Participation in and Transformation by the Promise

William R. Burrows

William R. Burrows, Research Professor of Missiology at New York Theological Seminary, holds a licentiate in theology from the Gregorian University and a PhD in theology from the University of Chicago Divinity School. He has worked in Papua New Guinea, in inner city ministry in the United States, and was managing editor of Orbis Books for twenty years. He is married to Linda, a school psychologist, and lives in Cortlandt Manor, New York, in the Hudson Valley, with Linda, Tabbie the cat, and Cody the dog in a post and beam house built with posts from their own red oak trees.

Orientation:

What we are about in this paper can be best understood as a gloss on Philippians 1: 4-6, and 8- 11:

In all my prayers for all of you, I always pray with joy because of your partnership in the gospel from the first day until now, being confident of this, that he who began a good work in you will carry it on to completion until the day of Christ Jesus . . . And this is my prayer: that your love may abound more and more in knowledge and depth of insight, so that you may be able to discern what is best and may be pure and blameless until the day of Christ, filled with the fruit of righteousness that comes through Jesus Christ—to the glory and praise of God.

In the office of readings for the first weeks of “ordinary time,” in the Roman Catholic church’s Liturgy of the Hours we are reading the book of Deuteronomy a chapter or so per day, followed by a text written by a father of the early church. I have been reminded forcefully in these readings that the “Law” is a great gift of God to his people. But taught by Paul the Apostle and one of his most significant modern interpreters, Martin Luther, I am also fully aware that the Gospel is not a new law, not even a new law of love, nor is it a social program. The Gospel of the New Covenant is, rather, an intensification and realization of the dominant theme of the Gospel of both Testaments — God is a God of promises. Concretely, God promises to save his people, and in Jesus we Christians believe we have the clearest revelation, indeed, the accomplishment of that promise, in the paschal mystery of Jesus of Nazareth — his transitus or passage from life through death to new life as he becomes the sender of the Holy Spirit, who is the inner witness to us that our sins indeed are forgiven and the first fruits of the realization that God’s promises to us will be fulfilled. Yet that message appears to be too good, too simple, and not concrete enough for many.

In what follows, I seek to reflect on being transformed by God’s promise, especially by celebrating the paschal mystery as the liturgical practice of remembering the promise and gathering around the table of the Lord that is the center of an authentic missional church. Why speak of being “transformed by the promise?” Because I am convinced that the reason people are so apt to reach out for now this and now that vogue cause and call it an integral aspect of putting the gospel into practice is that there is too little proof that ordinary Christians have, in fact, been transformed by participating in the paschal mystery — a mystery that includes the experience of rebirth in the Spirit.

To get at what I mean, I refer to a short section from a treatise entitled “On Spiritual Perfection” by Bishop Diadochus of Photice, which is used in the office of readings for Friday in the second week in ordinary time that I mentioned above.

He is talking about the process whereby the human self diminishes and the new self is born, a self that truly loves God above all:

Anyone who loves God in the depths of his heart has already been loved by God. In fact the measure of a person’s love for God depends upon how deeply aware that person is of God’s love for him or her. When this awareness is keen, it makes whoever possesses it long to be enlightened by the divine light, and this longing is so intense that it seems to penetrate his very bones” (Patrologia Graeca 65, cols. 1171-72).

One of the key words above is “awareness,” and the key idea is that our love for God is going to exist in proportion to our awareness of God’s love for us. In the life stories of many of the great cloud of witnesses who are our forebears in faith, one of the key things we learn is that their knowledge of God stems from an awareness of God’s grant of forgiveness for sin. It is certainly the case with Luther, for whom faith is the act of trusting the experience of forgiveness. Our problem in the church in the West today, I sometimes think, is that we have fallen into the hands of two professions: that of professional “theologians” and professional “pastors.” Now many of my best friends are theologians and pastors. Indeed, some of the most exemplary Christians I know are theologians and pastors. And I am much in favor of the church having good theologians and well-prepared pastors. Nevertheless, to be a pastor, bishop, or theologian, it is not required (a) that one “know” God in the way Diadochus speaks of, nor (b) that one be skilled in leading others to that form of participative knowledge in love of God. I am talking, though, about these people as part of professions where the price of admission is academic excellence and administrative talents. The principle requirement is not that of being skilled as mediators of wisdom and guides who can lead others into the path of being transformed by the Spirit whom Jesus promises in John 14: 16-22 when he says:

