Biblical Depiction as Judgment and Promise

Co-Missioners,

“Christ for you, Christ for us.” Call this the bumper sticker version of God’s key message to the world, entrusted for delivery to folks strangely called “the saints,” the strangeness arising from the fact that no one save God would think to label them as such. How ordinary they look. How variegated too.

The Gospel reading for this coming Sunday—Luke’s account of Jesus’ crucifixion— will portray this core message in a word-picture for the ages. Assorted details make it plain that the Chosen One’s life is sacrificed for all.

But how will everyone grasp this? What else might it take for all to see that Christ died and was raised “for me,” to say nothing of my ilk? Such are the questions that lurk beneath the surface of today’s contribution. We thank Bruce Modahl for sending it along.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossing Community

Appropriating the Biblical Narrative

by Bruce Modahl

Cultural appropriation is generally considered inappropriate. A Christian pastor presiding at a Seder meal is as offensive to most Jews as a rabbi presiding at the Lord’s Supper would be to most Christians. American Indians, robbed of land and way of life, resent sweat-lodge tourists raiding also their spiritual heritage.

There is another kind of cultural appropriation we mostly applaud. That is works of art that depict the biblical narrative in contemporary and culturally-specific garb. Japanese artist Sadao Watanabe portrayed biblical subjects with Japanese features and in a Japanese context. The siege of Jericho, the Visitation, the Nativity, the adoration of the Magi, flight into Egypt, presentation in the temple, Sermon on the Mount, Last Supper, and much more are located in Japan in traditional Japanese dress. Christian artists from the sub-continent of India have done the same for their culture.

Just outside the door of my study I had two large prints of biblical scenes by the Flemish Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder. His focus on ordinary peasant life carried over to his religious paintings. The laborers and stonemasons in The Tower of Babel look as though they were recruited from the Dutch countryside. The Census at Bethlehem is filled with people at work and children playing in a Flemish village: a butcher slaughters a hog, children play on the ice and engage in a snowball fight, a man stands with a clapper in hand in front of a hut with a begging bowl. (He is warning of the presence of leprosy).

Just outside the door of my study I had two large prints of biblical scenes by the Flemish Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder. His focus on ordinary peasant life carried over to his religious paintings. The laborers and stonemasons in The Tower of Babel look as though they were recruited from the Dutch countryside. The Census at Bethlehem is filled with people at work and children playing in a Flemish village: a butcher slaughters a hog, children play on the ice and engage in a snowball fight, a man stands with a clapper in hand in front of a hut with a begging bowl. (He is warning of the presence of leprosy).

When children from our school came to my office, I delighted in showing them these pictures and relating the stories from the Bible. I asked them if they could find Mary and Joseph coming into Bethlehem to register for the census. It always took a while, for Mary and Joseph were but two of the ordinary folk in the painting. However, the children always found them eventually because Mary’s was the only donkey in the painting. They are headed toward the crowd gathered at a building that bears the double-eagle standard of the Hapsburgs, who ruled the Low Countries from Spain.

An artist from Central America rendered Jesus with the features of an indigenous person hanging on the cross surrounded by soldiers in the dress of that country’s army. St. Sabina Roman Catholic Church on the south side of Chicago in a predominantly African American neighborhood has a large portrait of the black Christ, reaching out with his scarred hands.

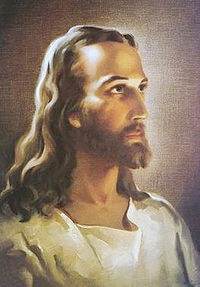

The Sunday school illustrations of Bible stories and the images of Jesus with which I grew up included an approximation of clothing worn in the ancient Near East. However, the faces bore little resemblance to the tour guide who led our church group on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He asked us if we wanted to know what Jesus looked like. “He looked like me,” he said. Our tour guide looked nothing like the noble man with the Roman nose in Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ or the young man with the boyish grin in more contemporary renderings. Our culture may not portray him as a blond Aryan, but it certainly does not make him look like a Semitic native of the land.

The Sunday school illustrations of Bible stories and the images of Jesus with which I grew up included an approximation of clothing worn in the ancient Near East. However, the faces bore little resemblance to the tour guide who led our church group on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He asked us if we wanted to know what Jesus looked like. “He looked like me,” he said. Our tour guide looked nothing like the noble man with the Roman nose in Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ or the young man with the boyish grin in more contemporary renderings. Our culture may not portray him as a blond Aryan, but it certainly does not make him look like a Semitic native of the land.

