“What I Learned from Ed Schroeder” (Part 2)

Co-Missioners,

Two weeks ago we sent you the first half of an extensive appreciation by Steven C. Kuhl of Ed Schroeder’s theological legacy. Steve presented this at a memorial event in St. Louis on June 1. Today we pass along the rest of what he said. See below.

On a related note, with bitter death and June 1 as the connection: we stumbled this week across a magnificent funeral sermon. The preacher was the ELCA’s Nadia Bolz-Weber, to some a scandal, to others a breath of fresh Lutheran air. The occasion was the funeral of her friend Rachel Held Evans, a young Christian thinker of sufficient prominence to land an obituary in The New York Times. The funeral happened on the same day we gathered in St. Louis to remember Ed. We think you’ll appreciate how Nadia—Pr. Bolz-Weber—bathes her hearers in the promise of Christ, using vivid, down-to-earth American English of the 21st century America to tell it like it is.

We think Ed would applaud too, thanking God as he did so.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossing Community

What I Learned from Ed Schroeder: A Historical-Theological Memoir

(Part Two)

By Steven C. Kuhl

Christian Ethics: What Does It Mean to Take the Holy Spirit Seriously

The issue of Christian ethics or “the third use of the law” is basically a debate about the final prognostic step (P-6) in the Crossings template. The complexity of the issue cannot be underestimated, to wit, the debate over the meaning of Article VI of the Formula of Concord. In a nutshell the issue is this: What is the role or function of the law of God in the life of the Christian. Everyone agrees that, because Christians are simultaneously sinners and saints, believers and unbelievers, the law has a first, “civic” function of restraining them as sinners and a second, “theological” function of exposing them as sinners. But does it also have a third, ethical function of “guiding” them even in so far as they are true saints, that is, true believers in Christ? In short, what guides the daily life of the Christian as a Christian? Is it the law or is it the Spirit?

Disagreement between the Elert-ians and the Missouri hierarchy couldn’t be more stark on this issue. The Elert-ians say it is the Spirit; the Missouri hierarchy says it is the law. The Elert-ians charge the Missouri hierarchy with legalism; the Missouri hierarchy charges the Elert-ians with antinomianism. The Elert-ians say the Missouri hierarchy doesn’t take seriously the Spirit’s animating power in the life of the believer; the Missouri hierarchy says that the Elert-ians do not take seriously enough the role of the law as an “eternal” expression of the will of God. How do we slice through this Gordian knot?

The chief problem, at least as I think I learned it from Ed, is that the proponents of the third use of the law fail to distinguish law and gospel as two contradictory words of God. They fail to see that the gospel is notmeant to be a word that complements or supplements the law, but one that contradicts it, that crosses it out! Stated differently, the law by definition is a word that always criticizes sinners, and ultimately criticizes them to death, period! In terms of ethics, it always says, to use Ed’s nickel words, “you got-to… or pay the consequences.” The Confessions expression for this is lex semper accusat, the law always accuses. The gospel, by contrast, is a word that always forgives sinners and ultimately, raises them up (after the law has mortified them) to new life, period! In terms of ethics, the gospel says “you get-to…because I am with you to will and to do.”

Therefore, the first question is “what does it mean to take the law seriously?” It means to never, ever backing off from its critical, deadly function by imagining it can be a friendly guide. In one Thursday Theology post Ed argued that it was not he who didn’t take the law seriously, but the third users. As a matter of fact, they were no better at taking it seriously than the antinomians. Why? Neither took the lex semper accusat character of law seriously. And so, to show what it meant to take that seriously he proposed his own “third use of the law” proposal. Note how this matches up with the diagnostic “D’s” in the Crossings Template. The first, civil use is to expose misbehavior (D-1), the second, theological use is to reveal the idolatrous heart (D-2), and the third use is to execute judgment (D-3). The one law of God carries out these three effects on sinners.

The second and, more important, question is, “What does it mean to take the Holy Spirit seriously?” For Christian ethics is about being led or guided by the Spirit as Paul makes unambiguously clear: “But if you are led by the Spirit, you are not subject to the law” (Gal. 5:18, NRSV).

What makes this question so challenging is the fact that we have no natural sense of the Holy Spirit as we do of the law. By God’s doing, fallen humanity’s psyche comes with a built-in antenna for the law and an inescapable sensitivity to criticism. Paul calls that accusing/excusing quality “the conscience” (Rom. 2:15), a term he borrowed from the philosophers before him who majored in studying and trying to understand (fallen) humanity.