I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Counselor to be with you forever— the Spirit of truth. The world cannot accept him, because it neither sees him nor knows him. But you know him, for he lives with you and will be in you. I will not leave you as orphans; I will come to you. Before long, the world will not see me anymore, but you will see me. Because I live, you also will live. On that day you will realize that I am in my Father, and you are in me, and I am in you. Whoever has my commands and obeys them, he is the one who loves me. He who loves me will be loved by my Father, and I too will love him and show myself to him.

It is this sort of knowing Jesus and the Father as the God who first loves us, not knowing ideas about them, that Diadochus speaks of. And it is this sort of knowing that leads to transformation of one’s inner being. It is the sort of love of God that we read of in Luke’s gospel in Zechariah’s song (Luke 1:76-79):

And you, my child, will be called a prophet of the Most High; for you will go on before the Lord to prepare the way for him, to give his people the knowledge of salvation through the forgiveness of their sins, because of the tender mercy of our God, by which the rising sun will come to us from heaven to shine on those living in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the path of peace [my Italics].

There is a knowledge of God that comes from experiencing the forgiveness of our sins. If you read the gospels straight through with an ear to how often Jesus speaks of forgiving sins, it is an amazing experience. It is not the sort of feeling one gets if a judge forgives a traffic violation. In fact, the word “forgiveness” itself may mislead us in our age. Something far deeper is at stake here, and it is not too much to say that Jesus’s miracles are worked to show that the one who has the power to heal and read people’s minds, also has the power to forgive sins and grant peace of heart and mind.

In the high priestly prayer, Jesus says:

Unless I go away, the Counselor will not come to you; but if I go, I will send him to you. When he comes, he will convict the world of guilt in regard to sin and righteousness and judgment: in regard to sin, because men do not believe in me; in regard to righteousness, because I am going to the Father, where you can see me no longer; and in regard to judgment, because the prince of this world now stands condemned. I have much more to say to you, more than you can now bear. But when he, the Spirit of truth, comes, he will guide you into all truth. He will not speak on his own; he will speak only what he hears, and he will tell you what is yet to come (John 16: 7-13).

The gospel is a promise that God will (1) forgive our sins and (2) deal with us as he dealt with Jesus by bringing us and the entire cosmos to new life through death. But it is also a promise that the Holy Spirit will be the mode of God’s presence that will reveal those sins to us (“convict the world of guilt in regard to sin and righteousness and judgment” — John 16:8) and make us know both God’s righteousness in itself and the plan whereby God will make the world right.

Our mission as Christians is to become conscious participants in that plan, and it is predicated on “knowing” God in Christ Jesus. Not concepts about God and Christ and righteousness, but knowing God and righteousness in Christ Jesus.

I purposely emphasize the word “know” here because it underlines a kind of knowing that appears in a relationship of love, not merely the kind of knowledge that comes from understanding intellectually the biblical ideas and “believing” these ideas about forgiveness. The kind of knowing one possesses when one is “in love” is different than mere conceptual knowledge. We are talking, then, of participation in God’s Trinitarian life, not primarily knowing concepts about the Trinity but knowing God as Father, Son, and Spirit, a knowledge that impels the Christian to trust the promises of God and to try to do his or her part in revealing God’s plan in the world and to the world. Our Pentecostal brothers and sisters and the great mystics have something to teach us who live in our heads without the knowledge that comes from a love that rises in our gut.

