Co-Missioners,

Steven Kuhl is our writer this week. He sends along a reflection he prepared for the congregation he serves in South Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He submitted it under the title “Sing to the Lord: What to do when Times are Tough.” We’ve taken the liberty of replacing that with one more suited to this audience.

Before we get to Steve, a quick announcement:

The date is July 16, two weeks from today. A group of younger pastors is going to meet over Zoom to launch a bi-weekly reading and discussion group devoted to Crossings theology—or “the Promising Tradition,” as Crossings’ co-founders Robert Bertram and Ed Schroeder liked to call it. They’ll be joined by older colleagues who studied with Bertram and Schroeder at Seminex, among them Jerry Burce and Steve Albertin. They heartily invite others who share this interest to join them too. Their initial project is to read through A Time for Confessing, a posthumous collection of Bob Bertram’s key essays. To learn more or to land a Zoom invitation, drop a note to Pr. Scott Benolkin.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

Crossing Our American Moment through Psalm 13

by Steven Kuhl

Photo by Colin Lloyd on Unsplash

In the Psalm for the Fourth Sunday after Pentecost (Ps. 13:1-6), we hear the writer crying out to God in frustration, if not despair, because he is being tormented by an “enemy.” (Let’s call him “David,” which is Hebrew for “Beloved.”) Although we don’t know the specific, outward details behind the lament, we certainly do know what David is feeling. He feels that God has “forgotten” him (v. 1), has “hid his face from him” (v. 2), because of how long he has been suffering at the hands of this enemy. Indeed, so overwhelming is the assault of this enemy, that David is not sure he will survive. For in his weariness, the very “light to his eyes” is fading and he is afraid that he is about to “sleep the sleep of death” (v. 3).

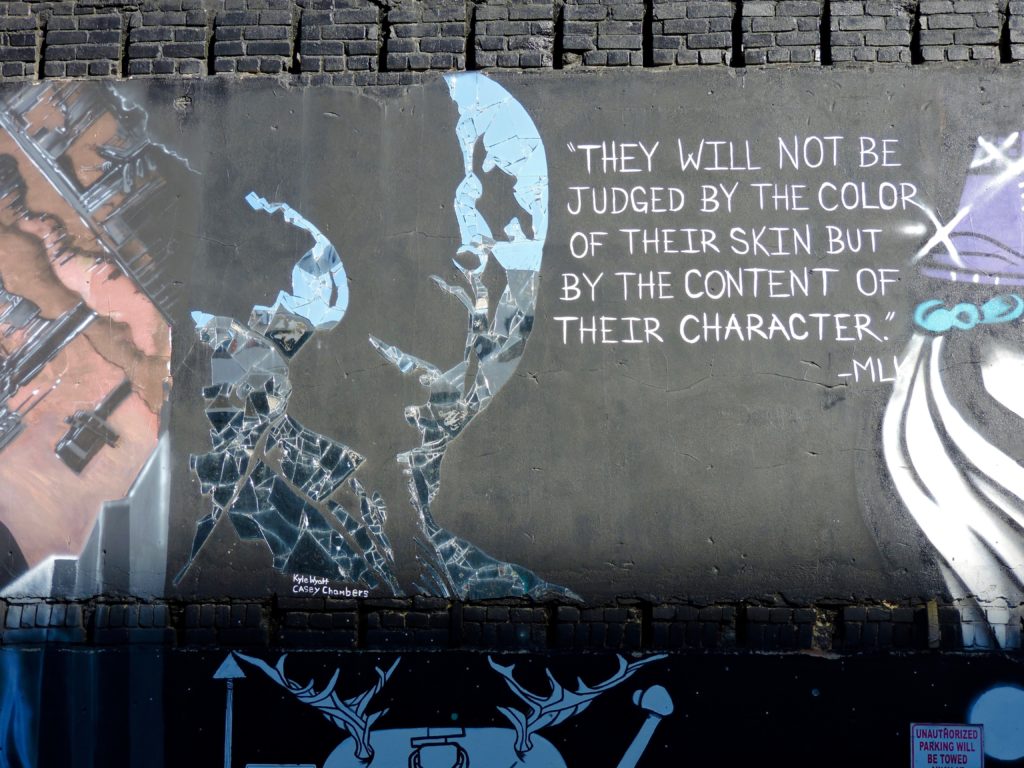

There are times when “enemies” arise in our midst and it feels as though they will drain the life right out of us. In our own time, I’m sure some feel that way about the coronavirus. Why, O Lord, is this terrible enemy still tormenting us? I know that many of our black citizens feel that way about the enemy of racism. In their protestations they are crying out, “How long, O Lord, how long must we endure this enemy. We have endured it for 400 years, we have called attention to it many times in our history, and, yet, it persists.”

