Co-missioners,

We celebrated Easter four days ago. For the next several weeks our thoughts in church will be focused squarely on the new age God launched through our Lord’s resurrection. Meanwhile we continue with the rest of the world to stumble through the old age of sin and death. Comes the question: what is God’s role, if any, in shaping that old age? Or more broadly put, what “meaning” might we extract from its unfolding history?

Matt Metevelis takes up this question today in a review of a book published last June about the collapse of the Roman empire in the west. His conclusions will unsettle many Christians, we think, though not the ones who grasp the distinction between Law and Gospel.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

How the Old Age Works (A Book Review)

by Matthew Metevelis

The Fall from Below

A review of Douglas Boin’s Alaric the Goth: An Outsider’s History of the Fall of Rome

(New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton, 2020)

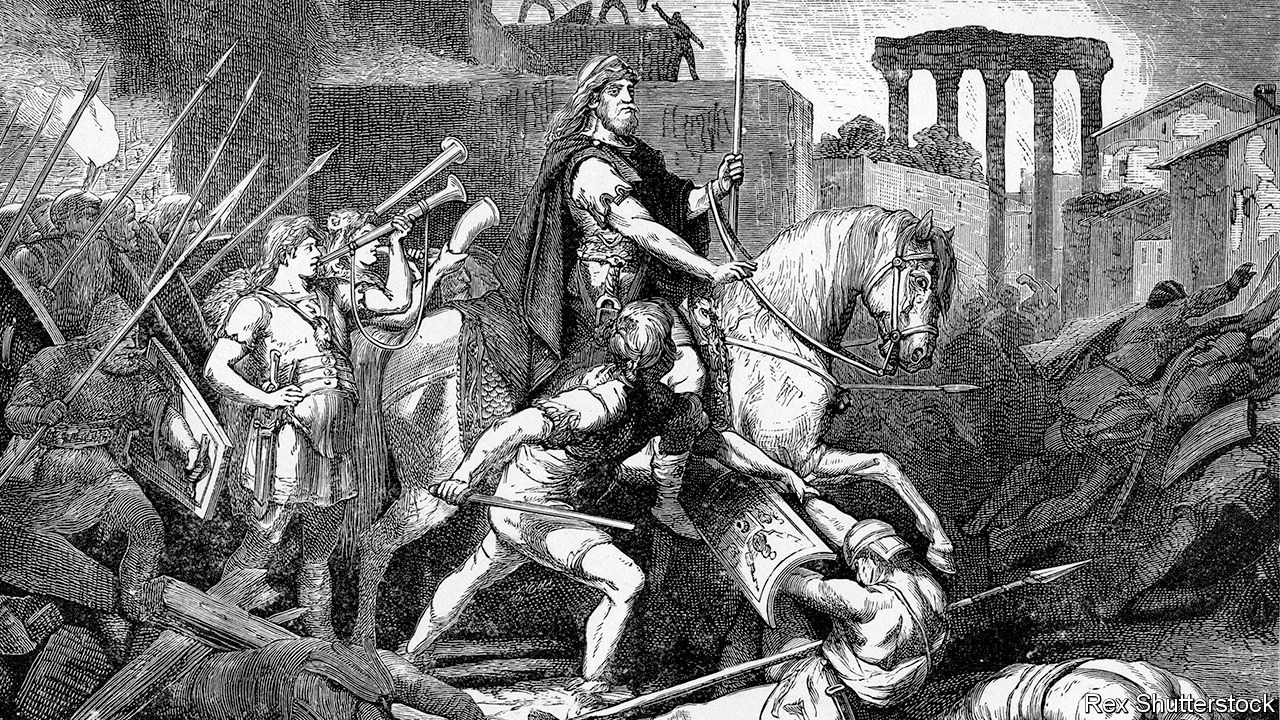

We don’t know about the fall of Rome as much as we imagine it. Barbarian hordes breaking down gates and torching temples fill the scenes that play out in our minds. Rome’s demise has become a tale told in dusty volumes about the tragic limits of human aspirations and institutions. Everything falls one day. Sometimes pundits and essayists invoke it to give warnings about overstretched empires or a decadent culture. While these retellings contain truth, they stretch the events from fact to fable and from history to myth.

