Uniting the Concerns of Theology and Science

through the Lens of Luther’s Distinction between Law and Gospel

and in a Meta-Narrative of Stewardship

Steven C. Kuhl

I. Introduction: The conflict between Theology and Science is an opportunity to save Theology and Science from their respective ideological captivities, left and right.

1. Theology (properly understood as “claims about God”) and science (properly understood as “claims about the world”) dominate our life in the 21 Century. I can’t imagine a day going by without encountering claims of one kind or the other being made, here or there, in the routine of daily life: whether it be in the newspaper, on the TV, in the work place, in the home, in church, in a visit to the doctor, in conversation with strangers and friends. The world in which we live is at once, theological and scientific. Indeed, we can’t live without coming to terms with both these dimensions of life.

2. Even so, much of the time we live either, on the one hand, as though “never the twain shall meet,” as though theology and science are, as Paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould has called them, “nonoverlaping magisteria” (NOMA)1 or, on the other hand, as though the relationship of the two were easy and self-evident, that God is a benevolent, supreme being who has created a world that is good and intends my good. But just when we get comfortable in one or the other of these opinions about the world and God, then enters the so-called “war between theology and science” which wakes us from our dogmatic slumber.

3. While there are numerous fronts on which the war between theology and science is being waged, no front is more contentious than that being fought in the biological sciences with its desire to understand the origins and mechanisms of life in the universe. Therefore, I will arbitrary focus my discussion with that battle front in mind and as it relates to Christian Theology and its chief, ecumenically received sources and symbols, the Old and New Testaments. The extreme boundaries of this “battle front” are defined by the “Scientific Creationists” (and their more refined cousin, “Intelligent Design theorist”), on the one hand, and the “Philosophical Naturalists” or “Materialists,” on the other. What is striking about these two camps is their common assessment of “human reason,” understood as the ability to grasp reality as a continuous chain of causal events, i.e. instrumental reason. There is no inherent paradox in reality. Claims about God and claims about the world are fully adjudicated in the court of reason. Therefore, neither believes in anything like Gould’s “Nonoverlapping Magisteria.” The problem is that “reason” now appears to be a divide court. That true even though the civil courts have officially decided that Scientific Creationism and Intelligent Design are not purely scientific theories but religious ideas about the nature of the natural world that are outside the “magisterium” of the courts and out of place in publicly sponsored education. (By the way, I agree wholehearted with that verdict, and we can talk about it more later if you wish.)

4. When Scientific Creationists (including, Intelligent Design theorists) look at the created world, they see evidence of a natural world that is so complex and orderly (“irreducibly complex” is the term Michael Behe uses for it2) that there is only one logical conclusion: Someone who transcends this world created this world and predetermined its purpose. This world is the “creation” of an Intelligent Designer. This logical conclusion concerning the natural world confirms for them two essential points. First, it means that “modern science” is wrong to restrict itself to “methodological naturalism,”3 the idea that “science” by its very nature must restrict itself “to explaining the workings of the natural world without recourse to the supernatural.” Scientific Creationists believe that supernatural causes are as accessible to instrumental reason as natural ones and can be given scientific status. Second, it means that the message of the Bible, including its message about human origins and the purpose of life, morality, authority, etc., is scientifically sound. The Bible is the textbook of everything (for both theology and science, and all the domains of life, morality, politics, etc.) that is to be read literally. Reason and science, properly exercised, and the Biblical message, literally read, are one. Moreover, Creation Scientists and Intelligent Design Theorists do not deny “evolution” on a micro- level, the only level, by the way, on which evolution has been observed. Things change, even as the Bible attests. But they do deny evolution on a macro-level. The mechanisms of evolution as described by Darwin, they argue, even when synthesized with modern genetics (the so-called “modern synthesis” or “Neo-Darwinism” that emerged in the 1950s) cannot account for the origin of life or its present diversity. The meaning of the Biblical phrase that God created each species “according to its kind” is a scientific statement that refutes macro-evolution and common descent.

