Co-missioners,

The end is in sight. Paul Jaster will walk us today through Philip Melanchthon’s rebuttal of his opponents’ claim that he and his fellow-confessors have either made a hash of key Biblical texts or ignored them completely. God says a person needs more than faith in Christ to wind up justified—so the opponents argue.

“Think again,” Melanchthon responds.

With such thinking in mind we invite you not only to read closely today but also to mark your calendars for a Crossings seminar at the end of next January. It starts on the evening of Sunday the 28th and wraps up at noon on Tuesday the 30th. Location: the Pallottine Retreat Center in Florissant, Missouri, a northern suburb of St. Louis. We’ll be exploring how the sparkling insights of Apology IV drive the kind of proclamation the world will need in 2024. Our topic: “Delivering God’s Goods.” Much more on this in coming days.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

A Crosser’s Guide to the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, Article Four: Justification by Faith Alone

by Paul Jaster

(Fifth of Six Installments, continuing from September 14)

Part Three: Response to the Arguments of the Opponents

As Melanchthon has already noted [61], the last part of a scholastic disputation is to respond to the arguments of one’s opponents. Here this means addressing the biblical proof texts that the Confutators are using against the Confessors. However, Melanchthon does much more than just “object to and correct” their biblical interpretation. Rather, like a doctor, he examines and “diagnoses” the hardness of their hearts and points out their total “lack of love,” the very love they so vociferously proclaim. Specifically,

-

- They corrupt many passages, because they read into them their own opinions.

- They impose excessive burdens on the people.

- They judge the conduct of their teachers too severely.

- They preach so much about love when they never show it.

- They are breaking up churches.

- They are writing laws in blood.

- They are slaughtering good people if they even slightly intimate they do not approve of some abuse.

- They have no more understanding of love than the walls of a house that bounce back an echo.

- The greatest tragedies arise from the most trifling offenses.

- Many heresies have arisen in the church simply from the hatred of the teachers [235-236].

But, in making his diagnosis of his opponents’ lack of love, Melanchthon also proposes a “remedy,” his prognosis:

-

- It is not possible to preserve tranquility, unless people overlook and forgive certain mistakes among themselves.

- The integrity of the church is preserved when the strong bear with the weak, when people put the best construction on the faults of their teachers, and when the bishops make some allowance for the weakness of their people.

- Tumults and dissensions would die down if the opponents did not so harshly demand compliance with those traditions that are useless for piety.

- Dissensions should be settled by fairness and kindness on our part.

- “Love covers a multitude of sins” – even though offenses flare up, love conceals them, forgives, yields, and does not carry everything to the fullest extent of the law.

- Preserving public harmony cannot last long unless pastors and churches overlook and pardon many things among themselves.

- Since faith is a new life, it necessarily produces new impulses and new works.

The issue is not simply a matter of biblical interpretation. It is a matter of the heart. It is a matter of love. It is a matter of peace and tranquility in both church and state.

The Law and the Gospel – Lucas Cranach

From Wikimedia Commons

Drawing upon the distinction the Confessors made between the law and the promises (gospel), Melanchthon points out that his opponents “quote passages about the law and works but omit passages about the promises” [183]. He writes, “To all their statements about the law we can give one reply: the law cannot be kept without Christ. And if any civil works are done without Christ, they do not conciliate God. Therefore when works are commended, we must add that faith is required—that they are commended on account of faith, because they are the fruits and testimonies of faith.” “One has to (necesse est) distinguish the promises from the law in order to recognize the benefits of Christ” [184]. The law and the promises need to be ‘rightly distinguished’ with care” [188].

For the term “rightly distinguished” Melanchthon uses the Greek word orthotomounta (ὀρθοτομοῦντα) from 2 Timothy 2:15 “Do your best to present yourself to God as approved by him…rightly explaining (orthotomounta) the word of truth.” Orthotomein literally means “cut a road across country (that is forested or otherwise difficult to pass through) in a straight direction so that the traveler may go directly to [their] destination.” Thus, in 2 Timothy 2:15 it means “guide the word of truth along a straight path…without being turned aside by wordy debates and impious talk” [BDAG].

If, as the Confutators claim, the forgiveness of sins depends on the condition of our works (doing what is in you), it would be completely uncertain, as it was for the anxious monk, Martin Luther. “For we never do enough works” [187]. “Good works are to be done because God requires them. Therefore they are the result of regeneration.” Good works must follow faith as thanksgiving toward God. “Good works ought to follow faith so that faith is exercised in them, grows, and is shown to others, in order that others may be invited to godliness by our confession” [202].

The Confessors God-damn their opponents’ “wicked notions about works” for four reasons. Reason one and two are the double dipstick test.

- These notions obscure the glory of Christ.

