Why is God “Jealous,” Etc.

Co-missioners,

This week we send a smattering of items that landed recently in our editor’s “Passing Thoughts” file. Perhaps you’ll find them of interest. If so, there are more where these came from.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

Notes on God’s Jealousy; the Second Commandment; Not Hearing and Hearing; and a Chesterton Nugget

by Jerome Burce

I keep long lists of things that bear mention in a venue like this. A few of the latest—

- Why is God “Jealous”?

My preaching on the recent Trinity Sunday started not with trinity but, more essentially, with divinity. “What’s that?” as Luther puts it in his catechisms. Or better still, as in the Large Catechism, what is it “to have a god”? With that I took a sermonic moment or two to drape some 21st century clothes on Luther’s 16th century answer, which even as it stands is the best definition of “god-ness” out there. It tells the everyday, down-to-earth truth of the thing as all the musings of the philosophers do not. My god—any person’s actual god, the one he has in practice, not merely in theory—is whatever this person fears, loves or trusts more than anything else (LC, First Commandment). Which means, of course, that our own age and culture is as flagrantly polytheistic as any other age or culture. The only difference is that we don’t admit it. That’s as true of today’s would-be monotheists as it is of today’s would-be atheists. Who among us hasn’t set her deepest heart, or his, on something—many things—other than the One who said “Thou shalt have no other gods”? (For more along these lines, see Walt Bouman’s classic “Yes and No in a Taxicab”; and yes, it’s worth another look if you’ve seen it already.)

This got me thinking about something else the One and Only continues to say. “I the Lord your God am a jealous God….” This befuddled me when I was a kid. I couldn’t grasp why God should be jealous, especially when jealousy was talked about as something nasty that all right-thinking children would stay away from. Looking back, it dawns on that this was the boy approaching the God-question as the philosophers do, from top down instead of bottom up. Top-down starts with ideas. It imagines what deity must be or ought to be and assigns pre-defined attributes and characteristics accordingly. In the boy’s logic it works like this. “God is good. Jealous is bad. Therefore God can’t be jealous.”

This got me thinking about something else the One and Only continues to say. “I the Lord your God am a jealous God….” This befuddled me when I was a kid. I couldn’t grasp why God should be jealous, especially when jealousy was talked about as something nasty that all right-thinking children would stay away from. Looking back, it dawns on that this was the boy approaching the God-question as the philosophers do, from top down instead of bottom up. Top-down starts with ideas. It imagines what deity must be or ought to be and assigns pre-defined attributes and characteristics accordingly. In the boy’s logic it works like this. “God is good. Jealous is bad. Therefore God can’t be jealous.”

By contrast, bottom-up begins with facts on the ground. Take the ones that Exodus presents. “Here we are, sprung from Egypt, eating manna every day. No bricks to make or whips to drive the making. How did this come about? Because a particular god, one among the host that people worship, did for us what the rest of the gods wouldn’t dream of doing and couldn’t do in any case.” From that spring the conclusions: a) this God has a thing for us—a thing we can’t explain or account for, and yet it is because He Is. (I AM, says he, when he’s talking about himself.) b) When this God says he’s jealous of us, who can blame him? Has he not done for us what he alone would want to pull off or is able to pull off with the likes of us in mind? And should he catch us dallying with other deities that strike us momentarily as better looking or more malleable or a lot more fun, how can he not take umbrage? What use would he be if he didn’t? How could he be good?

For us today, the fact of facts on the ground is that God of Sinai hanging on a cross in the person of his Son. “For us and for our salvation,” as the Creed drives us again and again to confess. Of course this God is jealous, and fiercely so, where you and I are concerned. How could he not be when his goodness for us is a goodness that passionate? How can it not drive him nuts when he catches us in the embrace of those de facto deities that Luther names—money, power, prestige, the self—that can’t and will not do as God in Christ has done for us and is doing still in the person of the Spirit? “Have no other gods,” he tells us. Why? Because those other gods are no damn good. They don’t give a fig for us. They don’t deliver the goods that Triune God so wants us to have—and at his expense, no less. Since when have they forgiven a sinner or raised the dead? They wouldn’t want to. They don’t know how. No wonder Triune God is heaven-bent (as one might say) on keeping us from their clutches. Let’s expect him to be fierce in asserting his claim on us. Better still, let’s pray for the sense—the faith anchored in Christ—to thank him for his ferocity, his jealousy, and to praise him for it too.

Suddenly I wish someone would give us a hymn to sing that went like this: “Our God is a jealous God.” It would be so much more edifying than the one about how awesome he is.

- The Second Commandment: So Much More To It Than We Guessed

A year or more ago a colleague put me on to a podcast called “First Reading.” It features two young Old Testament scholars discussing the first of the Revised Common Lectionary texts for the forthcoming Sunday. Each episode lasts about fifteen minutes. They tend to be meaty and useful, also for Lutheran preachers which the podcast hosts are not.

A year or more ago a colleague put me on to a podcast called “First Reading.” It features two young Old Testament scholars discussing the first of the Revised Common Lectionary texts for the forthcoming Sunday. Each episode lasts about fifteen minutes. They tend to be meaty and useful, also for Lutheran preachers which the podcast hosts are not.