5. When Philosophical Naturalists (especially, people like Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett) look at the world they see something very different. To be sure, the biological world that has evolved is very complex: it even has aspects that are elegant, beautiful, and awe-inspiring to believers and non-believers in God alike. Nevertheless, the existence of that elegance is not the whole story, and if science is anything, it is open to being responsible for all the data, even those stubborn facts that mess up a nice hypothesis. The Creationists, they charge, do not look at all the data. The world is not simply the nice, neat, harmonious “creation” that Scientific Creationists make it out to be. First, on a purely technical level, there are a lot of “design flaws” and useless biological structures in various species that an “Intelligent Designer” would never have incorporated. Second, on a deeply emotional level, the preponderance of evidence for “natural selection,” a euphemism for the cruel term, “survival of the fittest,” as a dominate (though not the only) force behind evolution in the natural, biological world, along with the problem of pain and suffering, argues not for a world created by and governed by a beneficent deity, but for something else. For the Philosophical Naturalist, theodicy (the righteousness of God) is a key issue and atheism is not simply a reasonable answer, but a pious one. The methodological naturalism that informs modern science begs also, they insist, philosophical naturalism. Nature is all there is. For, if God is the author of this cut-throat creation and, therefore, cut-throat himself, why should he be worshipped? Hasn’t religion been the great inspiration of much of the world’s chosen violence? Even more important, if there is no God, if this world is the result of natural, random change, then we human beings who are the lucky by-product of nature must make use of our evolutionary good fortune (our possession of wisdom, knowledge, compassion, justice, etc.) and use it now to direct evolution and nature’s future. For most of its evolutionary history, humanity looked for a God to rescue it from its problems. The truth is, argues the Philosophical Naturalist, we have to do it ourselves. 4

6. As you can see this is one contentious fight between two Grand Narratives ostensibly designed to make the most of the scientific data and the phenomenon of religion. In general, Scientific Creationists believe their scientific evidence confirms the old Biblical Creation Narrative as positive history and scientifically correct; Philosophical Naturalists believe their scientific evidence confirms the new Enlightenment Narrative as represented by David Hume, Friedrich Feuerbach and the like that sees religion and belief in God as an illusion whose evolutionary function is quite understandable but now passé. I think both are wrong, not on modern scientific grounds, rooted in methodological naturalism, but on theological grounds, rooted in a popular but fallacious doctrine of God. The Scientific Creationists do not adequately represent the God of the Biblical Narrative (which I will stand by) nor do the Philosophical Naturalists properly represent the theological challenge of David Hume and the Enlightenment (which I also find compelling). Indeed, both parties are endangering the role of science by holding it captive to their respective ideologies. By so doing they refuse to let science do its job of learning more about the nature of the created world by bracketing all religious and metaphysical question.

7. Interestingly, both the Scientific Creationists and the Philosophical Naturalists read the Bible through the same hermeneutical or interpretive key—i.e., literally, as though it is a straight forward scientific account of the world and that God’s relation to and activity within this world is simple and monolithic. Specifically, they operate with the same monolithic view of God, as that one who is unambiguously benevolent and whose existence de facto guarantees consolation and meaning regardless of circumstance.5 The difference is that one believes in this God and one doesn’t. Here is my point. That is not the biblical God and that hermeneutical key will not unlock the meaning of Scripture or life in this world.

