Ten “Promising” Words? An Interchange (Part 1)

Co-missioners,

Last month we sent you a two-part posting of an essay by Paul Jaster entitled “God’s Ten Promising Words.” It prompted an interchange that we share with you this week and next. Our editor, Jerry Burce, provides a brief introduction.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

________________________________________________________________

Ten “Promising” Words? An Interchange between Michael Hoy and Paul Jaster

Introduction

Lutherans started arguing in the 1530’s about the role the Law of God plays in the lives of Christian people. They’ve been at it ever since. The matter has surfaced more than once in the brief life of our own Crossings Community. Two concerns keep recurring in the argument. One is to give the Law its proper due as the Word of God, addressed as much to baptized people as to anyone else. The other is to keep it from encroaching on the Gospel, that greater and alternative Word of God on which our hearts, hopes and lives need to be anchored.

This noted, I’m not surprised that Paul Jaster’s essay, “God’s Ten Promising Words,” provoked some quick response when we published it last month. I guessed then that his use of the word “promise” in connection with the Ten Commandments might scrape on sensitivities. Readers steeped in the old argument could well hear him fudging the distinction between Law and Gospel. As it happened, some did.

One of them, Michael Hoy, sent me a note about this. Mike is a former president of the Crossings board and the editor of two posthumously published books by Robert Bertram. I passed Mike’s note along to Paul. Paul wrote to Mike. Mike in turn wrote directly to Paul. I got in touch with both of them and secured their permission to share the substance of their back-and-forth. My heartfelt thanks to them for letting me do this. Readers less familiar with intra-Lutheran debates about Law and Gospel will learn much from their discussion.

As with Paul’s initial essay, this too will reach you in two parts, each of a digestible length in keeping with our current editorial policy.

A final note: I was struck as I read by the graciousness with which Paul and Mike address each other. It will strike you too, I trust, especially next week. Join me in applauding it. Better still, thank God for it. Gracious dispute is all too rare among Lutherans, as lots of us have noticed to our sorrow these past many years.

—JEB

+ + +

The Starting Point—

Read or review “God’s Ten Promising Words” by Paul Jaster—

• Part 1 published on April 13

• Part 2 published on April 20

+ + +

Michael Hoy’s Initial Comment to the Editor—

I have read through this essay a couple of times, and still find myself head-scratching over how Paul is seeking to turn the Ten Commandments into something that are not only “words,” but “promising words.” His preference to call these the Ten “Words” is OK, but it doesn’t change the point—for the Law of Moses is a word, though surely not ultimate for our sake, lest we deny the faith we surely “trust.”

Still, in the second part of the essay, Paul employs a phrase that is also a head-scratcher: “It takes a lot of faith in the crucified and risen Jesus….” As far as I know, Jesus never seemed to like the idea of measuring faith quantitatively, only qualitatively— i.e., trusting Him as the Source and Power that makes our faith great (cf. Luke 17:1-6). This faith trusts Christ in spite of the fact that, as Luther said in concluding his commentary on the commandments in the Large Catechism [LC], “This commandment [word] remains, like all the rest, one that constantly accuses us, and shows us how upright we really are [or are not] in God’s sight.” (LC I:310) How then does Paul still want to call these commandment-words “promising”?

Bob Bertram always discussed the commandments in conjunction with the first article of the Creed. Here he followed Luther, who, in the Small Catechism [SC], concluded his explanation: “For all of this I owe it (schüldig bin) to God to thank and praise, serve and obey him. This is most certainly true.” (SC II:2). In the LC he connects this schüldig bin to the Ten Commandments (LC II:19). How are we doing with that debt?

While I have used the Nestingen and Forde commentary for confirmation in the past, I always expounded on how we are freed from the debt by our faith in the promise—not in these words of Moses, but in the promise of the crucified and risen Christ. Their approach tended to side more with Karl Barth on how theology is about God, while Bertram accented how theology is about us, through faith in Christ.

There is nothing in Paul’s commentary that speaks at all about how these “words” are actually accusatory, save only from his citations of Wedel and Luther. A few years ago, in 2020, I published a series of ten sermons on the ten commandments (words) that preserved their accusatory function but also the promise that we have in Christ. We live by that Promise, not by the “words” of Moses.

+ + +

Jaster’s First Reply to Hoy—

1. Thank you, Michael, for your questions. You honor me by considering my article worthy of your attention and reply.

2. “A theologian of the cross calls the thing what is,” says Martin Luther in his Heidelberg Disputation, Thesis #21, May 1518.

