Co-missioners,

Don’t think for a moment to skip today’s finale to the essay we started feeding you two weeks ago. We think you’ll wind up as refreshed as we were in the wonder of God’s will for humankind in Christ.

Our thanks again to Kurt Hendel for his permission to republish this piece. It calls for the widest possible reading, and not only by thoughtful Lutherans but by Christians of every stripe.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

On the Question of Salvation Outside the Church: Luther vs. Luther (Part 3 of 3)

By Kurt K. Hendel

How does this analysis of Luther’s notion of the hidden and revealed God address the assertion that there is no salvation outside the church and how does it shed light on the church’s calling to be Christ’s witnesses today? It is not surprising that in their own time and place Luther and most of his European contemporaries, whether they were supporters or opponents of the Reformation, agreed with the historic assertion that salvation is limited to the community of the faithful, the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church. This was neither a new nor a radical claim, and the church was convinced that it was called to witness Christ to the nations. The claim that the church is the realm of salvation had been made since the time of Cyprian,

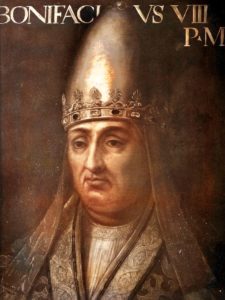

By Cristofano dell’Altissimo – Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99252525

and at the beginning of the fourteenth century Pope Boniface VIII had even asserted that all human beings must be subject to the bishop of Rome in order to be saved. [43] Many of his contemporaries rejected Boniface’s exalted vision of papal authority, but few extended salvation beyond the borders of the church. It is, of course, much more difficult to defend these traditional salvific boundaries in the contemporary, twenty-first-century context when ecumenism and interreligious dialogue are affirmed as ideals by many Christians and when absolute truth claims, a tendency toward exclusivity, or signs of religious imperialism are considered to be problematic or are rejected altogether by many within the church and surely within society in general.

Is it possible, then, to question and even reject these exclusive claims of Luther and of the broader Christian tradition without denying central affirmations of that tradition? At first glance, it surely appears that Luther’s doctrine of justification and his dialectic of the hidden and revealed God unequivocally support the assertion that there is no salvation outside the church. However, if one nuances these doctrines carefully, especially the Reformer’s notion of the Deus absconditus, and considers their varied implications, it is possible to challenge contemporary students and heirs of Luther to expand their theological and missiological perspectives.

It must be stressed, first of all, that evangelical theology clearly affirms the uniqueness of Christ as Savior and as God’s ultimate and absolutely trustworthy self-revelation. Humanity’s salvation is always impacted by and assured by Christ’s redemptive work. Hence, it is impossible to embrace a radical universalistic position on the basis of Luther’s and the Lutheran Confessions’ theological insights.

Evangelical Lutheran theology also necessitates the joyful claim that there is salvation within the church. After all, the church is the sphere of the Holy Spirit’s activity where the means of grace, the Word and the sacraments, are proclaimed and celebrated. It is precisely through those means that the Holy Spirit promises to create and nurture faith. In the church forgiveness of sin is granted to all who trust God’s promises. Although they remain sinners as well as saints, people of faith, or members of the church, are renewed and made holy through the Word and the sacraments, their very nature is transformed, and they bring forth the fruits of faith whereby they serve God and their neighbors. Their eternal destiny is assured by the gracious gifts that they receive freely for the sake of Christ. There is, therefore, salvation within the church.

Evangelical theology is, by definition, Christo-centric. In Christ God’s will for humanity is revealed with certainty and clarity, and through Christ God has accomplished God’s saving acts. The gospel is, therefore, the good news of Jesus Christ and, thus, brings life and salvation. People of faith proclaim this gospel within the church because they are nurtured by that proclamation. They are also freed, inspired, and commanded to proclaim it in the world with the conviction that God intends all to be saved, that faith is created and nurtured through the gospel, and that Christ is not only their Savior and Lord [44] but the Redeemer of all.

A Christo-centric, evangelical perspective therefore insists that the will of the Deus revelatus, the God revealed in Christ, is to save the whole creation. That will has not been abrogated or superseded. However, as Luther asserts so strikingly in the Bondage of the Will, God is not limited by God’s revelation. God is, after all, also Deus absconditus whose majestic will is hidden beyond revelation. While the Reformer could not resist the temptation to explicate God’s hidden will in his diatribe against the Diatribe of Erasmus, it is more consistent with his theology, particularly with his theology of the cross and his Christology, to leave the hidden will of God alone and to approach God as God clothed in the Word, specifically in the Word Incarnate. When one does, one sees God’s back, [45] not God’s face, and meets God as Savior. Hence, God’s hidden will remains hidden, even in Christ, although God’s will revealed in Christ is trustworthy. It is also consistent with Luther’s theology to distinguish but never to separate the Deus revelatus and the Deus absconditus. Luther is not a dualistic but a paradoxical theologian. Therefore, it is theologically defensible to assume that the hidden will of God does not contradict the revealed will. It is also necessary to leave God’s hidden will alone, with the faithful assumption that humans will not know this will until they are enlightened by God with what Luther calls the “light of glory.” [46] In the meantime, they trust that the revealed will sheds light on the hidden will.

