A Scholar’s Update

Co-missioners,

Dare we call him a Crossings scholar?

The church historian Kurt K. Hendel launched his teaching career in 1973 at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, and joined Christ Seminary—Seminex in February, 1974. When that school dissolved in 1983, he was among the majority of faculty members who found a new teaching home at the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago. He has been there ever since, doing all he can to ensure that Reformation theology gets the attention it deserves at a Lutheran seminary. His current title there is Bernard, Fischer, Westberg Distinguished Ministry Professor Emeritus of Reformation History.

Kurt has kept an eye on Crossings over the years, chipping in now and then with useful and encouraging comments along the way. This year he contributed two pieces to Thursday Theology. The first was a reprint of an article originally published in Currents in Theology and Mission. It used Luther’s own theology to reexamine the question of whether there is salvation to be had outside the church. This was followed a few months later by an assessment of Luther’s terrible late-life diatribe, “On the Jews.”

We have since asked Kurt to let us know what he’s been working on of late and where his interests might lie as he looks ahead to another year of scholarly pursuits. He got back to us quickly on this. We’re delighted to pass along his report this week. Let it prompt you to keep your eye on him as 2023 unfolds—or better still, to thank God for yet another skilled and well-placed servant of the Gospel who will spend the year touting Christ and his benefits for the world we’re stepping into all over again on January 1st.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

Recent Research Interests and Projects

by Kurt K. Hendel

While my scholarly vocation is that of a church historian, my teaching and publications have focused both on church history and on Lutheran theology. The Lutheran Reformation, Martin Luther’s theological perspectives, the theology of the Lutheran Confessions, and the reforming work and theology of Johannes Bugenhagen have been of particular interest to me and have, therefore, captured my primary scholarly attention. That continues to be the case.

Specific invitations to pursue particular scholarly projects have resulted in four recent publications. Two of those invitations came from Paul Rorem, the editor of Lutheran Quarterly. This fine theological journal continues to publish articles related to the quincentennial celebration of the Reformation. Each article examines a specific event or a publication that significantly shaped the Lutheran reform movement and its theology. My two contributions to this series addressed the Leipzig Debate of 1519 and Luther’s To the Christian Nobility, which was one of several seminal publications by the Reformer in 1520.

The Leipzig Debate marks a crucial moment in the early history of the Lutheran Reformation. The chief debaters were Luther and Johannes Eck, who would become Luther’s most ardent critic in the German territories. The two men addressed theological themes that highlighted the substantial differences between the emerging evangelical theology of Luther and the theology of the Roman Church. Nature and grace, the bondage or freedom of the will, the motivation and purpose of good works, the penitential theology and practices of the church, the authority of Scripture and tradition, and papal power were all explored during the debate. The role and authority of the papacy in the life of the church was a particularly volatile issue, and Eck focused especially on it as he insisted that Luther’s positions mirrored those of Jan Hus and were, therefore, heretical. The charge of heresy against Luther gained significant momentum after Leipzig and eventually led to the papal bull of excommunication and the imperial Edict of Worms. In spite of these developments, the debate also strengthened Luther’s resolve to foster the reformation of the church and its teachings and practices in light of the gospel.

Luther, therefore, continued to articulate his theology in numerous publications. Luther wrote his To the Christian Nobility because he was eager to articulate the implications of his theology for the reform of society, as well as for the reformation of the church. The treatise consists of three parts. In the first section, Luther explicates his understandings of the universal priesthood of the baptized, of good order in the church, and of the doctrine of vocation. The second section addresses three ecclesiastical abuses, namely, the avarice of the papacy, the continuing proliferation of the number of cardinals, and the expansion of the curia, all of which drained the fiscal resources of the church’s members. He also urged the calling of a council in order to remedy these challenges. The third section consists of a list of twenty-seven reform proposals that addressed problems in the church and the society in general. Luther’s articulation of the universal priesthood of the baptized and its implications for ecclesiology and the Christian’s vocation remain the most relevant contribution of this treatise, although his willingness to identify and offer solutions to significant ecclesiastical and societal challenges also remains an admirable example for contemporary Christians. The treatise thus continues to serve as a powerful reminder to the church that it must be cognizant of its own failures, of its need to be a reformed and reforming community, and of its calling to be God’s agent of transformation and justice in the world.

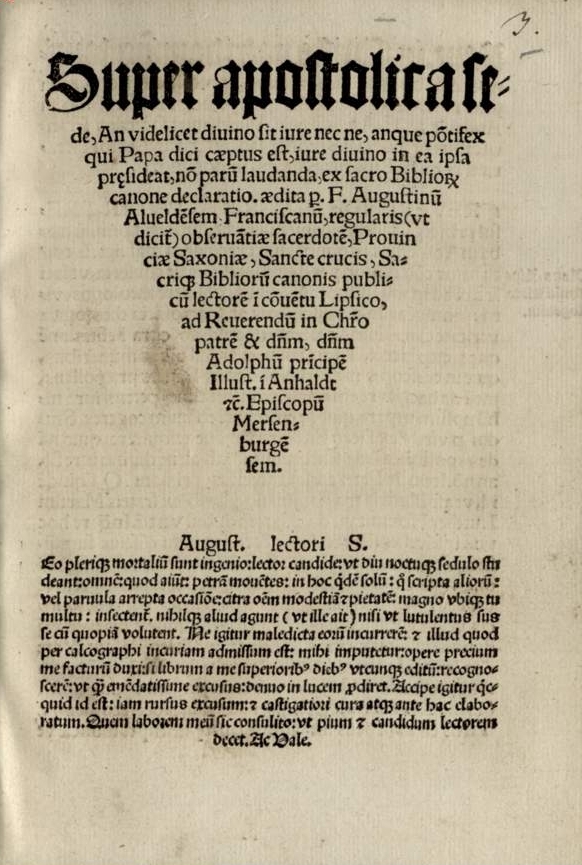

My other two recent publications are translations of original works in German. The first was written in 1520 by an opponent of Luther named Augustine von Alveldt. The original document is part of the Richard C. Kessler Reformation Collection, housed in the Pitts Theology Library at Emory University. The Collection consists of more than 3900 original manuscripts and printed works written by Martin Luther and contemporaries who supported or challenged the Lutheran reform movement. It includes more than 1000 Luther publications and thus constitutes the largest collection of original Luther sources in the U.S. I was invited to translate and annotate the work by Alveldt, the title of which is simply Ein Sermon.