Mission in Relation to the Gospel as Promise and the Forgiveness of Sin

Rather against my own will, over the past several years I have been persuaded that many Christians use the words “gospel” and “mission” as much to obfuscate as to clarify what they are talking about. What I mean to say is that many make mission into anything a church might want to do. While I will not attempt to document my charge of obfuscation or confusion, I believe that the words “mission” and “gospel” are used in so many contradictory ways that one would be hard pressed to derive from church practice a definition that is biblically satisfying. To me this is a far greater scandal than the institutional disunity of the church.

What I am driving at is that the word “gospel” is often still equated with a form of new teaching or a new law propagated by Jesus. Far be it from me to deny the importance of doing good works and trying to create a just world. Still, it is more faithful to the New Testament to see Christian mission as a response to having been gripped by the transforming power of the Spirit than as an obligation to implement a new teaching of Jesus. Catching that distinction makes all the difference.

The core New Testament meaning of the term gospel is clear. At the level of our earliest texts, the Pauline letters, the “good news” in the First Letter to the Thessalonians, for instance, revolves around the Thessalonians having received, in the power of the Spirit, confidence to turn to Jesus, trusting that God will raise the followers of Jesus, whom he has rescued from the wrath of God, just as he raised up Jesus (1 Thess 1: 2-10). The letter to the Romans is the longest and weightiest of Paul’s letters, but the word gospel boils down to good news about God’s power to save all who believe (Rom 1: 16-17). Faith itself is an act – aided by the Spirit giving testimony within – of placing total trust in Jesus as the Messiah (in the words of Romans 5: 1-5), an act wherein one experiences the consolation of being regenerated in the Spirit. Following the promptings of the Spirit, one experiences peace with God and a hope that does not disappoint made real by the Spirit.

In other words, the gospel is promise witnessed by the Spirit that God will act toward us as God has to Jesus, a promise, moreover, that the entire universe is being saved by God. In an historically and scientifically conscious age such as ours, the promise entails , as improbable as it may seem, the notion that world process in a 15-billion-year-old universe is in the hands of God. In that context we are invited by the Spirit to align ourselves with Jesus, to the point of following him through death to new life, becoming, as we join ourselves to the very logos (the [aboriginal] “plan”) of the universe, participants in a great eschatological venture (Rom 8: 18-30). The

Logos present at creation (Gen 1) becomes incarnate in Jesus, and the disciple who receives him dwells in the light of that Logos (John 1: 1-18).

Fundamental to the peace God gives in the Pauline version of the gospel (v.gr., 2 Thess 2: 7) is the reciprocal truth that, left to ourselves, humanity reverts to a state of rebellion repressing awareness of our true nature, missing the target or goal of life. Associating oneself with Christ, allowing the Spirit to illumine oneself to the nature of our plight as sinful, that is to say, quoting the old adage, being “convicted of ‘sin’,” (John 16: 8) is something different from the standard Western notion of recognizing that one has transgressed a law. The Greek words for sin in the New Testament are anomia (a state of being in lawless rebellion) and hamartia (being in a state of darkness and confusion about the purpose of life). The New Testament, in utilizing anomia and hamartia, takes over the Septuagint’s Greek translation of a variety of Hebrew terms that we render in the single and most inadequate English word “sin”. Bereft of the emotional weight and subtlety of both the Old and New Testament narratives, we run the risk of leading people astray if we repeat the formula that the gospel is a message about the forgiveness of sin. For the metaphor of God forgiving then becomes the metaphor of a judge who looks into our fundamentally good hearts and forgives us for the trivial offense of running a stop sign, so completely have the deeper dimensions of sin and its effects in the biblical language been reduced to transgressing a law. In our Freudian age, in addition, no one is really guilty of anything very serious, except perhaps not choosing one’s parents wisely, thus having deficient brain chemistry because of genetic bad luck.