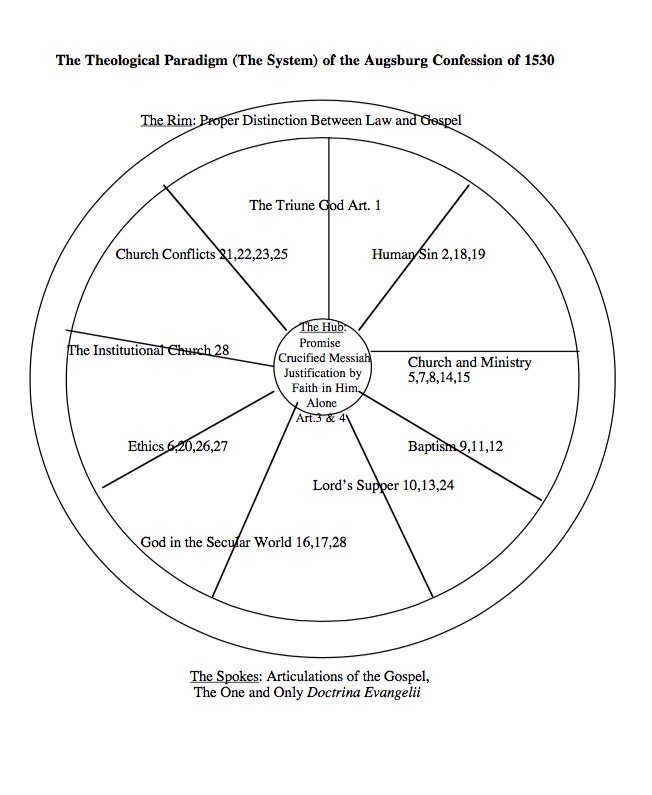

8. In this paper, I argue that the hermeneutical key for understanding the Biblical message about God and God’s relation to the world today is the law-gospel hermeneutic, as Luther (re)discovered it from reading Paul and as Ed Schroeder described it in the Opening Address of this Conference. Calling this key a hermeneutic and not a doctrine or loci or topic is important. A hermeneutic is not simply one concept or doctrine or topic among many but a meta-concept for organizes everything. The basic premise of this hermeneutical key is that God’s being and action in the world is twofold and that those actions relate paradoxically: On the one hand, God’s wrath (or law) is executed/revealed on all ungodliness in a hidden, obscure manner through the things that are created (the mask of God as Luther called it), whether they believe it or not (Romans 1:18-25). On the other hand, God’s mercy (or gospel) is executed/revealed for the ungodly in the world in a revealed, clear manner through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ to those who believe in him (cf. Romans 5:6-11). Distinguishing between these two paradoxically related kinds of activities and beings of God (variously described as the distinction between law and gospel, old creation and new creation, creation and redemption, God hidden and revealed, death and life, judgment and promise) is the key to both interpreting Scripture and living meaningfully in the world. It is with this hermeneutic in mind that I will now turn to the Creation and Fall stories in Genesis and show how this Great Narrative need not be a stumbling block in theology and science debate, but real help to overcome the ideological captivity that Scientific Creationists and Philosophical Naturalists would impose on science.

II. God, Creation, and the Human Steward: Genesis 1 and 2.6

9. The Great Narratives of Creation in Genesis 1 and 2 are statements of faith. More pointedly, they are “crossings.” They are the work of some unknown story tellers and compiler(s) who attempted over a long period of time to relate or cross the “faith of Israel” with the popular “science” or understanding of the world as it exists. Indeed, as modern, historical critical scholarship has taught us, the popular “science” of the day did not simply emerge from within the faith community of Israel itself but from their engagement with the ideas of other peoples and powers. Key among these peoples was the great and powerful kingdoms of Egypt and Babylon, who were both the intellectual and cultural wonders of their day and Israel’s greatest nemesis. The so-called wet (Priestly) creation story of Genesis 1 (which may have had Babylonian myths of origins in mind) and the so-called dry creation story of Genesis 2 (which may have had Egyptian myths of origin in mind) are crossings of two very different accounts of life as it is from peoples that Israel encountered in its daily life—specifically, a life in bondage. Two important implications emerge from this. First, we have access to the faith of Israel or the Word of God only in these crossings form. Distinguishing, then, what is normative in the text and what is conditional is essential to understanding them. Comparing the texts can be very helpful in this regard. Second, the ongoing process of crossing the “faith of Israel” (by which I mean to include its Christian developments) with new understandings of the world, like modern science presents, is not therefore contrary to the biblical concern but integral to it. Now let us turn to the text of Genesis 1 and 2 themselves. I’m going to assume that you all have a basic knowledge of them.

10. “And God Said”—Creatio Ex Nihilo. First, what is most striking about the two Biblical Accounts of Creation is now “un-mythical” they are in nature—poetic and metaphorical, to be sure, but not mythical. Indeed, their account might best be described as an existential account of creation, creation as they experience it day to day. In that sense they are not so much a description of the “origins” of the Created World, but its “ground of being,” to us Tillich’s term. They take the world as they observe it as a fact, as a relational whole, intimately interconnected, and assert that it is the good creation of God. To be sure, the accounts are not “scientific” in the modern sense of the term. They do not seek to explain natural processes or there origin with any kind of scientific sophistication. But they do honor the created world as God does—as “good.” In effect, there is only one teaching concerning the origins or grounds of the created world asserted in these biblical texts: namely, the idea of creatio ex nihilo, that God simply called the world into being “out of nothing.” Nothing, too philosophical should be made out the imagery of God’s speaking (the “and God said”) other than that God creates without dependence on anything else, and that nothing exists—even now—unless God brings it into being. It is a way of describing God’s transcendence or otherness from the Creation. To be sure, in so far as the claim that God creates ex nihilo is also a claim about the natural world, it is a claim that is subject to scientific investigation. Here the interests of theology and science overlap. The present day scientific consensus about the BIG GANG THEORY (a theory that it is certainly compatible with, though does not prove, an absolute “beginning” to the Creation) is certainly compatible with creation ex nihilo, even though it would never have crossed the minds of the biblical writers. As I said, the Big Bang Theory doesn’t prove the existence of God. Scientists cannot get “behind” the bang, at least not yet, and if they do they will never get to God, who transcends Creation.7 At least, that is the “faith of Israel.” Any “god” that is “scientifically” graspable by humanity, in the modern sense of the term, is not the God of Israel. Nevertheless, that modern discovery of the Big Bang is no small matter. One of the big issues in the Middle Ages was the stark contradiction between Aristotle’s notion of the world as eternal (Aristotle’s natural philosophy was the cutting-edge “science” of the time) and the Biblical notion of the world as temporal. What this proves, if anything, is that Aristotle’s Natural Philosophy isn’t “science” in the modern sense of the term, but a philosophical/religious assumption masquerading as such.