Back in March the featured OT text for the Third Sunday in Lent was the Exodus version of the Decalogue. To address this the hosts brought in a third scholar, Carmen Joy Imes of Prairie College in Three Hills, Alberta, a town northeast of Calgary. They spent forty minutes with her. Every second was worth it. Dr. Imes zeroed in on the Second Commandment and made it gush with a wondrous richness I hadn’t guessed was there. Never again will I be content to stick with the catechism when I talk about it. “No,” she said, “it’s not about cussing and swearing, as in ‘Don’t!’ but rather about spectacular mission, as in ‘Get busy and do!’ Among so much else, it got me thinking in fresh ways about what God is up to every time I baptize another baby.

I heartily commend the episode to your own listening. You’ll find it at firstreadingpodcast.com. Scroll down a while till you get to the episode entitled “Bearing God’s Name.” The text in question is Exodus 20:1-17. Again, do listen. The phrase “forty minutes wasted” will not cross your mind. I guarantee that.

- Sometimes They Just Don’t Listen…

A friend found this in a recent issue of The Christian Century and passed it along. You’ll wince too:

“A pastor…had just preached on loving your enemies, working from a text in the lectionary. After the service, an elder cornered him in the hallway. He was furious and said, “I don’t think it’s appropriate to preach on that subject when our nation is at war with violent Islamic terrorism! You shouldn’t mix religion and politics!’ ‘I’m just preaching what Jesus said,’ the pastor replied. ‘Well,’ the elder said, ‘I’ve always considered that a weak spot in Jesus’ teaching.’”

…And Sometimes They Do

Here’s a note I got a couple of weeks ago from a fairly recent member of my congregation—

“In Bible study classes, you have often asked us to say what “jumped out at you” in a passage. Well, now I want to tell you something that “jumped out” at me in your sermon this morning: You did not say that we “should trust” but you said “we get to trust”! It told me again, that if I am going to be a Christian, the first thing I need to do is Relax… This is such a liberating thought—it doesn’t all depend on me! And being reminded that God loves those other people as much as me is always good medicine for that ever-present ego-centric stance I am cursed with.”

To all my steady, stubborn colleagues of the Crossings-style pulpit: keep it up. You may not think it you’re getting through—I often don’t—but some way, somehow, you probably are. Another heart is being cheered as yours once was when someone else got through to you with a first strong whiff of unfettered Gospel. Soli Deo Gloria.

- A Thought for the Next Time You Go to Communion

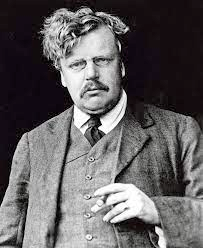

I took a brief dip in G. K. Chesterton a few days ago and ran across an essay critiquing Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, a 19th century translation by Edward FitzGerald of the 12th century Persian poet. Seems it was wildly popular among the jaded intellectual set of early 20th century England. Their offspring surround us these days. Here’s how Chesterton wraps things up.

“Jesus Christ also made wine, not a medicine, but a sacrament. But Omar makes it, not a sacrament, but a medicine. He feasts because life is not joyful; he revels because he is not glad. “Drink,” he says, “for you know not whence you come nor why. Drink, for you know not when you go nor where. Drink, because the stars are cruel and the world as idle as a humming-top. Drink, because there is nothing worth trusting, nothing worth fighting for. Drink, because all things are lapsed in a base equality and an evil peace.” So he stands offering us the cup in his hand. And at the high altar of Christianity stands another figure, in whose hand also is the cup of the vine. “Drink,” he says “for the whole world is as red as this wine, with the crimson of the love and wrath of God. Drink, for the trumpets are blowing for battle and this is the stirrup-cup. Drink, for this my blood of the new testament that is shed for you. Drink, for I know of whence you come and why. Drink, for I know of when you go and where.” (From Heretics, Ch. VII, “Omar and the Sacred Vine.”)

“Jesus Christ also made wine, not a medicine, but a sacrament. But Omar makes it, not a sacrament, but a medicine. He feasts because life is not joyful; he revels because he is not glad. “Drink,” he says, “for you know not whence you come nor why. Drink, for you know not when you go nor where. Drink, because the stars are cruel and the world as idle as a humming-top. Drink, because there is nothing worth trusting, nothing worth fighting for. Drink, because all things are lapsed in a base equality and an evil peace.” So he stands offering us the cup in his hand. And at the high altar of Christianity stands another figure, in whose hand also is the cup of the vine. “Drink,” he says “for the whole world is as red as this wine, with the crimson of the love and wrath of God. Drink, for the trumpets are blowing for battle and this is the stirrup-cup. Drink, for this my blood of the new testament that is shed for you. Drink, for I know of whence you come and why. Drink, for I know of when you go and where.” (From Heretics, Ch. VII, “Omar and the Sacred Vine.”)

Would that all of us could diagnose the spirits of our day with same sharp eye. Would that all of us exulted in the Promise with the same throbbing joy.

Enough for now. —JB.