Relocating the biblical narrative can make people uncomfortable. Joel Sheesley locates the sacred story in contemporary suburban settings. In Lot’s Distress he paints Lot dressed in swimming trunks, in a lounge chair poolside, while his children are at play in the pool with an inflatable orca whale. The distress shows in the expression on his face. Lot’s Wifeis another painting in the series. She is a soccer mom in a summer dress, standing on the edge of the playing field with a cooler at her feet. Gaze at her sunglasses and the viewer realizes she is seeing raging fire. After a showing of Sheesley’s art, members of a congregation purchased Lot’s Wife for the church’s collection. The reaction to the painting was widely negative. Someone mocked the painting by identifying a member of the congregation who resembled the woman in the painting. Nervous laughter relegated the painting to a wall in the basement. People could not fathom God’s judgment on a scene that looked like a vignette from their own lives.

The discomfort at Sheesley’s work pales in comparison to the discomfort stirred by British artist Edwina Sandys who sculpted Christa in cruciform pose and with bare breasts. She created it, she said, to portray the suffering of women. It was hung not in a museum or gallery but in a devotional space at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. The bishop was furious. The reaction was aggressive. The sculpture was quickly packed up and shipped back to the artist. Thirty years later it was brought back to the cathedral as part of an art exhibit titled “The Christa Project: Manifesting Divine Bodies.”

The discomfort at Sheesley’s work pales in comparison to the discomfort stirred by British artist Edwina Sandys who sculpted Christa in cruciform pose and with bare breasts. She created it, she said, to portray the suffering of women. It was hung not in a museum or gallery but in a devotional space at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. The bishop was furious. The reaction was aggressive. The sculpture was quickly packed up and shipped back to the artist. Thirty years later it was brought back to the cathedral as part of an art exhibit titled “The Christa Project: Manifesting Divine Bodies.”

Most discomfiting of all was the art witnessed by a young American theology student at Tübingen in the early 1950s. He made a practice of visiting the churches in the hillside villages surrounding the city for worship on Sunday mornings. He walked into one such church and was shocked to see the artwork hanging above the altar. It was a rendering of Christ stepping from the tomb, a typical subject matter for an altar piece. However, the Christ stepping from the tomb was the same blond and blue-eyed Aryan youth of Nazi propaganda.

As startling as these last two examples are, all of them bear political, social, and theological implications. For people far removed from the biblical narrative and culture, Watanabe’s prints and the Black Christ convey “Jesus is also for me and the biblical story is my story.”

Problems with the images of Jesus with which I grew up are signaled by a question commonly asked of Google: “Is Sallman’s head of Christ an actual portrait?” We assume Jesus looked like us. With that comes a goodly amount of condescension toward Christians from other parts of the world. Such condescension comes from conservative and liberal voices.

Bruegel equated the Roman Empire occupying Judea with the Hapsburg rule of the Low Countries by placing the Hapsburg standard on the government building. Brueghel faced political repercussions for some of his art. The Central American artist aims a more pointed critique at repressive government while also appropriating Jesus’ suffering on behalf of the suffering of indigenous people at the hand of the government.

I think we can agree that Sandys’s Christa does not belong in a devotional space, and portraying Jesus as the youth of Nazi propaganda is reprehensible. But rather than responding viscerally to religious art, is there a framework we can use to guide our appreciation and understanding? I propose we use the same method we employ with Scripture. Scripture speaks God’s word of judgment and promise. What do we see of these two in a work of art? The judgment may be against those who oppress, but judgment also points back at us. Do we lodge our trust in something other than God’s promises and in someone other than Jesus as we face oppression? The main focus of Scripture is on Jesus, God’s promise-bearer and -fulfiller. How does a work of art direct us to him? For those familiar with the Crossings format, we might even bring to bear the language of diagnosis and prognosis. In what ways does the work of art diagnose our maladies? Does it offer us a new and hopeful prognosis in Jesus?

I have hanging in my study a print of sinking Peter being rescued by Jesus. The depiction by Scottish artist Peter Howson is unlike any I have seen. The boat looks to be hopelessly swamped. Jesus appears in the middle of a dark scene, illuminated, dressed in white, dazzling. The artist gives us a foresight of resurrection. Jesus is dragging Peter back to the boat as some of Peter’s friends reach out to help him. There is judgment for those who have stepped out with all confidence in ourselves, only to sink. There is comfort in Jesus’ grip and the outstretched arms of friends.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.