Have we perhaps become victims of the modern Western assumption that there is little wrong with ourselves as individuals that a little psychotherapy or a modern pharmacological miracle won’t cure? Little wrong in our nation that a better brand of politics won’t cure? Little wrong in our world that a bit of tolerance or more just distribution of wealth won’t cure?

I bring this section to a close with two observations. First, when one takes seriously the message of the Hebrew and Christian Testaments, they bring into relief the plight of humanity on earth as living in anomia and hamartia, a state of rebellious blindness, being mistaken about our nature and goal, being lost in the dark, a dimension of the state of “original sin” that is not captured by the word “sin” in its common usage in English.

Second, gospel and mission are related. Christian mission revolves around helping human beings not just hear a message about Jesus. Rather, at its deepest level, if one reads the gospel

of the Apostle Paul with the pores of one’s heart and soul open, mission is our task of inviting others to participate in the reality of God-with-us revealed in the heart by the Spirit. Mission itself is a secular word, as we all know. Certainly one can trace mission to the Greek words apostellō, apostellethai, and apostolos (“to send,” “to be sent,” and “the one sent”), but the point I want to make as I conclude this section is that being sent into Christian mission is intrinsically related to the word gospel, euaggelion, “good news,” and that always has to do with Jesus as the one who delivers us from the effects of sin, both as hamartia (“being on the wrong track”) and anomia (“being in rebellion”). Forgiveness (charizomai, see Col 2:13; 2 Cor 10, 12, 13 and aphesis and aphienai in the synoptics and Acts, see Acts 3:19) has resonances of encountering the loving mercy of God who “blots out” and “remits” the “debts” (opheliēmata, see Mt 6:12) one piles up in the darkness of sin, even if one never intentionally does anything wrong.

Stanislas Lyonnet, S.J., (please forgive the use of “man/he” below when he speaks of humanity in an age before gender neutral language reached Rome) sums up the New Testament teaching on sin and forgiveness memorably when he concludes:

Man cannot be liberated from the tyranny of sin except by receiving a new dynamism, the life-giving Spirit, the Spirit of God, the only source of life. For sin was a power of death, dwelling in man, separating him from God and leading him to perdition. Christ liberated man from the slavery of sin through a mediation accomplished in a supreme act of obedience and of love, in which we participate in baptism and the Eucharist. Thus can the sinner pass from hate to love: Man’s mind is not only rectified, but re-ordained in love (Lyonnet and Sabourin 1972, 57).

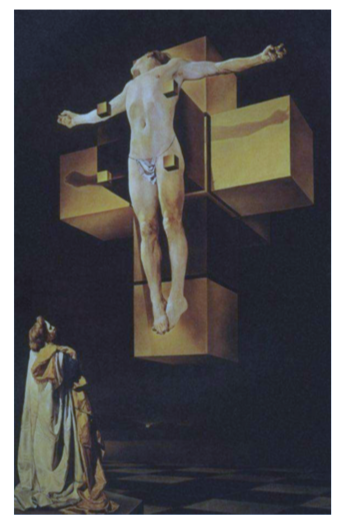

Lyonnet’s conclusion of a rigorous analysis of the Biblical teaching on sin in a liturgical key resonates in me, because the point of this paper is to propose that the concept and practice of mission reflect the richness of Scripture only if they reflect the life of churches that are zones of celebration of the gospel, or, as Catholics often put it, “celebration of the paschal mystery.” Liturgical life rooted in ancient practice can be a remedy for the tendency to reduce our understanding of Christ and his church to that of a problem solver conceived in mostly functional or instrumentalist terms. In the view being advanced here, the prime role of mission is that of “unveiling truth” as symbolic, liturgical action that complements and deepens verbal teaching and draws one deeper into the mystery of God’s promise than words alone can do.