By contrast, there is no such antenna for the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit always comes to the sinner as an intruder of sorts in conjunction with the proclaimed gospel, creating within a New Adam who, this side of the resurrection, is always engaged in mortal combat with the Old Adam. In this regard, we are reminded of the way the resurrected Jesus intruded into lives of the disciples on that first Easter to initiate in them the battle of faith and unfaith, sinner and saint. The anthropology of the Christian is therefore strange and mysterious. It has been variously described, by such Christian thinkers as Paul, St. Augustine, and Luther, as an inward battle between the flesh and the spirit, the old Adam and new Adam, the sinner and the saint-and as both an experiential description and theological conclusion.

Of central importance is the fact that the two Adams are polar opposites. The new Adam is marked by faith in Christ and is free from sin, the accusations of the law and death, waiting only for the final fulfillment. By contrast, the old Adam is marked by its rebellion against God and is in bondage to sin, death, and the accusations of the law, which also awaits fulfillment. Because these two opposite beings exist simultaneously in the one Christian person, we say that the Christian is simultaneously a rebellious sinner and believing saint and that the experience of being a Christian is a struggle for faith. In the Crossings template this is what the prognostic “P-5” is all about: the rise of faith in the gospel as the inward operation of the Holy Spirit.

But the Christian life is not only an inward experience, it is also very much an outward engagement with the world. Therefore, the question of Christian ethics emerges. In so far as the Christian is a sinner the two function of the law applies, just as they do to any unbeliever. God will use the law on them to restrain their misbehavior (D-1) and to expose their idolatry (D-2) and execute his judgment (D-3). But insofar as the Christian is a believing saint, the law no longer applies to her. That’s because Christ’s victory over sin, death and the law (P-4) has become hers by faith through the working of the Spirit (P-5) so that she now walks in love, guided by the Holy Spirit (P-6).

Of course, the question naturally arises, Wwhere does the content of Christian love come from?” How do we know what to do? The answer is deceptively simply. It comes out of the freedom of the gospel: freedom to assess the needs of those we meet in daily life (we call them neighbors) and to help them as we are able. Luther named his great treatise about what it means to be a Christian “The Freedom of a Christian” for a reason. For Christians, in so far as they are Christian, are little Christs whose actions are rooted notin the law (which moves us by poking us with sticks and dangling carrots before our eyes) but in Christ (who has already given us everything by faith).

To be sure, we should not think that everyone, all the time, will like the ethical freedom out of which the Christian lives. True, most of the time the Christian life will look quite conventional, especially, as Christians live out their freedom in their various worldly callings. But at times it may become unconventional, even counter-cultural in the eyes of some. One example of this in Ed Schroeder’s life is the positive assessment he made concerning homosexuality.

Ed was accused of antinomianism by numerous critics who assumed he came to this decision by simply disregarding the law as having any validity in the name of the gospel. Ed categorically denied that. While he did make his decision in the freedom of the gospel, the decision was actually based on his reassessment of past understandings of the law which said homosexuality was categorically sinful because it was “against nature.” Ed now thought that the scientific study of the creation and his encounter with gay Christians showed homosexuality to be a genuine orientation and thus part of God’s naturally ordering of creation. Just because homosexuality is a minority orientation does not mean that it is an illegitimate orientation.

Of course, just as heterosexuality can be sinned against, so can homosexuality. Therefore, the law in its civil function (which not only restrains sinners but does so with the purpose of protecting sinners from one another) must be fairly applied to homosexual relations as it is to heterosexual relations. In our present context what that fairness means for homosexuality is still being worked out and, as Ed also knew, Christians of good will might disagree in their assessment of these culturally challenging ethical issues. It generally takes time for these re-evaluations of the law to settle into the social fabric and sometimes laws get changed and sometimes they don’t. But as a theologian it was his job to help church and society to think about the ethical issues of the time. His contribution to that is clear: when considering how best to serve this old, conflicted creation of God’s, Christians need to both, properly distinguish between law and gospel and ground their discussion in an up-to-date theology of creation.

Enduring Legacy

As long as this retrospective on “what I learned from Ed” is, it is only the tip of the iceberg. But neither you nor I have the time or the stamina to say more at this time. So, let me close with a couple of thoughts on what might be called the legacy that Ed leaves us.

Number one, for me, is his image of the hermeneutical wheel for visualizing the theology of the Augsburg Confession, along with the book “Gift and Promise” that introduces it to the publishing world. At the hub is the gospel; it is the weight-bearing gift of God to sinners upon which everything turns. The rim represents the theological method that accompanies this gospel: the distinction of law and gospel. The gospel is ultimately about distinguishing God’s two words, law and gospel, and not simply God’s word from human words. To distinguish law and gospel is what it means to think with the gospel, and it is not something that only theologians do; every Christian does this as he or she encounters issues and questions of everyday life. Finally, the spokes of the wheel are articulations of the gospel with regard to specific issues that confront us. Doctrines and practices are appropriately understood and acted upon only when they are rooted in the gospel hub and held in place by the rim, the proper distinction of law and gospel.