Of course, as David also knew, the enemy could get a false sense of security because of the length of time it was able to inflict its will over against him. When the enemy is on top, it always declares, “I have prevailed” (v. 4). The enemy can even get so haughty as to think “I’m right and you are wrong, God favors me and not you.”

You would think that David would break under such humiliation and duress. But he doesn’t. Although the struggle against the enemy is real and fierce, his faith in God is stronger. Why? Because of God’s “steadfast love” for those who suffer at the hands of their enemy (v. 5) and because he knows the history of this God, that he is a God who gives “salvation” to his beloved (v. 5).

David is surely thinking here of Israel’s great story, the one about God delivering his people from bondage in Egypt. For 430 years, according to one count, they were slaves in Egypt (Exodus 12:40). For 430 years they cried out for deliverance. You know the story too. In his battle against an arrogant and haughty Egypt for the freedom of his beloved, God sends ten plagues upon Egypt. And even then, the enemy, Egypt, is not defeated until God drowns its army in the Red Sea, thereby stripping it, not of all life, but of its power to oppress.

Even though David hasn’t yet seen deliverance from his enemy, he trusts that God will deliver him, as God did his people, Israel, long ago. So, what does David do? “I will sing to the Lord” (v. 6), he says, as though the victory is already his and the bounty is already being shared.

As I read this Psalm, today, I can’t help but ask the question, who is “David,” the beloved, and who is the “enemy”? It seems to me “David” represents those who suffer at the hands of racism and the “enemy” is those who let it happen. Could it be that the coronavirus is but one of many plagues God keeps sending to America to show his might over us? Could the “troubles we see” be God’s way of slowly stripping away American power and prestige so that we might begin to see that “Black lives matter, too”? Could all this be God’s way of getting us to hear the biblical stories about, on the one hand, God’s preferential option for the oppressed, and, on the other, God’s patient pleading to oppressors to repent and change?

Please, don’t think for one moment that we should necessarily equate “David” with Blacks and the “enemy” with Whites. Things are not, well, that black and white. “David,” I think, represents those who would be “antiracists,” those who long to see racism end. They can be Black or White, as, indeed, they are when we look at the demonstrators today. The “enemy,” then, would represent those who would tend to be “neutral” on matters of racism. True, they don’t like it, but they aren’t quite willing to risk the kinds of change that are needed to deliver us from it. They cannot quite see that ending racism would be good for them, too.

This view of the “enemy” (those who are uncomfortable with racism but can’t free themselves from it) is like the view Martin Luther King, Jr. talked about in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and Ibram Kendi in his book, How to be an Antiracist. It’s important to note that neither one of them wants to destroy the “enemy” per se—not racism, that is, but racist people. They would much rather win these people over as friends. For the opposite of racism is humanism, the belief and practice that all people are equal in the eyes of God and are to be treated with equity in society and under the law.

This view of the “enemy” (those who are uncomfortable with racism but can’t free themselves from it) is like the view Martin Luther King, Jr. talked about in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and Ibram Kendi in his book, How to be an Antiracist. It’s important to note that neither one of them wants to destroy the “enemy” per se—not racism, that is, but racist people. They would much rather win these people over as friends. For the opposite of racism is humanism, the belief and practice that all people are equal in the eyes of God and are to be treated with equity in society and under the law.

It’s hard to tell, “how long” the Lord will put up with the enemy, with racism, in America. Remember, God put up with slavery in Egypt for 430 years. But also remember that when God ended it, it didn’t go well for the Egyptians. That’s because of the stubbornness of Pharaoh and the power structures of Egyptian society. In their obstinance they could not see the light that God was shining upon the problem of their oppression of the Israelites, let alone initiate constructive change. The lamentation of the oppressed people is that light.

Do we see this today?

