Luther’s Infamous “On the Jews.” An Assessment (Part 1)

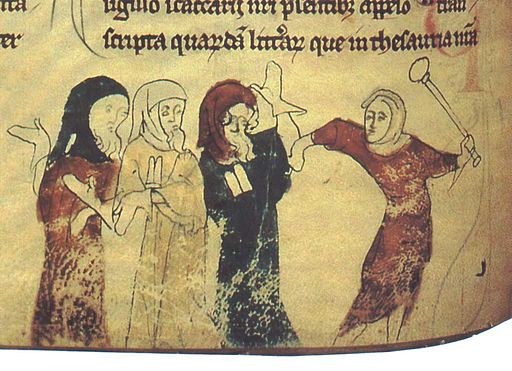

Miniature showing the expulsion of Jews following the Edict of Expulsion by Edward I of England (18 July 1290) from Wikipedia

Co-missioners,

An eruption of racist slaughter left ten people dead in Buffalo last week. On Sunday another was killed and more were injured at a church in Laguna Woods, California, for the sin of being Taiwanese. Anyone inclined to think in Martin Luther’s categories will refer to this as the raging of the devil.

Comes a dreadful irony. The devil raged through Martin Luther too from time to time, and at no point more horribly than in his tract of 1543 entitled “On the Jews and their Lies.” One plausibly draws a line from that to the slaughter of racist slaughters that we know today as the Holocaust.

What shall those of us predisposed to thanking God for Luther make of this terrible tract, the worst of all his works? Kurt Hendel wrestles with this in a hitherto unpublished essay that he shared with us a few months ago. Its length is such that we pass it on to you in two parts. Today’s piece will set the stage for Kurt’s reflection on the tract itself. Look for that next week.

Kurt—Dr. Hendel, as a few of us knew him in student days—taught church history at Seminex and later at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, where his current official title is “The Bernard, Fischer, Westberg Distinguished Ministry Professor Emeritus of Reformation History.” His two-volume translation of selected writings by Johannes Bugenhagen was issued by Fortress Press in 2015. Our thanks indeed for his contribution to Thursday Theology! (And if you like this contribution, we’d love to see you at this month’s Table Talk where Kurt will be the discussion leader!)

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

Luther and the Jews

by Kurt K. Hendel

Martin Luther’s attitudes toward and advice regarding the Jewish community are an extremely complex and difficult topic because of the long history of Christian antisemitism; because of the tragedy of the holocaust or Shoah; because of the continuing manifestations of racism around the world, including the United States; because religious convictions, specifically Christian ideals, are so often cited as justification for racist attitudes and actions; because Martin Luther inspired the hope of fostering different, more positive attitudes toward Jews but later advocated persecution of Jews; and because the Reformer ultimately contradicted the gospel as well as his own admirable methodological principle regarding matters of faith and conscience. At the same time, it is a topic that should not and cannot be ignored because of its diverse implications and because it may inspire God’s people to evaluate their particular theological and cultural heritages; repent for the sins of the past and the present; and strive for justice, respect, and love for the neighbor in their dealings with people of other cultures, ethnic groups, and religions. It is also important that we examine Luther’s attitudes, motivations, and actions with care in order to evaluate him properly and fairly. Let me say at the very start, however, that we can only seek explanations, insights, and historical clarity. For clear theological and ethical reasons, people of faith should not seek to make excuses for Luther, defend him, or justify his proposals regarding the Jewish people during the last years of his life.

My intention in this presentation is to summarize Luther’s attitude toward and comments about the Jews, analyze the potential reasons why he wrote what he did, and offer necessary critiques. It is my hope that my words will foster careful evaluation of Luther’s perspectives, intentions, actions, and theological insights and invite careful and faithful consideration of the implications of the gospel as contemporary Christian believers evaluate their own attitudes toward and dealings with people of diverse ethnic heritages and religious beliefs.

The negative relationship between Christians and Jews and the persistent antisemitism that has characterized Western Christian societies throughout the last two millennia is particularly ironic because, as Luther points out in the title of his first major work that deals with the Jews, Jesus, the son of Mary whom Christians confess to be the Son of God and the Savior of the world, was a Jew. The earliest followers of Jesus were Jews as well. Thus, our closest spiritual relatives are the Jews. Indeed, the Christian tradition is, in fact, the Judeo-Christian tradition since Christianity has affirmed so much of the Jewish heritage, and Christians have always seen themselves as the heirs of the promises that God made to God’s people in ancient times. All Christians are fully aware of these realities and celebrate and affirm their Jewish scriptural heritage. Yet, the relationship between these two communities of spiritual and religious siblings has been strained from the very beginning.

The New Testament writings, particularly the Book of Acts, attest to this reality. Initially, the Jewish religious leaders and their supporters opposed and even persecuted the followers of Jesus because of the claims that the Christians made about Jesus and because the Jewish leaders insisted that Jewish Christians were usurping or rejecting their sacred Jewish traditions. However, the earliest Christians, particularly those centered in Jerusalem, viewed themselves to be pious and faithful Jews. They continued to keep the Jewish laws and to worship in the temple, but they also confessed Jesus as the promised Messiah, as the Anointed One, as the Christ.