Church as a Zone of Celebration of Gospel

I was once asked by Edward Schroeder, who more than any other has helped me to realize that the good news of the gospel is a promise about Christ’s role in the forgiveness of sin: “What do Catholics mean by the term ‘celebrate the paschal mystery’?” Like many seemingly straightforward questions, Ed’s question made me reconsider things that I had long assumed I understood but that, in fact, I had insufficiently reflected on. The more I reflected on it, the clearer it became that the fundamental meaning of “celebrate the paschal mystery” is “celebrate the gospel.” Both point to the context of mission as our part in God’s great promise. To make sense of the radicality of these terms, though, I need to go back to a bit of shared history that, in my opinion, has blown many Christians off course.

Beginning late in the last century, when Adolph von Harnack and friends began to apply the fruits of the wissenschaftlich historical method to sorting out what we knew reliably about early Christianity, a number of Catholic scholars were also using the new research methods with a different spirit. The enemy of getting to the pure gospel and purest early Christianity for Protestant scholars was encapsulated after Harnack in the term Frükatholizismus (“early Catholicism”), a plastic term that traces their discovery of pagan, Hellenistic elements, nascent clerical hierarchies and the encroachment of ecclesiastical powers in intertestamental times (see, for instance, Harnack, 1978, 190-207). By the mid-second century such Frükatholisch and Hellenistic deviations, they noted, had become nearly universal in Western Christianity. Needless to say, they did not approve of this early “Catholicizing.”

Catholic historians – and I refer especially to Benedictine monks who were examining the roots of Catholic liturgy – were also finding pagan, Hellenistic elements and Frükatholizismus, but because of their quite different view of the role of tradition, they came to a different conclusion. Instead of deviation, they detected the hand of the Holy Spirit helping the church unpack the surplus of meaning contained in the Scriptures and the ongoing life of the church in the Mediterranean world. They were enthralled by discovering the extraordinary degree to which Christians in the first century and onward were guided by the Spirit to subvert for Christian purposes the Hellenistic manner of celebrating the mysteries of the pagan cults. They saw the early church converting pagan ideas and customs to structure the celebration of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus as the mysterion of God’s deliverance of the human race from hamartia and anomia. While not using the language of “inculturation” in today’s missiological sense, they saw the employment of Hellenistic religious language and philosophy as translating Hebrew and Aramaic traditions of intertestamental Judaism wherein Second Temple worship brought Israel into living contact with Yahweh. (For a good summary of this material, see Wainright and Tucker 2006, 1- 130.)

Absent this sense of sin and participating existentially in deliverance from sin and coming into communion with Jesus as the logos of God incarnate, liturgy becomes a place for moral instruction. Jesus himself is demoted to the status of teacher like Siddhartha Gautama or Confucius, and mission becomes the foreign aid branch of the Western church, which is itself mainly the diminishing portion of Western culture that prays. Ultimately, faith becomes an act of subjective assent to doctrines emptied of the act of totally entrusting oneself to God the promiser, to the truth of whose word the Spirit testifies. Mission is no longer in its root sense a matter of being sent to make others aware that they are the heirs of God’s promise. It is, instead, doing good things for the suffering, which itself is a laudable thing that we should, no doubt, do more of. And within the churches, words like gospel and mission are used as warrants for whatever a group of undoubtedly sincere persons believes should be the church’s agenda. An agenda that then makes the church a pressure group pushing its program on the body politic.

Another Vision:

Liturgy as a Zone of Experience of Our Place within the Promise

It is no accident that the Apostle Paul uses mysterion (“mystery”) in ways that are consonant with Hellenistic mystery cult usages, subverting them so that Jesus becomes the heir to the promises of the Hebrew Testament and the revelation of their paradoxical fulfillment in the now and not yet soteriology of the Christian Testament. Growing up in Tarsus, Paul absorbed the language of such cults. In later Deutero-Pauline letters like Ephesians and Colossians, the use of the term mysterion subverts the Hellenistic mystery cults completely, so much so that in Ephesians 1: 9-10, the figure of Jesus as the Christ is the key to the entire fate of the universe and the cipher that reveals the good will of God toward creation. Scholars as different as Bruce Chilton (2004) and N. T. Wright (2005) recognize the depths of his understanding of Hellenistic culture, while pointing out how profoundly Paul uses this linguistic terminology to bring Jewish concepts to the Hellenistic world. In today’s language, Paul is the first great inculturationist.

