmation for this translation in the Formula of Concord, Epitome, IV, 5 which begins “This is our doctrine, faith, and confession: That good works, like fruits of a good tree, certainly and indubitably (indubitato) follow genuine faith—if it is a living and not a dead faith.”

Another portion of the Formula of Concord called the “Solid Declaration” is also worth quoting: “Therefore, faith must be the mother and the source of those truly and God-pleasing works, which God wants to reward in this world and the next. For this reason, St. Paul calls them true fruits of faith or of the Spirit [Galatians 5:22; Ephesians 5:9]. For, as Dr. Luther writes in the preface to St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans [in 1522], ‘Faith is a divine work in us which changes us and makes us to be born anew of God [John 1:12-13]. It kills the old “Adam” [the old person in us] and makes us altogether different people, in heart and mind and all powers; and it brings with it the Holy Spirit. O, it is a living, busy, active, mighty thing, this faith. It is impossible for it not to be doing good works incessantly. It does not ask whether good works are to be done, but before the question is asked, it has already done them, and is constantly doing them.’… ‘Thus, it is impossible to separate works from faith, quite as impossible as to separate heat and light from fire’” [Solid Declaration IV, 9-12].

Consequently, in my citation of Kolb & Wengert’s English translations I indicate in brackets where the Latin word group of debet occurs and its alternative meaning “must necessarily” or “bound to.” In places where I wish to emphasize a particular theme, such as the theme of necessity and what my seminary professor Ed Schroeder called “the double dipstick test” (as described below), I have drawn attention to it with bold type. For easier reading, I place Bible citations in italics.

—to be continued

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.