Revisiting Patriotism

Co-missioners,

Noticing that America’s July 4th super-holiday falls on a Sunday this year, Matt Metevelis was moved to nudge us—his fellow preachers in particular—into some better and deeper thinking about the idea of patriotism. We’re pleased to share his argument with you.

Matt has had a busy couple of weeks, by the way. On June 24 Mockingbird published his second contribution to their website. It’s about funerals. If the current fascination with “celebrations of life” has chafed on you too, you’ll want to check this out: “Funeral Failures and Graces.”

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

On Vines and Fig Trees:

Neighbor and Nation in the Christian Life

by Matthew Metevelis

Congress had adjourned in the newly minted national capitol of New York City. Three public figures, representing the new federal government, took a belated trip from New York harbor to the crowded wharf of Newport, Rhode Island. They did this as a gesture of good will. In May of 1790 Rhode Island had finally ratified the constitution. The travelers intended to extend a welcome to one of the newer members of the union. They were high ranking figures. George Clinton was the governor of New York. The lanky Virginian Thomas Jefferson was now serving as Secretary of State. And his fellow Virginian George Washington was halfway through his first term as President of the United States.

Like local politicians who cluster around the tarmac when Air Force One lands today, the Newport dignitaries gathered on August 18, the day after the travelers arrived, to offer an official welcome to the leader of the country and the hero of the revolution. They represented various communities around the city. One of them, Moses Seixas, a warden of the Touro synagogue, captured Washington’s attention with a statement that cloaked a bold appeal under words of praise.

“Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People—a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship.” [1]

Liberty of conscience remained a critical social belief in Rhode Island, a colony which had been founded by Roger Williams, a dissenter from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. But for Newport’s citizens of Jewish faith and practice this was a personal matter. The horrendous record of European governments against Jews was well known. At one point Jews had been expelled from England until Cromwell welcomed them back. But in many places and even in the colonies their rights had been circumscribed, and even in places filled with other religious dissenters they had remained suspect. Even though many Jews had served in the revolution at great personal sacrifice, their neighbors still regarded them with fear. And since at this point the first amendment had yet to be drafted and ratified, this community had every reason to be apprehensive that the new government would not be one “which to bigotry gives no sanction, and to persecution no assistance.”

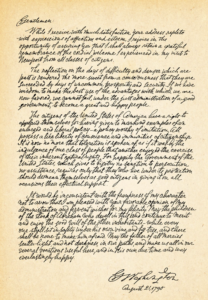

Washington heard these concerns loudly and clearly. Responses to such official welcomes were rare. But Washington felt compelled and possibly a little inspired to offer words of reassurance. Writing back on August 21st he addressed the entire synagogue:

Washington heard these concerns loudly and clearly. Responses to such official welcomes were rare. But Washington felt compelled and possibly a little inspired to offer words of reassurance. Writing back on August 21st he addressed the entire synagogue:

“The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

These words offered a watershed moment in human history. Toleration was a much-discussed policy throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. John Locke wrote a famous treatise about it. The basic idea of toleration was that certain suspect classes of individuals should have certain spheres in which they could live and participate in society in a limited sense. Most debates centered on what classes might deserve these considerations, but rarely did these discussions imagine granting the full rights of citizens to marginalized groups. According to Washington simple toleration fell short of the aims of the new government. All citizens had rights. All possessed in equal measure “liberty of conscience” and “immunities of citizenship.” The question no longer revolved around which groups could be suffered in the civic space but how different groups should interact together.

Washington assured the members of the Newport synagogue that the government “requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens.” [2] The criteria of who belonged to the body politic now centered not on what group they belonged to, what confession they adhered to, or what rank they held but only on their conduct as citizens. For Washington, this concept of citizenship contained so much more than just claims of status. Citizens were included in terms of their responsibilities and obligations. To drive this home Washington concluded with a prayer:

“May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light and not darkness in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.”

