Loops and Swift Horses are Surer than Lead, 1916 by Charles M Russell. Wikipedia

Co-missioners,

This week the clear prose and sharp insights of Lori Cornell once again give Thursday Theology readers much to ponder. In this instance Lori reviews an important book that recently became available in paperback: Jesus and John Wayne, by Calvin University scholar Kristin Kobes Du Mez. Lori’s astute review prods us to move beyond shaking our finger at the toxic mix of bad theology and patriarchy, racism, and sexism that Du Mez exposes. She urges us to be theologians of the cross, trusting in Christ’s full benefits for us.

The Rev. Lori Cornell is the lead pastor of St. Mark’s Lutheran Church, Spokane, Washington. She is the long-time editor of the weekly Crossings text studies and serves on the Crossings Board of Directors.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossings Community

__________________________________________________________________

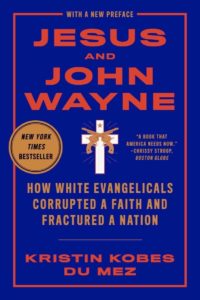

A Review: Kristin Kobes Du Mez’s Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation

by Lori Cornell

In a recent post, Diana Butler Bass resurrected a question posed by Harry Emerson Fosdick in 1922: Shall the fundamentalists win? Her conclusion: They already have.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez reaches the same conclusion with provocative, cringeworthy detail in her book Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. Du Mez’s book (issued in paperback in 2021 by Liveright Publishing) is a history of the white Evangelical church since World War II. It is rife with the makings of our current social-religious-political climate.

Du Mez’s analysis is a potent recipe that combines ingredients of American hypermasculinity, militarism, white supremacy, conditional moralism, and patriarchal religion. Her research began while she was lecturing at her conservative Christian university about Teddy Roosevelt’s rugged cowboy masculinity, American power, and how attractive both are to white Evangelicals. After the lecture two students commented how her analysis aligned with their reading of John Eldredge’s best-selling Wild at Heart, which she described as bearing “a striking resemblance to Roosevelt’s muscular, and even militaristic, ideal.” Roosevelt is not the only cowboy mentioned in the book—as the title implies.

The work traces the heavy imprint of such celebrity preachers as Billy Graham, Eldredge, and Mark Driscoll. It also takes a deep dive into the influence of James Dobson, whose cross-denominational influence on Christian parents made it possible for Dobson to cultivate a powerful political base that continues to shape the campaign messaging of many politicians to this day.

Du Mez chronicles the emergence of homeschooling crusades by the Christian right (under leaders like Gothard and Rushdoony). Her account leaves the reader contemplating whether the intent of the movement is the preservation of fundamental Christian values or the brainwashing of generations of young people—the likes of which we can only find in fundamentalist Islamic madrasas.

You may have noticed no mention of female influencers in this sharp shift in fundamentalist Evangelical culture. Du Mez does give somewhat amused focus to the impact of Marabel Morgan (The Total Woman) and Beverly LaHaye’s push to restore virility to the patriarchy and make satisfying your man fun. The author is less amused but more impressed by the monumental influence afforded Phyllis Schlafly by the Evangelical right. A conservative Catholic lawyer and activist, Schlafly nearly singlehandedly persuaded state legislatures to vote down the Equal Rights Amendment. (Here Du Mez appropriately exposes the flawed single-mindedness of feminist activists who alienated women who chose full-time childrearing, homemaking, and traditional male-female dynamics over career and “liberation.”)

One undercurrent that ripples through Jesus and John Wayne is how leaders on the religious right built a wall of silence around the sexual indiscretions and outright criminal behavior of their own. These breaches weakened the bulwark these militant, supremacist, and moralistic ideals attempted to fortify.

Worth mentioning is the author’s attention to the rise of Evangelical bookstores, publishing houses, and record labels —all of which contribute to the proliferation of conservative Christian values. These media perpetuate a narrative that likely would not withstand the scrutiny of secular publishers. Their products—under the guise of being audience-friendly for Christians—open the way not only for reinforcing law-based theology, but also for indoctrinating generations of unwitting mainline Christians with a moral framework formerly only available in fundamentalist pews.

A Cold Morning on the Range, c. 1904, Oil on canvas, by Frederic Remington. Wikipedia

Du Mez’s ability to weave together the strong warp of Evangelical fundamentalism with the prickly weft of white nationalism, tribalism, militarism, and curb appeal, make the work stand out.

All these features in Jesus and John Wayne make the book well worth reading (or downloading and listening to while walking—if it doesn’t cause your blood to boil). But for our Crossings consideration, I lift up one major theological concern that the book prompts but doesn’t answer: What lesson might we theologians of the cross take away from the development of this movement that has become the Christian right?

A wrong lesson would be to succumb to an empire-building theology of glory that is an amalgam of politics, racism, patriarchalism, and popular culture. Such temptations have already crept into mainline churches as stealthily as the serpent slithered into the Garden. Interest is such endeavors has little to do with Christ and his cross.

Preaching a “gospel” of justice and liberal activism would be no better. Du Mez has no love for the right’s characterization of Jesus as a muscular, sharp-jawed savior who comes into the world “not to bring peace but a sword”; to offer a Jesus who is only a “justice warrior” is no better. Worse, to depict Jesus as a messiah who has no sin for which to die is a gross infidelity and ripe for judgment.

Instead, I propose that we do the hard work of preaching and teaching a more robust theology—a true theology of the cross—that trusts, as Luther once said, that if Christ died for sinners, we must be sinners in need of God’s salvation.

Absent from the brand of theology described in Jesus and John Wayne is the role of repentance in the life of the church. Seldom are improprieties among leaders admitted publicly or privately. Rarely do lies have consequences. Instead, for instance, the Christian right has avoided the challenges of desegregation since the 1950s by building parochial schools that serve white student bodies, and then lobbying for school vouchers supported by federal funds. Who needs to confess or apologize when you can change your political strategy? Such politics may be shrewd but are not admirable to a theologian of the cross.

Such cunning behavior may also leave more honest Christians wondering whether it is smart to confess our corporate sins. The definitive answer is that we must. For to call evil good is to defy our witness to the power of Christ to forgive. So we speak the truth and trust in Christ even more boldly. We bring the pain that we have inflicted on our neighbor to the font and trust the one with whom we are crucified and raised. Only then can we approach our wounded neighbors with confession and a desire to make things right. Nor does such confession need to be paraded before the media, signaling some newfound virtue. Instead, as Jesus reminds us, our Father who sees us in secret will reward us.

Most poignantly, we theologians of the cross would do well to avoid the language Butler Bass exhumes from Fosdick’s 1922 speech. Let us abandon speaking in terms of winning or losing a race with fundamentalists. For to be in Christ is to win, and to die to our old selves is the world’s gain.

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.