Douglas Boin, a historian at St. Louis University, reclaims the last decades of the western empire for history. The life of Alaric, a Gothic “outsider” responsible for the infamous sack of Rome in 410 CE, provides a narrative device both intimate and unique. Alaric was born a Goth on the banks of the Danube and was subjected to the rustic and dangerous childhood of those who lived at the periphery of the Roman empire. Kidnapping and slavery by ambitious Romans was common. The Romans valued the fierce and hardy Goth as soldiers. Alaric fought in campaigns across the empire against the enemies of the emperor Theodosius. When Theodosius died and order in the empire broke down Alaric rose through the ranks among his Gothic peers but was denied promotions by the imperial administration and had difficulty garrisoning and feeding his troops. After constant failures in agreements and truces Alaric attacked and pillaged Rome in 410.

Douglas does a masterful job relating all this history in writing that rivals some of the best historical novels. But what I find to be most rewarding is his extensive scholarship as a social and cultural historian. This makes him able not only to let the reader know when gaps appear in the record but also to pull in details both literary and archeological to propose how better to understand and speculate about those gaps. Most of the “primary” sources for the period (Zosimus, Jar) wrote much later and Boin gives ample explication of their perspectives while providing a sober assessment of their limitations. The story of Alaric is a puzzle without all the pieces, but Boin is able to make these shortcomings in the record more illuminating than frustrating.

Douglas does a masterful job relating all this history in writing that rivals some of the best historical novels. But what I find to be most rewarding is his extensive scholarship as a social and cultural historian. This makes him able not only to let the reader know when gaps appear in the record but also to pull in details both literary and archeological to propose how better to understand and speculate about those gaps. Most of the “primary” sources for the period (Zosimus, Jar) wrote much later and Boin gives ample explication of their perspectives while providing a sober assessment of their limitations. The story of Alaric is a puzzle without all the pieces, but Boin is able to make these shortcomings in the record more illuminating than frustrating.

Historical reconstruction should be very welcome with these events. When we think of them we are at the mercy of other “outsiders.” Augustine and Jerome heard about the pillaging of Rome from hundreds of miles away. They both framed the horrific events into a larger narrative about the fall of the kingdom of man and the rise of the kingdom of God. For them these apocalyptic events heralded the dawn of a new age in which the triumphant kingdom of Christ would emerge triumphant. Never mind that the empire continued in the east for another thousand years, or that Latin would remain a dominant language in thought and administration for just as long, or that for most people living in the Western empire life did not change very significantly when ruled by Gothic kings instead of Western emperors. The narrative of a “fallen” Rome would remain. The young Edward Gibbon, an aspiring politician and writer, was inspired to compose a history of Rome while strolling through the ruins of the Forum on a sleepless night in 1758. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire became the magisterial fruit of that ambition. The fall of Rome had been a watershed, Gibbon argued, but instead of launching the glorious age of Christ it had left the world tottering in superstition and decay for centuries. Whether pleased or appalled by its outcome, Augustine and Gibbon agree on this apocalyptic understanding of Rome’s fall.

Boin’s book left me with a different impression of those events. Instead of bemoaning the inevitable decay of an over-stretched empire, Boin shows how the empire emerged in Alaric’s time as the fundamentally strong but tortured domain of petty despots and narrow-minded politicians. Instead of the orgiastic bacchanals that inflame the popular conceptions of this period, Boin’s social history expertise reveals a public obsessed to violence and distraction with chariot races. They pursued status and wealth even to the point where wealthy women would pay crowds to fawn over them and create an aura of celebrity. At lavish parties hosts would rant endlessly about the expense of the ingredients in their food (long before Instagram made food bragging a thing). Instead of a clash of civilizations between Rome and “barbarian” tribes, Boin presents a world where Roman, Goth, and so many other peoples and cultures had become tied together by economic, social, and military bonds. But these bonds were strained to the point of breaking by exploitation and cultural chauvinism. And instead of faithful Christians enduring persecution and waiting to take over and build a better world, Boin points to a community that was very much a part of the problem. In other words, I found a world much closer to home.