Therefore, no one knows also how long it will take until David’s lament as sung by black and antiracist people in America will be met by change. But until it does, we can expect to hear them “sing to the Lord” (v. 6). Singing is a metaphor for demonstrating, demonstrating one’s faith that with God change will happen. That’s why singing is what protestors do when they get together. That’s why we have a whole genre of “protest songs.” That’s what Martin Luther King, Jr. did in the 1960s when he marched to the singing of “We shall overcome, someday”; and it is what today’s demonstrators still do, too.

For example, one afternoon, not far from the White House in Washington, D.C., the present-day protestors erupted into singing Billy Withers’ song, “We Need Somebody to Lean On.” What “Somebody” comes to mind when you hear this? Could this be what Bonhoeffer meant when he asked, “How can we speak/sing in a secular way/tune about God?” I think so. But, of course, timing and context are everything.

Photo by LeeAnn Cline on Unsplash

We the Church also know that much more can and needs to be said about this “Somebody” and his desire to “deliver us from the hands of our enemy.” Indeed, this Somebody has two ways of bringing deliverance. One is through the law and one is through the gospel. The first simply eliminates the enemy, or at least its power, as happened with Egypt; the latter actually sets its hope in liberating both the oppressed and the oppressor by turning enemies into friends. That latter kind of deliverance is what Martin Luther King, Jr. dreamed of. But here is the point: liberation, whether by law or by gospel, can only be spoken about in a secular way; and in Bonhoeffer’s meaning of the term, “a secular way” means from the perspective of our experience of life “in this age,” which is what the word “secular” literally means.

Of course, which Somebody the protestors long to leaning on is an open question. But that “openness” is something the Church and the Christian protestor can take advantage of. For without denying the legitimacy of the law’s right to eliminate the racist, the Christian chooses to lean on that “Somebody” who desires the conversion of both the racist and the antiracist to the gospel, so as to turn enemies into friends by the liberating power of repentance and forgiveness.

The name of that “Somebody” is Jesus Christ. He, too, like the law, can only be spoken of in a secular way, by reference to what he did “in this age.” This is how the creeds speak of him. “For us and our salvation,” says the Nicene Creed—cf. v. 5—Jesus was born in a secular way; suffered, was crucified and died in a secular way; and, yes, is raised from the dead in a secular way. Everything about this Jesus, this “Somebody,” involved him in acting on behalf of the oppressed in this age. But he saw oppression as being more endemic and more sinister “in this age” than we might think. The protestors point out the “obvious” oppression of racism and rightly name the people, the ideas, and policies that perpetrate it. Jesus would also point out how racism oppresses its perpetrators because the master perpetrator of racism is God’s “archenemy” known as sin or the devil. All racist acts, ideas, and policies are done under the duress or at the behest of the evil one, whether we are aware of it or not.

As Bonhoeffer asserted, the Church can only be the Church when it acts in a secular way, meaning, when it stands with the oppressed. In the sinister context of racism that means, on the one hand, standing with oppressive racists in order to help them repent of their “bondage to sin.” This help is given as the Church confesses for them, if not yet with them, as best as we can, the specifics of “what we have done and what we have left undone” by way of our Black brothers and sisters. On the other hand, standing with the oppressed also means standing with the oppressed antiracists, the Blacks and all who have already, themselves, passed through the crucible of repentance, and to help then forgive repentant racists as God has forgiven them.

To be sure, this is no easy task. It will take the help of the Holy Spirit entering into this age to make the message of repentance and forgiveness plausible, that is, as pleasing to us as it is of God. Therefore, by the power of the Holy Spirit, let us do as beloved David resolved to do. Let us sing to the Lord, beginning with the song the protestors sang, “We all need Somebody to lean on.” But let us not stop there. Let us name that Somebody in a secular way, in a way that speaks to now, the way David did. That Somebody whom we need is the One “who has dealt with [us] richly” (v. 6) in Jesus Christ, the One who promises forgiveness to the penitent, the one who stands with the oppressed. Singing to the Lord is not a distraction from the moment; true repentance is not a caving in to the inevitable. Rather, both are expressions of a well-founded hope that the long arc of history in Jesus Christ bends through justice towards mercy, through repentance towards forgiveness, through death towards resurrection—all of which adds up to a brand-new start, now, already, in this age, and in the age to come.

South Milwaukee, Wisconsin

June 28, 2020

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.