Painting by G. Baumann: “Brenz and Isenmann at Luther in Heidelberg, 1854”. The picture hangs in the church of St. Katharina in Schwäbisch Hall and shows the reformer Martin Luther with the reformer Johannes Brenz and pastor Johann Isenmann at the disputation Luther on April 26, 1518 in Heidelberg.

Co-missioners,

Here is the second installment of an essay by Kurt Hendel, first published by the journal Currents in Theology and Mission in 2008. If you haven’t worked through last week’s first installment, you’ll want to do that before you dig in here.

And dig you should. Carefully. Thoroughly. For one thing, you’ll be refreshed in some essential aspects of Luther’s thought that merit far more attention than they’re getting these days, even from Lutherans. Such shallow thinkers we are by contrast.

More to the point, you’ll encounter an assertion that may well startle you—and in it the key to Hendel’s argument as it will play out next week. Luther, Kurt will observe, was not a consistent theologian. In some of his most important work he violated his own bedrock principles about how theology should be done. Luther vs. Luther, in other words. Look for this as you read. Mark it. Learn it. Inwardly digest it as you prepare for next Thursday’s conclusion.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

On the Question of Salvation Outside the Church: Luther vs. Luther (Part 2 of 3)

By Kurt K. Hendel

The dilemma [of Lutheran theology that must be addressed at this point] is inherent in the Lutheran doctrine of justification, and it is related to the assumption that some are saved while others are not. The doctrine of justification asserts that God alone saves and justifies, that God has already redeemed humanity in Jesus Christ, and that the justification of all is God’s intention. Yet, the Lutheran tradition has also consistently maintained that there is no salvation outside the church and that all are, therefore, not saved or justified. The dilemma is that God, who has already redeemed all in Christ, apparently does not justify all. As has already been noted, Luther argued that since the fall all human beings who are not regenerated are enemies of God who cannot obey God’s will and fulfill the law. Therefore, only God can and does save. No one can do anything to prepare for or merit salvation. In light of their sinful nature, all human beings are the same in God’s sight and equally incapable in matters of salvation. Why, then does God overcome the enmity and rebellion of some, grant them faith, and justify them but not others?