Boin persuasively argues that as contacts and ties of interdependence between Romans and other peoples increased so did notions of Roman “exceptionalism” which expressed itself in cultural terms as the distance between Roman and “barbarian.” Roman senators became obsessed with this kind of language even as Rome came to depend upon Goths for military and economic needs. And the Christians of the time, rather than urging compassion and hospitality, defiantly clung to their new prerogatives and shifted quickly and comfortably from the persecuted to the persecutors. Boin describes these issues on pages 126-127:

“A Goth in Alaric’s post would not have gone unnoticed. During his Illyricum years, Bishop Synesius, motivated by an increasing number of Gothic promotions, published an allegory calling for the defense of Roman culture against foreigners. Set in ancient Egypt, Synesius’s story, called ‘An Egyptian Fable’ involved two brothers who were fighting for control of government. The good brother wanted to protect Egypt from the influence of the malevolent ‘Scythians.’ [In Roman literature, Scythians were regularly used as a cipher for Goths because they shared a northern origin.] ‘An Egyptian Fable’ found an audience among Romans who already held immigrants in contempt.

“Other Romans twisted chapter and verse of the well-nigh sacred text of Homer to fit their bigotry. In order for the Roman Empire to recover its military might, the government should prohibit foreigners from advancement, they said, and the emperors should act aggressively to “drive out these ill-omened dogs.” In Homer’s Iliad the off-color phrase is attributed to the Trojan prince Hector.… But recalcitrant Romans in Alaric’s day didn’t care whether they accurately understood Homer’s scene. Any quotation, from any historic author, that could support their anti-immigrant view was a legitimate weapon in those debates except, oddly, Jesus’s words. ‘I was a stranger and you welcomed me.’ But Roman Christians conspicuously never mentioned that line during the intense immigration debates of the early fifth century.”

Boin highly suggests that this history might have turned out differently had the Roman hierarchy understood the strength that it drew from its Gothic neighbors. Alaric may not have been driven to sack Rome had he been given a place equal to his valor and his esteem among the Gothic troops. And while Boin is too good a historian to engage in contra-factual speculations, the central lesson of his book is clear. Rome fell because of human failures and not historical inevitabilities.

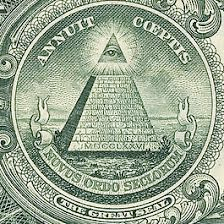

The lessons for our own age are equally clear. Following Augustine, we Americans are always looking for some providential hand in history. The Puritans brought it over on the boat and tried to build a city on a hill. “He favors our undertakings” is etched in Latin (annuit coeptis) on the Great Seal of the United States. Political arguments are rife with claims to be “on the right side of history.” And every election is now the “most important of our lifetime” presaging peace and light or a thousand years of darkness depending what cable news team you root for. We expect that history will deliver some sort of gospel somehow outside of us.

The lessons for our own age are equally clear. Following Augustine, we Americans are always looking for some providential hand in history. The Puritans brought it over on the boat and tried to build a city on a hill. “He favors our undertakings” is etched in Latin (annuit coeptis) on the Great Seal of the United States. Political arguments are rife with claims to be “on the right side of history.” And every election is now the “most important of our lifetime” presaging peace and light or a thousand years of darkness depending what cable news team you root for. We expect that history will deliver some sort of gospel somehow outside of us.

Good historians snap their fingers and take us out of that blinkered dreaming. They teach us history by paying attention. While they are aware that great impersonal forces like weather and technology can drive history the good ones like Boin can drive it down to its smallest level. History is made up of an infinite number of decisions. Will people live together as neighbors? Will leaders seek to do the right thing? Will people in thousands of vocations do their duties? Will people stand by the wisdom of turning the other cheek, welcoming the stranger, forgiving amply for the sake of enduring bonds or strong social ties, and live and die for the good of their communities? Or will they do the opposite? Will they live in fear? Will they believe false narratives and ideologies about cultural superiority or national destiny? Will they respect the dignity of their neighbor or exploit her? Will peoples around the world live and work together in peace?

These choices people make about living together determine what future generations will know about us. History lives on the ground. And on that ground these decisions are governed by the law, not a pseudo-gospel of living in the right nation or belonging to the right kind of people. History will carry on giving us nothing but the fruit of our decisions. The future for our empire is in our hands. It’s our work. Only crucified hands can give us that eternal empire of reconciliation and forgiveness for all the glut of sin and carnage we make of history. God may or may not write history, but the good news is that Christ redeems it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.