- They fail to find peace of conscience in these works, and instead instill terror and despair.

- They never attain the knowledge of God.

- Their ungodly opinion about works always clings to the world, rather than clinging to God’s promises in Christ [204].

The Confutators’ Proof Texts & The Confessors’ Rebuttals

As mentioned above, in this section Melanchthon “crosses” the Confutators’ biblical proof passages with the personal, political and social issues of daily life in a way that extols the promises of God and the benefits of Christ. This is the same goal that the Six-Step Crossings Method aims for.

1 Corinthians 13:2: “If I have all faith…but do not have love, I am nothing.”

Rebuttal: The Confessors also, like Paul, require love. As was said earlier, “the renewal and incipient keeping of the law ought to exist in us. Whoever throws away love will not retain faith…for that person does not retain the Holy Spirit.” But Paul does not say here that love justifies, that through it we receive the forgiveness of sins, that it conquers the terrors of death and sin, that it is set against the wrath and judgment of God, that it satisfies the law, and that we are acceptable to God because of it. To say this, as their opponents imagine, destroys the promise of Christ.

“The opponents corrupt many passages, because they read into them their own opinions rather than deriving the meaning from the texts themselves.” Paul is not talking about the manner of justification here, rather he is speaking about its fruits. Paul understands love to be the right way to behave towards neighbor and that faith (grasping on God’s promises in Christ) is the right way to behave towards God.

The truism: “When love is lost, the Holy Spirit is lost, and when the Holy Spirit is lost, faith is driven away” (1 Cor. 13:2), “If I…do not have love, I am nothing” [218-224].

1 Corinthians 13:13 “The greatest of these is love.”

Rebuttal: The Confutators argue that love is preferred to faith and hope and that the greatest and most important virtue should justify. But here Paul is speaking strictly about love for the neighbor; thus love is the greatest because it bears the most fruits. Faith and hope deal only with our responsibility to God whereas love has an infinite number of outward responsibilities towards others. The Confessors grant that love for God and neighbor is the greatest virtue in the sense that love is the greatest commandment (Matthew 22:37). However, just as even the first or greatest law does not justify in the least, neither does the greatest virtue of the law justify.

For there is no law that accuses more than the commandment that is the summary of the whole law, “Love the Lord you God with all your heart.” For who among the saints other than Christ dares to boast of having satisfied this law? However, there is one virtue that does justify and which receives the reconciliation given on account of Christ: that virtue is faith. [227a]

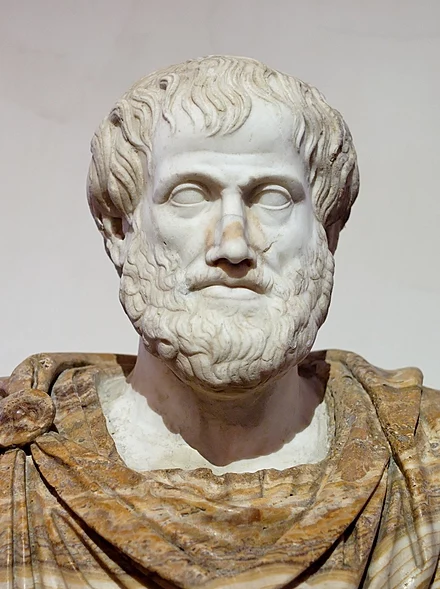

Bust of Aristotle – From Wikimedia Commons

To call faith the greatest virtue is no small thing. For, then yes! The greatest and most important virtue does justify. The scholastics based the ethics of their theology on Aristotle, who wrote “the book on ethics” called the Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle’s father and son were both named Nichomachus. The title could mean the ethics that Aristotle received from his father and/or that which he would urge on his son (or perhaps his most famous student Alexander the Great). Many thought that Aristotle already said everything that could be said about ethics and that there was nothing left to add. Part of Luther’s program was to free Catholic theology from Aristotle; but, on the other hand, there are moments when the Reformers found Aristotle useful. At the time that Melanchthon was writing the Apology, he had just begun lectures on the Nicomachean Ethics. It was part of the Wittenberg curriculum.

The key word in Aristotle’s ethics is “virtue,” which is outwardly acting on an honorable and praiseworthy “inwardly desire” (value) over a long period of time. It is a “lifelong habit.” For Aristotle the greatest virtue is philosophical contemplation (sophia, wisdom), no surprise for a philosopher. And as the greatest virtue, sophia was the telos (the ultimate goal, purpose, end) of a virtuous life. And it brought the greatest happiness (εὐδαιμονία, eudaimonia, as in life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness).

For the Confutators the greatest virtue is love, especially pious acts and religious deeds. The scholastics baptized Aristotle and then continued to use him focusing on moral precepts.