11. “And God Blessed Them … Be Fruitful and Multiply”—Creatio Continua. Second, the biblical faith is not deistic. God creates ex nihilo, not only “in the beginning,” but in every moment. Connected with the idea of creation ex nihilo, therefore, is the idea of creatio continua. The God who transcends the Creation, and who is totally other from the Creation, is also the God who is intimately at work in and through the Creation. What the biblical writers observe is a fruitful creation, a continuing creation. That fact is not a sign of the autonomy of the Creation from God but God’s on-going creative activity in and through the things that are created, what the text calls “blessing.” The fruitful operations of nature as they are observed by the eyes of faith do not conflict or compete with the idea of God as Creator but confirm it. Again, the text offers no “scientific” explanations of the fruitfulness of creation, in the modern sense of the term. That, the natural processes of world, it leaves as a open question, free for human investigation. But more on that later.

12. “In the Image of God”—Humanity as the Creation’s Representative before God and God’s Steward of the Creation. One of the most contentious features of the Theology-Science debate is the nature and status of the human creature, not only vis-à-vis the rest of creation but also God. A central issue is the interpretation the phrase “the image of God.” Because the phrase is a hapax legomenon, a phrase that only occurs once in the biblical text, its meaning must be carefully delineated in light of what else the narratives of creation say about humanity. First of all, the term most definitely does not mean anything like that which the Gnostics (ancient or modern) say about humanity, namely, that humanity has a “spark” or a part of the divine within. Humanity is totally and thoroughly a creature whose existence, like all creatures, is depended totally on God and on God’s placement of humanity within the Creation as an organic whole. Not only does the very Hebrew word for humanity make this clear, adam means earthling, one who is of the earth8, but the description of the creation of humanity in Genesis 2 creation account also makes this clear. There is no essential difference in the way humanity is created from that of the rest of the Creation, specifically, the animal world. Concerning the creation of humanity, I quote: “the Lord God formed adam from the dust of the ground (adama), and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the human became a living being (nephesh)” (Genesis 2:7). Now concerning the creation of the animal world, I quote: “out of the ground (adama) God formed every animal … and whatever the man (adam) called every living being (nephesh), that was its name” (Genesis 2:20). Humanity together with all living animals is called “nephesh,” “living being.” Concerning the phrase “breath of life,” this is the term Genesis 1:30 also uses to describe animals in general, anything that has breaths. It is not a unique thing like the Greek notion of the “soul,” for example. In short, the text is existential in outlook. The idea that humanity was created in the “image of God,” means that humanity stands in “correspondence” with God, to use the word that Athanasius used in his “On the Incarnation of the Word.” Humanity is that part of creation that is aware of itself as creature (self-consciousness). As such, humanity is beholden to and responsible to God, representing all of the Creation before God. Therefore, as the human fairs before God, so fairs the whole creation. This is Paul’s assumption in Romans 8:19-25 and why the redemption of humanity is central to the redemption of the whole Creation.

13. But there is more to this concept of the “image of God.” Humanity, as that creature who lives in correspondence with God, is also God’s designated steward of the Creation. This is a central affirmation of the texts as expressed in Genesis 1:26, when it states that humanity has been given “dominion over” all living things, and in Genesis 2:15, when it asserts that humanity is created to “till [the garden] and keep it.” “Dominion over” is to serve not the exploitation, but the care of the Creation. Accordingly, in this concept resides what I would call the “scientific imperative” given to humanity by God, including the modern sense of the term. True, the Biblical Narratives on Creation do not give us a scientific account of Creation or how this imperative arose, but they do assert as a matter of fact the capacity on the part of humanity to “do science,” to grow in our understanding or comprehension of the created world, and to do so for the sake of our calling to be good stewards of it. This notion of dominance, I would argue, is compatible with modern science’s insistence on “methodological naturalism,” of restricting its investigation to the natural world. Humanity can understand, control and safely probe only that which it has dominion over—and that is the natural world—and it exercises dominion appropriately by giving due respect to and care for the delicate created nature of the Creation.

