Hope and Meaning as the Virus Swirls

Co-Missioners,

From Bruce Modahl comes this second in our brief (?) series on the covid-19 pandemic. Need we repeat? Bruce edits our quarterly newsletter. He’s also the author of The Banality of Grace, published late last June by Cascade Books.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

Hope and Meaning as the Virus Swirls

by Bruce K. Modahl

I know he means well, the clergyman who responded to the Covid-19 crisis with the poem which begins,

Yes there is fear.

Yes there is isolation.

Yes there is panic buying.

Yes there is sickness.

Yes there is even death.

But,

They say that in Wuhan after so many years of noise

You can hear the birds again.

In our Chicago neighborhood you can hear the birds again. What you can’t hear are the voices of the children from the schools and playgrounds. No sounds come from the dog park where I used to pause to listen and watch. The young people who crowded the sidewalks and filled the restaurants and night spots made a great deal of noise They are gone and most of the people who worked in these places are without jobs. But you can hear the birds again.

Singing birds are not consolation for the overburdened ICU units in Italian hospitals. The nightly news shows medical workers in New York duct taping together homemade protective masks and shields. Medical workers in our country are updating their wills, securing guardians for their children, videotaping themselves reading children’s books so their children can hear their voices and see their faces during the long hours they are working and, worst case scenario, in case they die. There are places in Italy where they have run out of graves and stack caskets in the pews of shuttered churches. But you can hear the birds again.

Albert Camus published his novel The Plague in 1947. It offers a prescient description of what is happening today. The invisible contagion started small. The danger seemed unreal at first. It grew exponentially until it overwhelmed the community. There is little explanation for whom it affects, the virtuous and the vile, young and old, male and female.

Albert Camus published his novel The Plague in 1947. It offers a prescient description of what is happening today. The invisible contagion started small. The danger seemed unreal at first. It grew exponentially until it overwhelmed the community. There is little explanation for whom it affects, the virtuous and the vile, young and old, male and female.

Dr. Bernard Rieux, the main character in the novel, provides a counterpoint to what I perceive as the failings of the sentiment in the clergyman’s poem. Rieux works in quiet solidarity with the stricken community, tending to those who are sick and dying. He embeds himself with the people. But he is not a hero. He says, “This whole thing is not about heroism. It may seem a ridiculous idea, but the only way to fight the plague is with decency.” When asked what decency is Rieux replies, “Doing my job.”

Dr. Rieux is admirable, but Camus’s outlook for humanity is bleak. There is nothing beyond death. Since the meaning of anything is determined by its outcome, life is meaningless. Camus viewed life as absurd.

Alain de Botton, in an op-ed column in the New York Times, writes that Camus was drawn to the theme because he believed that “all human beings are vulnerable to being randomly exterminated at any time.” For Camus life is a hospice, never a hospital. De Botton claims Camus correctly sized up human nature. Camus said, “Everyone has it inside himself, this plague, because no one in the world, no one, is immune.”

So, we all have death in us. Rieux may not be a hero but his solidarity with those who are in death is preferable to one who would stand apart with the singing birds. It is preferable but not enough. Dr. Rieux is partly right; we all have death in us. He does not give voice to the hope that is also within us.

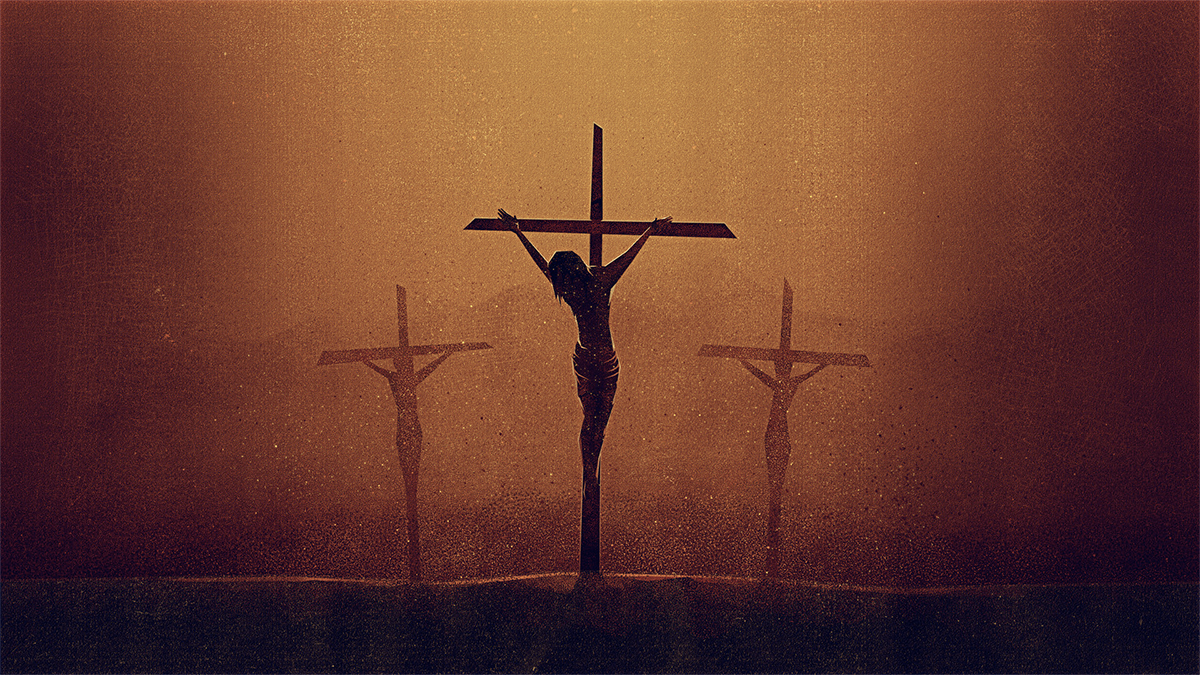

Another poet, Jill Peláez Baumgaertner, begins her poem with the death Jesus faced and his cry of dereliction, “My God, my God,”

His ragged cry, threads trailing,

a cry full of nails, rips, tears, tēars,

the cry spilling over the full cup

he has taken.

She describes his words as a cry of God to God. She calls it a dark work, undertaken on our behalf. It is part of Jesus’ work to those who have death within. The answer to his question is “the silence of the dirt scattered on the lowered coffin.”

Baumgaertner takes us to the mystery of the cross where God lives his own silence, God feels the grief of dying, God lives Jesus’ question, and experiences God’s absence. Such is God’s solidarity with us. This Good Friday is

a shattered

day left behind, then deep night

and sleep and only much later

the awakening to breath

and new light. But for now this

is the present through which

the future becomes the past.

We cling to his cry, our God,

who now knows what we know.

We are a people who know death is in us. We are also a people whose lives are embedded in the life of Christ, awakening to new breath and new life.

We are a people who know death is in us. We are also a people whose lives are embedded in the life of Christ, awakening to new breath and new life.

Rieux said the only way to fight the plague is with decency, which he defined as doing his job. Our job as those who live in Christ is to stand in solidarity with others, showing empathy for those who are ill and for those who make great sacrifice tending to the ill or working in essential jobs while fearing for their health.

The main work most of us have during this time is to distance ourselves physically from others. It does not seem like much, but it is not easy, and it is the loving thing to do. We can maintain physical distance while doubling our efforts to stay in contact with others to offer what Luther called “the mutual conversation and consolation of the people of God.”

Bruce K. Modahl

March 25, 2020

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community