This sense of liturgical celebration of the paschal mystery, I believe, is indispensable to adequate initial and ongoing formation of Christians, all of whom are called to be missionaries, whether we work abroad or cross-culturally or at home among members of our own culture.

Before going further, though, let me say that I realize I must tread carefully. Lutherans and Catholics have been arguing about things like the nature of the ordained ministry, sacraments, and especially the relationship of Word and Sacrament for nearly five centuries. Oceans of ink have been spilled analyzing how one can split hairs about what is the “real presence” of Christ in the Eucharist and the Eucharistic assembly. I realize that for Protestants, belief that the Roman Catholic way of centrally organizing global church life and teaching that God has endowed episcopal and papal leaders with the authority to declare what has been revealed and must be believed is a usurpation of an authority that belongs to the Scriptures and the Holy Spirit alone. Catholic liturgical life is viewed with equal suspicion for reasons I appreciate.

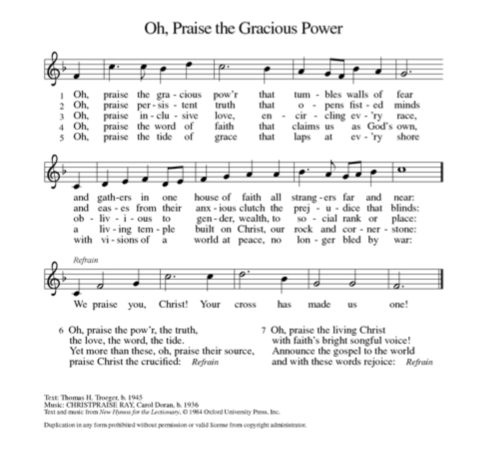

Arguments about such things need to be had on another day. I am trying here to make a narrower case. Namely, the case (1) that worship ought to be one of the key elements in congregational life — the principal zone of formation and transformation; and (2) that liturgy should center on a celebration of the paschal mysteries of our salvation as revelation of God’s promises, purposes, and means of acting in the world. We should be conservative in how we celebrate, lest in a desire to introduce things that will enliven the celebration we veil the centrality of Christ and the Spirit. Concretely, I want to suggest that making up worship as we go along is dangerous. What do I mean? For example, tailoring a wedding to the level of belief the young couple has for the gospel, making up vows that reflect sentimental love but very little the reality that marriage is God’s school for men and women to learn discipleship. Making a funeral a place for eulogizing the departed one, forgetting that it is the place where a community joins itself to the great cloud of witnesses past and present and celebrates the passage of a loved one from life to life, helping that community renew its hope in the promise being fulfilled in each member. Making Sunday morning worship a spectacle of sound and light on 60-inch flat screen panels, complete with Moses parting the Red Sea. Making seminary chapel exercises a demonstration project for students’ creativity rather than a place to learn how to function as a leader in a community whose living center is Christ, whom the Holy Spirit makes present in a special manner during the Eucharist.

Yes, traditional Catholic (or Lutheran or Reformed or Orthodox) orders of worship can be boring, but the problem of boredom at worship is really something about which my friend, the SVD liturgist Thomas Krosnicki, has said, “The problem of sterile Sunday worship is a problem of not doing anything during the week that raises one’s consciousness … not reading the scriptures, joining in deeper conversation with one’s fellow Christians , not spending time in family in the morning, at noon, and at night, praying and harmonizing one’s life with the Lord.” Such things one brings to liturgy and joins with Jesus in the renewal of his paschal mystery.