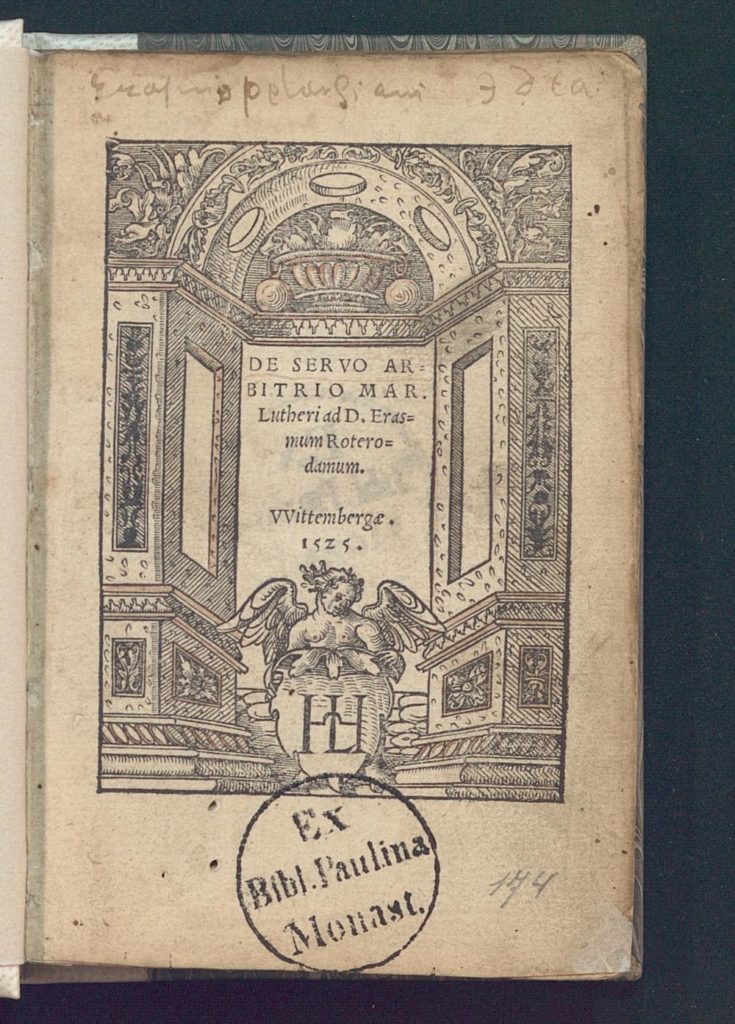

By Martin Luther – http://sammlungen.ulb.uni-muenster.de/hd/content/pageview/752726, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45704865

Seeking to avoid any hint of synergism, the Lutheran confessional writings maintain that the blame for people’s condemnation must be ascribed to the devil and the perverse human will, even as they reject that the human will somehow cooperates with God in conversion. [15] This is also Luther’s most consistent position. [16] However, this explanation is found wanting. After all, the will of every unregenerate human being is perverse and at enmity with God, and the devil always opposes God’s saving and justifying activity. There is, therefore, no essential distinction between one person and another. Furthermore, only God can and does save and justify. Human beings cannot cooperate with God in their justification. Indeed, any attempt to do so is a usurpation of God’s role and fails to let God be God. Hence, the questions persist.

Having noted the challenging dilemma raised by Luther’s assertion that we are saved by grace through faith alone, it is now necessary to explore the Reformer’s dialectic of the hidden and revealed God [17] as a theological resource that sheds important light on that dilemma and on the assertion that there is no salvation outside the church. This dialectic also has the potential of expanding the theological, ecumenical, and missiological horizons of contemporary evangelical theologians without necessitating a universalistic position. While this dialectic is apparent throughout Luther’s vast corpus of writings, he explores it quite intentionally and extensively in the “Heidelberg Theses” and in the Bondage of the Will. Hence, these two writings serve as the chief sources of the discussion which follows.

The Deus revelatus—the revealed God—is a particular focus of attention in the “Heidelberg Theses.” Romans 1:19-25, I Corinthians 1:17-31, and the theophany recorded in Exodus 33:18-23 clearly inform Luther’s striking assertions. With his penchant for paradoxical thinking, Luther proposes that God’s ultimate self-revelation is in hiding. He cautions those who wish to be theologians of the cross, that is, true theologians, not to focus on the invisible things of God revealed through God’s mighty works of creation, such invisible things as God’s “virtue, godliness, wisdom, justice, goodness, and so forth…. The recognition of all these things does not make one worthy or wise.” [18] The reason why true theologians should not seek the invisible things of God revealed through God’s mighty acts of creation is explained by St. Paul in Romans 1. It is because humans have misinterpreted these natural revelations, have not honored God, have become fools while claiming to be wise, and have “exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal men or birds or animals or reptiles.” Thus God gave them up to their sins “because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator….” [19] St. Paul notes in this passage, and Luther agrees with him, that while God is revealed in the wonders of creation, human beings have misinterpreted and misused that revelation and have become idolaters, making God into their image rather than recognizing God as God wishes to be known and confessing God to be God. For this reason, asserts Luther, God has chosen to reveal God’s essence in a radically different and surprising way, in what the Reformer calls the “back” or “visible” things, namely, in weakness, in folly, in the incarnation, and on the cross. Luther clearly reflects Paul’s insights in Romans 1 and in I Corinthians 1 as he notes,

Because men misused the knowledge of God through works, God wished again to be recognized in suffering, and to condemn wisdom concerning invisible things by means of wisdom concerning visible things, so that those who did not honor God as manifested in his works should honor him as he is hidden in his suffering. As the Apostle says in I Cor. 1[:21], “For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, it pleased God through the folly of what we preach to save those who believe.” Now it is not sufficient for anyone, and it does him no good to recognize God in his glory and majesty, unless he recognizes him in the humility and shame of the cross. [20]

It is crucial to note Luther’s emphases in this passage. God is revealed and wishes to be recognized in the suffering, humility, and shame of the cross. However, God is hidden in suffering. Hence, God is revealed by hiding, and only this revelation is sufficient and redemptive. Those who seek to know the invisible things of God, namely, God’s glory majesty, wisdom, and justice, through the wisdom of natural revelation are chastised as theologians of glory by Luther. They will never know God, at least not as Savior. On the other hand, those who focus on the incarnate Christ suffering the shame and humiliation of the cross, that is, on the visible things, are theologians of the cross and recognize the very nature and work of God in that hidden revelation.