The quote about “sitting in safety under his own vine and fig tree” made it often into Washington’s speeches and correspondence. He even sings it in Lin Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton. It originally comes from Micah 4:4 in a series of prophecies about the rebuilding of Zion and the coming of peace to all nations. For Washington these verses pointed to what the liberty he had fought for and defended meant. First, it meant a freedom from outside interference combined with peace and security. Second, it meant conditions in which people could do their work and be fruitful, helping and lifting up others. Washington underscored this second aspect of liberty in his closing hope that God would “make us all in our several vocations useful here.” The citizens of Newport were free not only from state sanctioned discrimination, pogroms, expulsion, and interference in their way of life. They were also free to use their gifts and skills to bless their neighbor. The federal government would suppress all attempts at bigotry and persecution to allow the members of the Newport synagogue to flourish and contribute to the flourishing of their neighbors.

The quote about “sitting in safety under his own vine and fig tree” made it often into Washington’s speeches and correspondence. He even sings it in Lin Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton. It originally comes from Micah 4:4 in a series of prophecies about the rebuilding of Zion and the coming of peace to all nations. For Washington these verses pointed to what the liberty he had fought for and defended meant. First, it meant a freedom from outside interference combined with peace and security. Second, it meant conditions in which people could do their work and be fruitful, helping and lifting up others. Washington underscored this second aspect of liberty in his closing hope that God would “make us all in our several vocations useful here.” The citizens of Newport were free not only from state sanctioned discrimination, pogroms, expulsion, and interference in their way of life. They were also free to use their gifts and skills to bless their neighbor. The federal government would suppress all attempts at bigotry and persecution to allow the members of the Newport synagogue to flourish and contribute to the flourishing of their neighbors.

Modern discussions about American liberty seldom appeal to both aspects that Washington lifts up in this letter. Liberty gets reduced to “non-interference” or the right to act with as few constraints upon you as possible. The right presents this kind of liberty as sacred and inviolable while on the left it is castigated as a liability that permits injustice. Little discourse attends to the ideas of community and duty that animated many of the founders.

The American Revolution is not the amalgamation of a bunch of slogans painted on the self-assertive war cries of armed farmers as the Mel Gibson version would have you believe. Both in their writings and in their lives, many of the shapers of the American Revolution thought of the individual as deeply embedded in communities with responsibilities to neighbors. Franklin gathered fellow entrepreneurs together to found what today we would call “non-profit organizations.” The society of colonial Boston was an amalgam of neighborly bonds cemented in written covenants. The issue with much of parliamentary activity after the Seven Years’ War involved levying taxes without the kind of deferential appeals to colonial assemblies that Pitt the Elder regularly made in respect to their dignity. The revolution was fought less by William Wallace-style agitators (though these did exist) and more by town councils and civic militias where traditions of neighbors supporting neighbors for self-defense reached back centuries in the old world. [3] Citizenship in the new nation meant community. The ideal of the government was to absent itself from the everyday interactions of people as much as possible in order that neighbors might serve neighbors.

This more robust vision for American liberty might have more to recommend itself to professing Christians who are called to care for our neighbors and especially for those who are most in need. The irony of professing Christians waving the Gadsden flag that says “Don’t Tread On Me” when they follow a savior who was notoriously and graphically trodden upon is always amusing. Much better to the Christian ear is Washington asserting a government which does not entertain bigotry and allows for people to be neighbors to one another. I don’t have to worry if my religion would prevent me from voting for the best person to serve my community, or fuss over which people might deserve my support or not based on factors they can’t control, and least of all whether I can enter a good faith contract with someone I trust or not. Nobody is telling me who my neighbors are. No government can step in between me and my neighbor in need. I can help the man bleeding on the side of the road even if he is a Samaritan. Liberty means using my gifts as needs dictate I should. Liberty means that I am governed most proximately by the people who are near me and need me.

Through liberty properly understood and executed, the first use of the law is allowed to flourish. The government allows this by restraining and removing from the equation those who cause harm and by providing a forum where people can come together and do good on a massive scale (even if just how this is done is a subject of debate). All this is a function of God’s law as the sphere in which government exists. Lutherans might call it the “left-hand kingdom” where God governs by just rules and allows human beings to flourish.