The wheel reminds us that Christian teaching is not a list of isolated doctrines or practices that stand on their own and that have to be believed. Christian teaching is about showing how everything connects to the gospel. He was fond of saying that the Augsburg Confession gives us twenty-seven examples or case studies of issues that were pertinent to the Sixteen Century Reformers and that needed to be re-rooted in the gospel. They were called “articles” because they are all “articulations” of the gospel with regard to the topics in question, with article IV articulating the very nature of the gospel itself, thus, representing the hub: that we are justified before God by grace through faith in Jesus Christ.

But the wheel also reminds us that the job of articulating the gospel is never done. There is always room for more spokes to be added to the wheel because there will always be new issues that Christian people will need to think through. Therefore, the heart of systematic theology and Christian ethics is to help people think with and live in the gospel by helping them to distinguish law and gospel.

Number two, Ed was a Christian of his times. I don’t mean that as a limitation or weakness, but a strength. To be a Christian of one’s times means to engage—in freedom!—whatever God places before you in the moment, leaving the outcomes to God. In Ed’s case, this meant that, in the course of his life, some doors were opened to him and some doors were slammed in his face. Two doors that were opened to him are of particular note.

The first is the door that led to the co-founding of the Crossings Community with Bob Bertram. Although Crossings did not represent a new idea (the crossing of faith and daily life was always the main thing since Valpo days) it did give a new context for doing it, the everyday world of the laity. For Ed, that meant the closing of the door of teaching in a conventional seminary setting. That was especially hard for Ed because, in this case, that seminary door to be closed was not Concordia Seminary, but Concordia Seminary in Exile—Seminex. Ed was not ready for the door of Seminex to close. For as he saw it, Seminex still had a reason for being. For him, exile had given maturity to a theological insight that the Church needed but was not yet ready to receive. Therefore, exile still needed to be its home. Nevertheless, that would not be the case. Even so, as this door closed a new door opened called the Crossings Community. Of course, the outcome is clear. It’s us— this Crossings Community gathered to remember and give thanks to our departed brother and teacher Ed for teaching us the gospel in such a fresh and life-giving way.

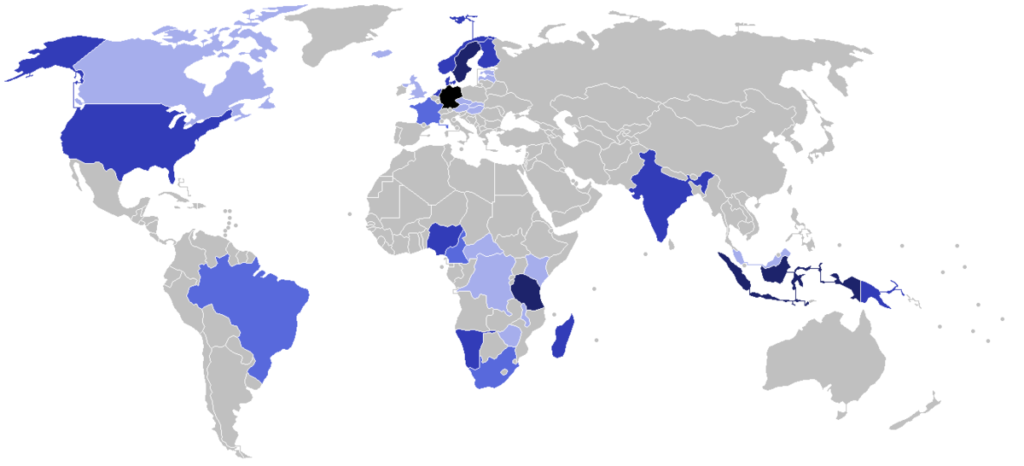

The second door that opened happened as Ed closed the door to Crossings, at least as its fulltime executive director. That door opened to the world. Using retirement as “freedom” to spread the gospel, Ed and Marie traveled around the world as missionaries, touching the lives of countless many with the good news of Jesus. Paul Tambyah, who is with us here from Singapore today, represents that opened door to the world. In addition, Ed also made on impact of the theology of mission, offering his gentle critique of the reigning “Missio Dei” theology with his “Promissio Dei” theology, one that conscientiously distinguished God’s two missions in the world of law and promise.

In the last analysis, for Ed and for the legacy of the gospel that he taught us, there is only one more thing to say: We have been edified and God has been gloried through his servant-child Edward H. Schroeder.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community