At risk of making a sweeping generalization, let me suggest that the single greatest weakness in Western Christianity since the early 19th century is equating religion with ethics and then making Sunday worship a time for instructing people on how to behave if one wishes to be faithful to Christ. We have moved this direction, I believe, because Kant’s critiques have made us recognize the limitations of human knowledge. We are wary of trying to talk about such things as eternal life, our place within the “grain of the universe” (see Hauerwas 2001), and God’s promises, because the “cultured despisers” of Christianity know such doctrines are untenable in a scientific age. Saying that what we are about in worship is celebrating the paschal mystery and giving thanks that we are part of it, well, it just seems too fanciful. Embarrassed by such metanarrative-based doctrines on the shape of creation and our hopes for its completion in God in a way foreshadowed in the resurrection, we retreat to what is safe – offering practical moral guidance rooted in the New Testament.

The most important criterion for genuine liturgy is not just how much or how little pomp is involved but whether it brings the worshiper to participate in the mysteries that are enshrined in God’s promises realized in Jesus. As far as the origins of complex worship ceremonies are concerned, the liturgical scholar Paul Bradshaw reminds anyone who wants to reconstruct the liturgy of the early church for today that almost every generalization is wrong (see Bradshaw, 2002 and 2004). Liturgies varied immensely in the first several centuries. They were different in Persia, Nubia, Ephesus, Mediterranean Gaul, or Rome and Ravenna. There is as much evidence, according to Bradshaw, for early liturgies that were complex as there is for later ones that were simple and vice versa. What is clear is that by the first half of the fourth century, the rites of worship were celebrated as various ways of participating in the paschal mystery in communion with one’s fellow Christians.

Rodney Stark (1996 and 2006) shows, conclusively I think, that it was the integrity of the new Christian communities and their steadfastness in love and service to one another in practical ways – caring for the victims of pestilence and burying the dead, for example – that turned the tide of pagan public opinion in favor of the Christians in the Roman Empire. Yes, such habits of service and love gave credibility to the missionary efforts of the new movement. And it is common for missiologists to say that if the church is to have similar success in our age, it needs to implement analogous programs of social welfare and to aid in the liberation of people in Latin America, Africa, and inner city United States. Agreeing that we should do all these things, I draw another conclusion about how the early church became what it was.

The lives of this cloud of witnesses in the early centuries were formed primarily within a liturgical context of celebrating the mysteries of Christ. Scripture was interpreted in the light of liturgical celebration, not principally in a scholar’s study. David Power believes this balance should be restored (see Power 2001, 47ff., 131ff.). Lives transformed in settings of community worship overflowed the boundaries of the liturgical assembly and did the sort of actions that Stark shows gave Christianity credibility in the first centuries.

My Question: In our own day, does renewal of mission need to return to celebrating the paschal mystery in ways that enable men and women to bring their entire lives to the liturgical act and participate in the paschal mystery of Christ who comes to meet them? In such celebration God takes over the schooling of the inner person, making that person fit to be God’s witness, putting on a “new self created to be like God in true righteousness and holiness” (Ephesians 4:24).

Celebration of the paschal mystery in early Christianity was an acknowledgment that the supremely most important events in history are those that surround the life, death and resurrection of Christ, the pattern of whose life is a revelation of the grain of the universe.

Christian ethics and missiology are based in the reality that, if we allow ourselves to be conformed to Christ, the Spirit will move us away from anomia and hamartia (Rom 8: 29; 12: 1- 2; Eph 3: 16-19) and we will experience the forgiveness of sin that leads us to gratitude to God for the fullness of life.

Only with some sort of renewal on these lines will our churches become zones of celebration that nurture the Christian missionary life in its fullness. Most followers of Christ will go into mission as husbands and wives, missioners in their families and local communities. Some will venture into foreign lands as evangelists and diggers of wells. But if we are to avoid the subjectivism and consumerism of contemporary life, the church must find ways to make their life worship in the spirit and truth of the paschal mystery.