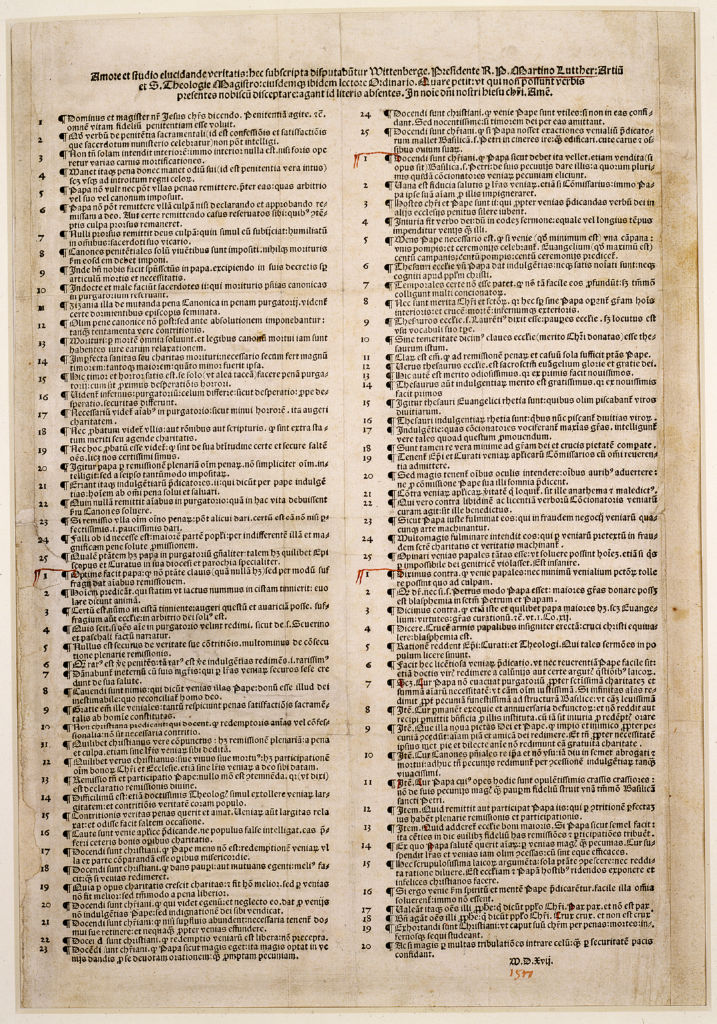

3. Six months earlier, on October 31, 1517, Luther had sparked a Reformation and a printing press cottage industry by correctly translating one word. He did this in the first of his 95 Theses. Following the lead of Erasmus, he read the Greek metanoia of Matthew 4:17 as referring not to the late medieval Sacrament of Penance, but to the lifelong habit of “repentance.” Jesus, Luther said, willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance. Thesis One!

4. My point here is that correctly translating one Bible word can make a heap of difference. The existence of the Lutheran Church is proof of that.

5. It is not my “preference” to call the Ten Commandments the “Ten Words.” It is the choice of the Hebrew Scriptures to call them the ten words (debar). This is evident in the New Revised Standard Version. See the footnote at Deut. 4:13. See also Patrick D. Miller, The Ten Commandments, page 15.

6. I think it would be a great service to our Jewish brothers and sisters to observe there is a difference between the Hebrew words debar (word) and mitzvot (commandments). But more than that, I think we are missing something about our own promising theology when we fail to observe the difference. There is rich ore to be mined in this difference between commandments and words when speaking of the 10. Why limit ourselves to “commandments” when the “words” imply promises?

7. But first, what is the “law of Moses”—a term you use in your first paragraph? It is certainly not all Ten Commandments. Of these, four through ten are pieces of international law that preceded Israel in the Ancient Near East. See the Code of Hammurabi.

8. Or is it perhaps the 612 mitzvot counted by the rabbis in the Hebrew Scriptures? But they preferred the term “Torah,” teaching. Thus, I personally always speak of the Torah and not “law of Moses.” For me it is a matter of respect to our Jewish brothers and sisters.

9. In the historical Lutheran writings, Luther and others contrast the way of Moses (law) versus the way of Christ (trusting in God’s promises in Christ and the benefits he brings). For shorthand, they contrast “Moses” versus “Christ.” I consider that still a valid way for Lutherans to talk among themselves today, but it is somewhat in-house language and not always the best for public witness.

10. The way of Moses is covenantal fidelity as described in the Torah, the prophets, and the writings, plus oral tradition as interpreted by the rabbis through the ages—including, in my book, Rabbi Jesus. (I am a Bruce Chilton fan.) The way of Christ is faith in God’s promises in Christ and the benefits he brings.

11. The Ten Words ARE “ultimate for our sake” as understood in Lutheran theology. Why else did Luther include them in the Small and Large Catechisms?