Because the majority of the Jewish people rejected Jesus and His message, because that message was addressed to the Gentiles as well as the Jews, and because of the missionary and theological activity of the early church, particularly of St. Paul, the early Christian community quickly became largely Gentile. Its center of activity shifted from Jerusalem and Palestine to such areas as Asia Minor, North Africa, and eventually the Greek peninsula, Italy, and the rest of the western Mediterranean world. While the Romans initially viewed Christianity as a Jewish sect, by the second century Christians and Jews had become two distinct communities. Both Christians and Jews now claimed to be the people of God and the heirs of God’s promises, although Christians maintained that Jesus was the fulfillment of those promises. That claim and confession was obviously the major cause of division between Christians and Jews.

During the fourth century, Christianity became a tolerated and, ultimately, the official religion of the Roman Empire. While this official, imperial recognition and patronage caused many problems for the church, some of which are apparent in the churches of Europe and even North America to this day, Christianity also greatly benefited from this new reality, especially institutionally. The church surely experienced tremendous growth. It also survived the demise of the Roman Empire, and during the Middle Ages, the church became the dominant institution, socially, politically, culturally, economically, and spiritually in the European context.

Because of their own economic activity and the loss of their land, Jews also moved into the Western Mediterranean and ultimately the European worlds. During the Middle Ages various attempts to convert Jews were pursued by the church, especially the friars. None of these efforts were successful from a Christian perspective, even when force and persecution were used periodically. Both the faithfulness of the Jews and the ineffectiveness of Christian proselytization, especially in light of the discrimination, ghettoizing, and expulsions of the Jews from parts of Europe, help to explain the minimal number of conversions. Some Jews did convert, but not always because of religious convictions. Economic concerns, the fear of persecution, the quest for social status, and the desire to remain in their homes compelled or inclined some Jewish families to convert. Unfortunately, when they did convert, they often came to the attention and fell under the authority of the suspicious and watchful eye of the Inquisition. Christian Jews were often suspected of crypto-Judaism and were persecuted as a result. They were also periodically and regionally protected by the papacy and by political rulers, largely because of their economic influence.

During the course of the Middle Ages, Jews were either expelled from European territories, or they were forced to live in ghettos. They were not free to participate in professions of their choice but were compelled to be bankers and money lenders and were then resented for fulfilling those callings. All kinds of superstitions and rumors also developed about the Jews, probably to justify the attitudes, biases, and actions of Christians. Jews also often became scapegoats and were blamed for various problems and disasters faced by European Christendom.

By Luther’s time, Jews had been expelled from most of the German territories, including Electoral Saxony, although they were often allowed to travel in these regions in order to pursue commercial activity. Anti-Jewish polemics persisted throughout the sixteenth century and spanned the new religious landscape. For example, John Eck, arguably the leading Roman theologian in the German territories; Martin Bucer, the irenic leader of the Reformation in Strasbourg; and Martin Luther all wrote highly polemical treatises against the Jews.

After this brief contextual sketch, let me focus on Luther.

1. 1523—That Jesus Christ was born a Jew (Luther’s Works 47:57-98)

Early in his career Luther expressed what could be called an enlightened and tolerant attitude toward the Jews. His stance was quite atypical and could have inspired opposition. Such opposition apparently did not occur, perhaps because his opponents had so many other reasons for criticizing and condemning Luther. Obviously, his position regarding theological and ecclesiastical matters concerned his opponents much more.

Statue of Martin Luther. Image made with Canva

In his 1523 treatise, which was written not so much to make a statement about the Jews but to defend himself against the charge that he rejected the virgin birth, Luther criticized the church and Christian society in general for their unfortunate treatment of the Jews and for spreading and believing a variety of rumors and superstitions about the Jews. The Reformer concluded that it is no wonder that the Jews have rejected the gospel since those who proclaimed Christ treated them so brutally and clearly disrespected them. It was also not surprising that the Jews rejected the gospel since it had been corrupted, obscured, and compromised by the pope and his followers.

Luther’s proposal, in response to these realities, was that Jews should be treated humanely and that the gospel should be preached faithfully and purely. Specifically, he emphasized that Christians should deal gently with Jews and first help them recognize that Jesus is the Messiah on the basis of their own Scriptures. Then they might be able to convince them that Jesus is the Son of God. Force should be avoided, and biblical and theological instruction should be the proselytization method that is employed by the church. Luther also rejected various anti-Jewish popular beliefs and insisted that Jews should not be banished but should be allowed to live among Christians. Love and the faithful witness of Christ and the gospel should characterize the relationship between Christians and Jews.

It is crucial to note that the goal of this gentle strategy was the conversion of the Jews. Luther was not suggesting that the Jewish faith should be accepted and tolerated. He was obviously convinced that the Jews had rejected God’s promises by rejecting Christ. He did hope, however, that a radical change of attitude toward and treatment of the Jews, as well as the faithful proclamation of the radical good news that is the gospel, would result in Jewish conversions and their confession of Christ. Luther defended the Christian claim that Jesus is the Messiah by means of a Christological interpretation of the Old Testament messianic prophecies. By doing so, he hoped that the Jews would be convinced on the basis of their own Scriptures. It is crucial to note, therefore, that in 1523 Luther urged Christians to preach the gospel to the Jews because of his conviction that it is God’s message of life and salvation for all people. The Reformer thus sought to be faithful to the gospel, and he hoped that the Jews would be saved and justified by means of this gospel proclamation. He did not discriminate against the Jews or consider them to be less worthy than his fellow Germans or other Europeans. He also did not call for their persecution or their expulsion. Indeed, he wanted them to be welcomed in Christian territories so that the gospel could, in fact, be preached to them. Faithful proclamation of the gospel and humane treatment were Luther’s proposals as he envisioned Christian-Jewish relationships early in the Reformation period.

—to be continued

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community