The following consequences can be drawn when one assumes such a theological stance. First, believers, particularly evangelical theologians, will resist the temptation to describe what God’s hidden will is. Rather, they will humbly and necessarily accept the reality that God chooses not to reveal God’s face, only God’s back, and that much about God remains hidden beyond revelation. They will, therefore, let God be God, both when God is revealed and when God chooses to remain hidden. Secondly, people of faith will approach the hidden God as they do the revealed God, namely, in and through Christ and with the Christological assurance that it is God’s will to save. Thirdly, on the basis of the doctrine of justification by grace through faith as well as the dialectic of the hidden and revealed God they will confess that God alone can and does save and that God does so in and through the Christ. With such a perspective evangelical Lutheran Christians, who strive to be theologians of the cross, will proclaim Christ, even as they avoid speculating about the fate of those who have not yet come to faith and who do not confess Christ. They, therefore, need not assert the condemnation of such people. Rather, knowing that only God saves and confessing that they cannot and dare not delve into God’s hidden will, they leave the fate of those who are not members of the church in God’s hands. They do so with the assurance that in Christ God has saved all, and with the expectation that God intends to bless all with the benefits of Christ’s redemptive acts. That expectation is warranted because the hidden God is none other than the revealed God, and people of faith consider God’s hidden will in light of God’s revealed will. [47] Hence, they must be open to the possibility that the hidden God has done and will continue to do surprising things for the sake of God’s creation. There is, after all, much that God has chosen not to reveal even in the Word. [48] If part of the hidden will of God is to justify people in ways of which believers are not aware, that is God’s prerogative. As Luther argues so consistently, the person of faith is called to believe and to confess that God’s actions are just, no matter what God does, because God is just. God’s promises in Jesus the Christ, witnessed by the prophets, apostles, and believers throughout the ages, are not abrogated, even if God has another plan of salvation. God has kept those promises in the past and continues to keep them. The church is a visible manifestation of that fact. Thus, God’s revealed will is trustworthy, and God’s self-revelation in Christ is sure. God’s hidden will, no matter what it is, will not contradict God’s revealed will. Christ is the Christian’s assurance of that fact and so is the believer’s faith.

It is crucial to note, however, that people of faith who affirm the gospel and the dialectic of the Deus revelatus and the Deus absconditus cannot become universalists. They cannot claim with certainty that there is salvation outside the church, even as they need not assert that there is no salvation outside the church. To do either would make them theologians of glory rather than theologians of the cross. They are, however, called to proclaim Christ joyfully and humbly, with the assurance that it is God’s will to save and that God creates and nurtures faith through that proclamation. They are called to proclaim Christ because they are assured that He is Savior and that the Holy Spirit creates faith in and through the proclamation of Christ, through the gospel. Of this people of faith in Christ are certain. This is the gift that they have received, not to hoard, but to share, and so they witness Christ, faithfully, humbly, and with the confidence that He is God’s ultimate gift to humanity and the whole creation. The rest must be left in God’s hands because God alone saves, justifies, and converts. Humans, even believers, cannot determine their own fate or the fate of others. That is God’s prerogative. The revealed God assures believers that God is Savior. The hidden God prevents them from limiting God’s freedom or possibilities, even in matters of salvation. Their concern and their calling are to be God’s instruments of grace in the world, and they are assured that they are precisely that when they are Christ’s witnesses.

Endnotes

[43] See Boniface VIII’s bull Unam sanctam from the year 1302. [44] Luther defines “Lord” as “Redeemer” in his explanation of the second article of the Creed in the Large Catechism. See Book of Concord, The Large Catechism, The Creed, II, 434, 27. [45] See LW 31, 52, “Heidelberg Theses,” Explanation of Thesis 20. See also Exodus 33:18-23 which informs Luther’s theological insights. [46] LW 33, 292. [47] A practical manifestation of this perspective is the church’s stance regarding the fate of infants who have not received emergency baptism. [48] The authors of the “Formula of Concord” also caution evangelical Christians to leave God’s hidden will alone and to find comfort and assurance in God’s revealed will. Yet, they assume that some will be saved and some will be condemned, although they reject the doctrine of double predestination. See, for example, Book of Concord, Epitome, XI, 517,1-520,22; Formula of Concord, Solid Declaration, XI, 643,13-645,29, 649,52-651,68.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.