12. The use of the words “fear” and “love” before each of Luther’s explanations to the Ten Commandments is due to a debate between Philip Melanchthon and John Agricola over how faith is born in a person. Melanchthon argued that faith was born out of the fear of God’s wrath. Agricola argued that faith was born out of a childlike love in response to the love of God. This led to a bitter debate. Luther intervened and ordered a truce. He adopted both positions combined, fear and love.

13. Luther used the word “trust” only for his explanation of the First Commandment. As I state in my article, I wish he had used it for all ten. I think “trust” is the key word for us today.

14. I find it odd for you to say, “Jesus never seemed to like the idea of measuring faith quantitatively, only qualitatively.” As I recall, Jesus said that a mustard-seed size of faith is enough to move mountains and plant them in the deadly, raging, saltwater Sea, Tiamat, the ancient foe of the Ancient Near East, the sea dragon of scriptures. In an apocalyptic understanding, this means “to tell the mountains to do their eschatological thing.” In other words, just a mustard-seed size of faith is enough to bring on the beginning of the new age. See Matthew 17:20, Luke 17:6.

15. So, for me personally, anything after the first of mustard seed size of faith is extra gratis, if there is such a thing. I define Lutherans as “those who extol faith in God’s promises in Christ.” I think we really need to hit hard that word “extol.”

16. Where I get that from is the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, IV, 48-60, the section on “What Is Justifying Faith?” In that section, Melanchthon says that “faith is worship!” And not just any worship, but that worship which pleases God the most and receives the benefits of Christ contained in God’s word of promise. And then that section contains a long list of the benefits of Christ received through faith alone.

17. Call me crazy, but I consider even that word from God that “accuses us” as promising. I see law and promise as two sides of the same coin. The Law tells us of our need for God’s promises in Christ. The Gospel tells us of the promising Christ we need, as opposed to Jesus as only a model or example.

18. For reasons that will be discussed in a forthcoming article on Apology IV, I would prefer to translate Luther’s conclusion to the First Article of the Apostles’ Creed as “For all this I am bound to thank and praise, serve and obey God. This is most certainly true.” (SC II.2). As Forde and Nestingen point out in Free To Be, this is as opposed to groveling. Your use of the word “owe” sounds to me a bit like groveling. In my experience with children, the debt we cannot pay back is better addressed in the Second Article of the Apostles’ Creed.

19. I have used Free To Be as the basis for confirmation for over 45 years. I disagree entirely with the assessment that its theology is not also “about us, through faith in Christ.” I could not disagree more on this point.

20. Though perhaps I do see something missing in Free To Be’s treatment of the Ten Commandments, and have compensated for it in my own teaching and use of these materials. What I have found lacking is articulated Part Three of my essay.

21. Michael, you are in a better position than I am to judge how this relates to Barth. I know nothing of Barth. I have my hands full enough with Luther.

22. In my piece on the Ten Words, my citations from Wedel and Luther ARE what I have to say about what is so accusatory. I did not go into greater detail because of Thursday Theology’s length restraints. I also assumed that anyone reading this piece would already know how the Ten Commandments accuse us. In any case, a forthcoming article on Apology IV will go into great detail about how the law accuses us.

23. My wife Laurie is also a pastor. We talk about the law’s accusation all the time in confirmation classes. How we always have other gods, things to which our hearts cling. How we take God’s name in vain and use it as a curse word or piece of punctuation. Or how we fail to take one hour out of the 168 hours given every week to rest in God’s Word and gladly learn it. How we fail to honor our parents even when they are abusive and how we fail to honor their representatives. How we kill all the time with just a word, a cruel careless word. How having sex outside marriage has a price tag. How we steal, especially by not paying a fair wage for the fair day’s work. How important reputations are and how we can destroy them with a word of gossip. And how there is a multibillion-dollar industry that is designed to make us covet wisdom leads to the breaking of the first commandment. The advertising industry and the danger of false promises.

24. I did not think it necessary to point all this out to the Crossings’ audience; but apparently, I should have, and now would if I were I to rewrite the article.

25. However, today, it is more important to emphasize the obstacles to trusting in the promises implied in the Ten Words, which is my emphasis in Part Three, and the main point of the article. Thus, my use of “it takes a lot of faith.” And for me, justifying faith is always in the crucified and risen Christ as opposed to a Jesus that is a new and better Moses, an example for God pleasing behavior.

26. I do not think there is a “third use” of the Law. If there is, it is to say that the first use, civil discipline, still applies to Christians after regeneration.

27. Thanks, Michael, for your questions, which allow me to clarify my thinking for the Crossing’s audience.

+ + +

—to be continued next week with a reply from Hoy to Jaster

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community