For the Confessors the greatest virtue is faith, which means faith is the telos (the ultimate goal in an ethical life). Faith is the greatest happiness. Faith is intended to be a “lifelong habit”: consistently acting over a lifetime on what true Christians should value most highly, the promises of God in Christ. Faith thus becomes an ethos, the ultimate ethos—a lifestyle, a habit, a way of life—although not a moralistic one.

The scholastics imagine that righteousness is our obedience to the law, just as the philosophers in ethics imagine it is moral precepts. But Paul protests loudly and teaches instead that being right before God is obedience to the promise of reconciliation on account of Christ [224-230].

Colossians 3:14 “Above all, clothe yourselves with love, which is the bond of perfection.”

Rebuttal: Using the Vulgate (fourth century Latin) translation of this passage, the Confutators reason that love justifies because it makes people perfect. But Melanchthon counters that Paul’s original meaning was about love for one’s neighbor. “There is no reason to think that Paul has attributed either justification or perfection before God to the works of the second table of the law rather than to the first. Besides, if love is the perfect fulfillment of the law and satisfies the law, then there is no need for Christ as the “propitiator” (one who makes a sacrifice on your behalf).” “Paul teaches that we are acceptable on account of Christ and not on account of the observance of the law, because our observance of the law is imperfect.”

Here Paul is not talking about the personal perfection of individuals. He is speaking about community in the church. He is talking about linking and binding together the many members of the church with one another like fashioning an unbroken chain. In all families and communities, harmony needs to be nurtured. It is not possible to preserve tranquility, unless people overlook and forgive certain mistakes among themselves. The same is true of the church.

“Harmony will inevitably dissolve whenever bishops impose excessive burdens upon the people and have no regard for their weaknesses. Dissensions…arise when people judge the conduct of their teachers too severely or scorn them on account of some lesser faults, going on to seek other kinds of doctrine and other teachers.” “On the contrary, perfection (that is, the integrity of the church) is preserved when the strong bear with the weak, when people put the best construction on the faults of their teachers, and when the bishops make some allowance for the weakness of their people.”

“Therefore, it makes no sense for the opponents to deduce from the word ‘perfection’ that love justifies, when Paul is speaking about the common integrity and tranquility of the church.”

“Moreover, it is disgraceful for the opponents to preach so much about love when they themselves never show it. What are they doing now? They are breaking up churches. They are writing laws in blood and are asking his most merciful prince, the emperor, to promulgate these laws. They are slaughtering priests and other good people if they even slightly intimate that they do not completely approve of some obvious abuse. These actions are not consistent with their praises of love; if the opponents lived up to them, both church and state would have peace. These tumults would die down if the opponents did not so harshly demand compliance with those traditions that are useless for piety—most of which are not observed even by those who most vehemently defend them.” The opponents have no more understanding than the walls of a house that bounce back an echo” [231-237].

1 Peter 4:8 “Love covers a multitude of sins”

Rebuttal: Peter is talking about love toward neighbor. “It could not have entered the mind of any apostle to say that our love overcomes sin and death; or that love is an atoning sacrifice on account of which God is reconciled apart from Christ the mediator.…” Peter is teaching that “if any dissentions flare up, they should be extinguished and settled by fairness and kindness on our part.” As we often see “the greatest tragedies arise from the most trifling offenses.” “Many heresies have arisen in the church simply from the hatred of the teachers. Thus, this text does not speak about one’s own sins, but that of others’ when it says, ‘love covers sins’…. That is to say, even though these offenses flare up, love conceals them, forgives, yields, and does not carry everything to the fullest extent of the law.” Preserving public harmony cannot last long unless pastors and churches overlook and pardon many things among themselves [238-243].

James 2:24 “You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone.”

Rebuttal: James here does not omit faith or substitute love for faith. He is saying the same thing that Paul did in 1 Timothy 1:5, “But the aim of such instruction is love that comes from a pure heart, a good conscience, and sincere faith.” James shows here that works of love follow faith and that faith is not dead but living and active in the heart. In 1:18 James says, God “gave us birth by the word of truth [the gospel], so that we would become a kind of first fruits of his creatures.” James is saying that faith which brings forth good works is alive. Since faith is a new life, it necessarily (necessario) produces new impulses and new works. James only describes the characteristics of the righteous after they have already been justified and regenerated.

“To be justified” here does not mean for a righteous person to be crafted from an ungodly one, but “to be pronounced righteous in a forensic sense” (sed usu forensi iustum pronuntiari) as in Romans 2:13. “Forensic” means in the manner a person is declared “guilty” or “not guilty” in a court of law. In court, everything depends on what the judge finally declares the reality to be.

Melanchthon at this point goes on to cite additional Bible passages and extend his argument. But these are the major Bible passages he addresses.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.