What God is revealed by hiding on the cross as the Incarnate One? In Christ theologians of the cross see God as God wants to be seen, as a God who exercises power in weakness, whose glory is shame and humiliation, who brings life by means of death, whose suffering leads to resurrection, whose divine majesty is clothed in human flesh. It is no wonder that Luther maintains paradoxically that God is hidden in God’s ultimate self-revelation. That is why faith is absolutely necessary in order to recognize God in the crucified Christ. It is, however, only in the Christ that God chooses to be revealed. It is only through the Christ that God and God’s will are known. Luther supports this assertion by noting Philip’s request to Jesus in John 14:8: “Lord, show us the Father, and we shall be satisfied.” Jesus responds: “Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me, Philip? He who has seen me has seen the Father….” [John 14:9] Luther concludes, therefore: “For this reason true theology and recognition of God are in the crucified Christ….” [21] Thus in the Christ God is revealed by hiding, and in Christ God is revealed as the One who saves.

While Luther’s focus in the “Heidelberg Theses” is on the Deus revelatus, the Reformer presents a challenging, yet fascinating, depiction of the Deus absconditus—the hidden God—in the Bondage of the Will. This lengthy and complex work is one of Luther’s most important and profound theological treatises. It not not only illustrates the boldness and dialectical creativity of his thought, but also raises crucial questions regarding the theological consistency and validity of his biblical exegesis in this treatise. The radical nature of Luther’s understanding of the hidden God is surely evident in this work.

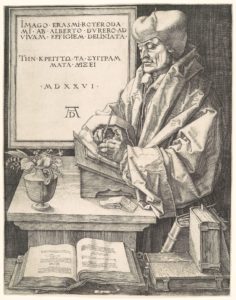

By Albrecht Dürer – https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/336231, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9642095

Luther warns that the theologian and believer must distinguish between the God preached, or revealed, and the God hidden—“that is, between the Word of God and God himself.” [22] The hidden God, or “God himself,” does many things and wills many things that are not revealed, even in Scripture. [23] Hence, God is hidden “behind and beyond Scripture.” [24] While he does not say so explicitly, the implication of Luther’s arguments is that the hidden will and the hidden deeds of God are not even apparent in and through God’s ultimate self-revelation, namely, Jesus Christ. While the Reformer also insists that human beings must leave this hidden, majestic God alone [25] and focus on the Word which witnesses to the Incarnate Word, he ignores his own advice and explicates what the Deus absconditus wills and works. In doing so, Luther becomes a theologian of glory who seeks to look into the face of God rather than a theologian of the cross who focuses on God’s back and, hence, on the visible things of God. Thus, Luther contradicts his own theological method as he explores the hidden will of God and asserts boldly that God wills to reject some even as God wills in the revealed will that all sinners are saved. Luther essentially posits a doctrine of double predestination in the Bondage of the Will and maintains that the condemned suffer their fate in accordance with God’s inscrutable will. Indeed, he affirms St. Augustine’s assertion that God works both good and evil within people, [26] although he nuances that assertion later in the treatise and explains that God uses the evil that is already within a person to work evil by means of that individual. [27] In order to support his position regarding God’s will to condemn, Luther cites scriptural evidence and points out that God hardened Pharaoh, [28] foreknew that Judas would betray Jesus, [29] and loved Jacob but hated Esau. [30] He also examines the passages from Isaiah 45 and Romans 9 regarding the potter and the clay. [31] The Reformer stresses that this majestic, hidden will has no standards but itself [32] and that God is no more unjust when God condemns the undeserving than when God graciously rewards the undeserving. [33] The impact of St. Paul’s discussion in Romans 9 is clearly evident as Luther seeks biblical warrant for the doctrine of double predestination. Luther’s chief theological mentors, Paul and Augustine, are obvious resources as he carries on his literary dialogue with his famous antagonist, Erasmus of Rotterdam.