Problems ensue when government crosses over from the law and becomes proclaimed as gospel. And this has been the default position in most of human history. Ancient emperors fashioned themselves as gods and many had cults that existed after their death. Martial glory and territorial conquest were the defining characteristics of many governments during the era of the divine right of kings. Communist governments presented themselves as historic processes working themselves out to create utopia. “Christian nationalism” is the form that this tendency has taken on our own soil. The idea that America was founded for some divine purpose which gets revealed in subsequent ages awaiting a crowning eschatological glory has had a corrosive effect on our politics leading to bad policy and suspicion and mistrust of the normal workings of government. But what appears to be the converse position carries the seeds of this same error too. If I argue that America is not the source of all good but somehow an unredeemable evil that I cannot be complicit in, I have shown myself to be the same kind of citizen the Christian nationalist is even though I don’t share his beliefs. Both he and I are fleeing from the law of the place where we are and the duties we have into a kind of “gospel” of the nation. As a Christian nationalist I might assert that I am a partaker in the good news of America because of some hidden divine plan encased in the founding. Everything good about my community comes from the past and if my neighbor disagrees they are somehow outside of God’s activity and my responsibility. But if, as one who detests the United States, I assert that its institutions need to be root-and-branch recreated in order for me to fully participate, I’ve said the same basic thing. Whether I relate God’s activity to some idealized past or eventually realized future I’ve in that moment offered myself a kind of absolution from the citizenship that my neighbor demands from me. Such are the sown seeds that have sprouted in so many of our partisan divides. Whenever you hear some cable news host screaming about the other side you can’t help but catch the underlying message: “Not your neighbor.”

We don’t fly patriotism on the flag. We live it on the ground. The daily work of our vocations, our sacrifices both great and small, and the freedom we have to worship God without any interference (unless we use this as a pretext to refuse to serve our neighbors) is what we value as Christians when we talk about the country we live in. And it’s an arena where there are both successes and failures. Two men on that boat ride to Newport violated the rights of many of their neighbors by claiming them as property. One of them remarked “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just.” American history can be a daunting record of legalized discrimination, state sanctioned terror, violence, racism and xenophobia. The legacies of much of this have been paved into our neighborhoods and still fester in our criminal justice system. And these things are not collateral damage on some road to a greater realization of the American ideal, or an indictment of the kinds of ideals that Washington carried. They are failures. Failures that have to be named, addressed, and corrected as much as possible. They point us to what we need to do in the present. If citizenship means a present duty we can’t shrug it off when we fail and still claim that title.

So, when the Fourth of July falls on a Sunday like it does this week don’t run from it. Don’t run to it if the text doesn’t demand it. But don’t be afraid to appeal to people’s patriotism to urge them to heed their neighbors. Where people are quaking under their vines and fig trees because of their immigration status, their sexual orientation, or because of the lack of resources in their homes and communities, call people to action. Where there are vocations and gifts that your neighbors need, claim them as God-given public goods. Where there is love for the military, point to the ethos of service and standing up for the weak that Jesus championed too. For too long squeamish preachers have worried so much about the abuses of patriotism that they fear to use the word and concepts at all. This avoidance of irresponsible use has only cleared the field for irresponsible pundits and politicians to turn patriotism into something it is not. It is enough to say that your congregation stands on free ground and baked into that freedom is the responsibility to make sure your community is free ground too because of the goodness of the God you worship. But after you’ve put all this in their hands don’t forget to put in their hearts the one who died for and claims people from every nation. Only through Him can we be “everlastingly happy,” as Washington phrased it.

_______

Endnotes:

[1] Texts of both these letters as well as the story of this exchange can be found at https://www.facinghistory.org/nobigotry/the-letters/letter-moses-seixas-george-washington

[2] “Demean” here carries the archaic meaning of “comport” or “behave,” not the modern one of “denigrate.”

[3] Paul Revere’s Ride by David Hackett Fisher presents not only a micro-history of the famous event but goes into detail about the covenantal nature of society in colonial Boston. 1775 by Kevin Phillips, while turgidly written, is well researched and details the work of civil society in the early part of the war.