Concluding Remarks

I began our time together reading a passage from Philippians in which Paul prayed for the community at Philippi. It is a prayer that is repeated in other words in Ephesians 3: 14-20:

For this reason I kneel before the Father, from whom his whole family in heaven and on earth derives its name. I pray that out of his glorious riches he may strengthen you with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith. And I pray that you, being rooted and established in love, may have power, together with all the saints, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge—that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God. Now to him who is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to his power that is at work within us, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, forever and ever! Amen.

It is this vision that rescues us from the anomia of living out of synch with the great symphony that is the universe struggling to become what it is meant to be. It is not a set of ideas or concepts. Rather, it is the ability to hear the deepest chords of the symphony of the universe. God’s forgiveness is not giving us a pass if we run a red light, it is the offering of a relationship that gives us new eyes to escape sin as hamartia, blindness to the path of becoming who we are meant to be in God’s plan for making the world right.

Most of all, it is a vision of realizing in our inmost being that God’s reconciling Spirit has made us one with God and all creation and then making that realization part of our way of living. It is a way of participating really, not just conceptually, in fashioning a life that is one with the grain of the universe. Participating in that mission transforms us, and it is that transformation that enables us to join in God’s mission in whatever state of life we find ourselves.

References:

Alberigo, Giuseppe, Peikle-P Joannou, Claudio Leonardi, and Paulo Prodi, eds.

1972 Conciliorum Oecumenicorum Decreta. Freiburg: Herder. “Decrees of Vatican Council I,” see esp. “Sessio IV, Constitutio dogmatica prima de ecclesia Christi,” pp. 787-92

Bevans, Stephen B., and Roger J. Schroeder

2004 Constants in Context. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books

Beverley, James A.

2008 Christianity Today (August): 50.

Bottum, Joseph

2008 “The Death of Protestant America: A Political Theory of the Protestant Mainline,” First Things (August/September): 23-33.

Bosch, David

1991 Transforming Mission. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books.

Bradshaw, Paul E.

2002 The Search for the Origins of Christian Worship: Sources and Methods for the Study of early Liturgy, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2004 Eucharistic Origins. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Casel, Odo.

1962 The Mystery of Christian Worship, and Other Writings. Westminster, MD: Newman Press.

Chilton, Bruce.

2004 Rabbi Paul: An Intellectual Biography. New York: Doubleday.

Cuénot, Claude.

1965 Teilhard de Chardin: A Biographical Study. Baltimore: Helicon.

Harnack, Alolf

1978 What Is Christianity? Translated by Thomas Bailey Saunders. Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith (orig. German ed., 1900).

Hauerwas, Stanley

2001 With the Grain of the Universe: The Church’s Witness and Natural Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press.

Ingraham, Barton

2008 Letters to the Editor, First Things (December): 8.

Lonergan, Bernard J. F.

1958 Insight. New York: Philosophical Library.

Lyonnet, Stanislaus and Léopold Sabourin

1970 Sin, Redemption, Sacrifice: A Biblical and Patristic Study. Rome: Biblical Institute Press.

O’Neill, Joseph

2009 “Touched by Evil,” A Review of Flannery by Brad Gouch (Boston: Little Brown). In The Atlantic Monthly (June).

Power, David

2001 “The Word of the Lord”: Liturgy’s Use of Scripture. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books.

Stark, Rodney

1996 The Rise of Christianity: A Sociologist Reconsiders History. Princeton, N.J.:Princeton University Press, 1996.

2006 Cities of God: The Real Story of How Christianity Became an Urban Movement and Conquered Rome. New York: HarperSanFrancisco.

Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre

1969 The Divine Milieu. New York: Harper & Row.

Theologians of the Society of St. Pius X

2001 The Problem of the Liturgical Reform. Kansas City MO: Angelus Press.

Wainright, Geoffrey and Karen B. Westerfield Tucker, editors

2006 The Oxford History of Christian Worship. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wright, N. T.

2005 Paul in Fresh Perspective. Minneapolis: Fortress.