While elucidating God’s hidden will, Luther is also careful to dictate what the human response to the will and work of the Deus absconditus must be. Although he does not follow his own advice in the Bondage of the Will, he insists that since God is God and humans are creatures, they cannot probe into the mystery of God’s hidden will, [34] nor dare they question or judge it. [35] Rather, they must “pay attention to the word and leave that inscrutable will alone….” [36] God cannot be approached in God’s majesty but only “insofar as he is clothed and set forth in his Word….” [37] The hidden will of God can only be revered, feared, and adored. [38] The ultimate human response to the hidden God as well as the revealed God is, therefore, faith. Thus, Luther maintains that it is the “highest degree of faith” to believe that God is merciful when God saves so few and damns so many. [39]

As one considers the challenging nature and content of Luther’s notion of the Deus absconditus, the question arises why the Reformer found it necessary to articulate these ideas. A careful reading of the Bondage of the Will suggests the following answer. Methodologically, Luther obviously viewed the content of his argument as an effective and convincing response to the anthropological assertions of Erasmus. However, he also had important theological reasons for stressing the majestic and hidden God and the related doctrine of double predestination. For Luther, the doctrine of justification and, hence, the gospel were at stake in his debate with Erasmus. Therefore, he sought to reject the freedom of the will [40] and to stress that humans are totally dependent on God for their spiritual destiny. [41] He also wanted to emphasize the necessity of faith in matters of salvation and justification. [42] Perhaps most importantly, he eagerly defended the absolute freedom and non-contingency of God so that God is not only able to make promises but to keep them as well. After all, the eternal destiny of humanity depends on God’s freedom and power to save.

—to be continued

Endnotes

[15] Book of Concord, Apology of the Augsburg Confession, XIX, 235; Formula of Concord, Epitome, XI,518,13-519,15; Formula of Concord, Solid Declaration, II, 547,17-549,24, 552,44-45; Formula of Concord, Solid Declaration, XI, 653,78-82. [16] LW 31, 58-60; LW 32, 226; LW 33, 65; Book of Concord, The Smalcald Articles, III,1, 310,1-311,11. [17] See Isaiah 45:15. [18] LW 31, 52; Explanation of Thesis 19. [19] Romans 1:23; 25. [20] LW 31, 52-53, Explanation of Thesis 20. [21] LW 31, 53, Explanation of Thesis 20. [22] LW 33, 140. [23] LW 33, 140. [24] Paul Althaus, The Theology of Martin Luther, tr. by Robert C. Schultz (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966), p. 277. [25] LW 33, 139: “God must therefore be left to himself in his own majesty, for in this regard we have nothing to do with him, nor has he willed that we should have anything to do with him. But we have something to do with him insofar as he is clothed and set forth in his Word, through which he offers himself to us and which is the beauty and glory with which the psalmist celebrates him as being clothed.” See also LW 33, 140. [26] LW 33, 58. [27] LW 33, 178. [28] LW 33, 179. [29] LW 33, 194-195. [30] LW 33, 195-202. [31] LW 33, 203-206. [32] LW 33, 181: “He is God, and for his will there is no cause or reason that can be laid down as a rule or measure for it, since there is nothing equal or superior to it, but it is itself the rule of all things. For if there were any rule or standard for it, either as a cause or reason, it could no longer be the will of God.” [33] LW 33, 207. [34] LW 33, 188. [35] LW 33, 61, 139, 290. [36] LW 33, 140. [37] LW 33, 139. [38] LW 33, 139, 140, 188. [39] LW 33, 62, 174. [40] LW 33, 64 and numerous other citations throughout the Bondage of the Will. [41] LW 33, 191. [42] LW 33, 62.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.