Title page from Augustin von Alveldt’s “Schrift Super Apostolica Sede” 1520 ( Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, PD-Art; PD-old-100)

Alveldt was a friar who lectured on Scripture in the Franciscan cloister in Leipzig. He also served as provincial head of the Franciscan Order in Saxony. He was impacted by Renaissance humanism and its ad fontes emphasis and was an able Latinist and a student of the biblical languages. Alveldt became an early literary opponent of Luther and a diligent apologist of Rome. He particularly defended papal authority in light of Luther’s critique. He also supported the church’s Eucharistic theology and its sacramental practices and piety in response to Luther’s criticisms. Penance, ecclesiology, Mariology, and marriage and celibacy were additional topics of interest to Alveldt.

The ”sermon” is actually not a sermon but a short treatise. It consists of three sections. The first part serves as a self-defense against Luther’s ad hominem attacks on Alveldt in a recent publication of his. In the second section, Alveldt accuses Luther of heresy by linking the Reformer’s teachings to John Wyclif and Jan Hus. The third section summarizes Alveldt’s defense of papal authority. The friar agrees with Luther that Christ is the Head of the church. However, Christ has also chosen Peter and his successors to serve as Christ’s vicars who are called to feed and nourish Christ’s sheep. The papacy is, therefore, divinely instituted and necessary for the well-being of the church because the pope interprets Scripture faithfully and guards the church against heresy.

If all this piques your curiosity, you can now read A Sermon online.

The second translation is of a 21st century work by Helmut Hartmann, a Lutheran pastor and superintendent in the former German Democratic Republic. He prepared a memoir of his life and ministry as a gift to his family on his seventieth birthday. The volume consists of a series of remembrances and reflections, one for each year of his life. While it is obviously personal in nature, the memoir provides keen insights into the challenges and opportunities that individual Christians, pastoral leaders, and the institutional church faced in East Germany. The persistent challenge of negotiating with those in power without compromising both one’s faith and one’s ethics is a consistent theme throughout this volume. Triumphs and failures are named with gratitude or with regret.

All told, the memoir is a fascinating, informative, and perceptive commentary on the individual believer’s and the church’s mission in a sociopolitical context that was intentionally antagonistic to the institutional Christian church and its members as they sought to remain faithful to Christ, to fulfill their vocation as Christ’s witnesses, and to serve as God’s agents of grace and love in the world. Because Hartmann refers to numerous individuals, places, and events in his memoir, the translation also includes copious annotations which provide necessary contextual information. The English title of the book is The Quest for Faithfulness. You can find it at Amazon.

All told, the memoir is a fascinating, informative, and perceptive commentary on the individual believer’s and the church’s mission in a sociopolitical context that was intentionally antagonistic to the institutional Christian church and its members as they sought to remain faithful to Christ, to fulfill their vocation as Christ’s witnesses, and to serve as God’s agents of grace and love in the world. Because Hartmann refers to numerous individuals, places, and events in his memoir, the translation also includes copious annotations which provide necessary contextual information. The English title of the book is The Quest for Faithfulness. You can find it at Amazon.

As to my scholarly research:

I have had the joy and privilege of continuing to teach at LSTC as an emeritus faculty colleague. Accordingly, much of my research and writing continues to be related to the courses I have been offering. Invitations to lead adult forum sessions or to present individual lectures in congregations have also inspired research and writing. The seminary and congregational lectures and presentations have not been prepared with the goal of publishing them, although I may offer at least some of these written materials to journals for their consideration. A significant part of this research and writing has been focused on current justice issues and commitments. This is due largely to the emphasis placed on the public church and the quest for justice in both the seminary’s curriculum and the ELCA’s current understanding of mission. My own theological and ethical interests are involved here as well. Martin Luther’s writings and Lutheran confessional theology have continued to remain primary resources for me as I address these matters.

Here are some topics that have been of particular interest to me:

- The care of creation

- Church and state relationships, particularly in light of contemporary religious nationalism—Christian nationalism, to be specific

- The Christian response to poverty

- Responsible Christian behavior during a time of pandemic

- War and peace

- Racism, and especially antisemitism

Here are some theological resources I have found both relevant and helpful in addressing contemporary justice issues:

- The doctrines of creation and incarnation

- Lutheran sacramental theology, especially in its insistence that the finite is a vehicle of the divine

- Luther’s two governances theory (aka the doctrine of the two kingdoms)

- Luther’s affirmation of the orders of creation

- The biblical and Lutheran ethic of faith active in love

- Luther’s emphasis that Christians have been freed to be servants of their neighbors

- The Lutheran doctrine of vocation

- The Reformer’s assertion that the only war Christians may support is a defensive war

- His insistence that the use of force and violence is neither justifiable nor effective in matters of faith and conscience

I commend all of these both to individual Christians and to the wider Christian community as they wrestle with the issues of the day. They have certainly been of use in my own research, writing, teaching, and witness.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community