14. The nascent development of this capacity to understand and “till” the earth and participate in its fruitfulness, the practice of stewardship, is already evident in the text. When the biblical account recognizes that all creation, on the one hand, consist of “dust,” and yet, on the other hand, exists each according to its own “kind,” defined by its capacity to be fruitful and multiply—they are simply engaging in the age old practice of taxonomy. The text makes no scientific claim in the modern sense of the term about how the kinds emerged or about the eternal stability or instability of the “kinds.” Indeed, the idea that “kind” here means “special creation,” i.e., that the species emerged on the scene by fiat, is a Medieval interpretation of the text based on correlating it with the assumption of Aristotle about the stability and, hence, the know-ability of the world in terms of natural law. Aristotle argued this against the Greek atomists who said the world is in constant flux and hence ultimately, unknowable and unpredictable. Aristotle, the first champion of natural philosophy, rejected both the idea that world is created by God and that it is in flux or evolving. The Order of Nature is simply eternal, constant, changeless in essence because of the eternal forms that give them order, at least at the level of species or kinds.9 The church, wanting to affirm the “scientific” potential in Aristotle’s thought, justified it by reference to the Genesis notion of “kind.”

15. While Genesis is adamant about humanities dominion over the Creation, it is equally as adamant about God’s dominion over humanity. Accordingly, God is always in control and as such always allusive, mysterious, unfathomable, and incomprehensible, except on God’s own terms, as God reveals God’ self to humanity. In giving humanity dominion over the Creation, God does not relinquish God’s own dominion over the Creation or over humanity, but authorizes humanity, as a steward, to participate in God’s creative enterprise. While humanity’s basic relationship to the Creation is rooted in its ability to know and control the natural world, its relation to God is rooted in its ability to trust God and to rely on God always. Strictly speaking “to know” something is to be able to make it an object of control; “to trust” someone is to be totally dependent on their trustworthiness. This defines the fundamental difference between theology and science in the modern sense of terms: Theology seeks to increase faith in God and science seeks to increase knowledge of the Creation. While on the one hand, they are very different kinds of enterprises, on the other, they find their unity in the idea of Humanity as God’s steward of God’s Creation. As God’s steward of Creation, humanity stands between God and the Creation, constantly looking (metaphorically speaking) in two directions: upwards towards the God from whom it receives dominion and to whom it is accountable; and downwards to the Creation of which it is a part and over which it is to be steward and care taker.

16. “It is good”—Freedom not Telos Marks the Essence of Creation. Significantly, the biblical account as an existential account of Creation presupposes no blue print to be follow or no preconceived goal or telos to be achieved. This is in stark contrasts to the Creation Myths of Israel’s neighbors who told their story of creation/origins in such a way as to justify their political and social order as the goal of the divine–ancient versions, perhaps, of Hegel’s own philosophy of history or America’s doctrine of Manifest Destiny. In essence, their telling of Creation was deeply ideologically laden. The Creation as described in Genesis is at root a “natural order,” not a “political order,” and it is marked by freedom and joy. The “it is good” which punctuates every level of the natural ordering of creation in Genesis 1 is an aesthetic judgment on the part of God. It is a stretch, therefore, even to say that God created a “moral order,” if by “moral” we mean a deontological or legal system of ruling through “oughts.” The world is a natural order that has no “need” at this point for criticism, no experience of God’s wrath or anger that is inherent in the use of the term “law” in its strict theological sense and in the hermeneutical notion of the distinction between law and gospel. This is also true of the “it is not good” concerning the personal aloneness of adam (Genesis 2:18). That, too, is an aesthetic judgment that is intent on showing the meaning of humanity’s differentiation into male and female. First, sexuality is that quality of the creature that allows it to participate in God’s continuing creation of itself, its kind. As such, at its most basic level Creation is a relational reality. This is true for humanity, too. Humanity like all the other “kinds” of creatures is by nature a relational “kind,” male and female, even as Genesis 1:27 asserts when it says “in the image of God he created them/male and female he created them.” Second, and more importantly, there is no sense of domination of one gender over the other, no sense of gender roles defined in social, political or economic terms. Humanity isn’t male or female, but male- and-female, a kind defined by partnership and, therefore, the quintessential expression of humanity is marriage as a natural phenomenon, as a bodily phenomenon, where the “two become one flesh.” Wherever, men and women come together in a natural, bodily way there is marriage, there is humanity, revealed as a relational reality, as a partnership of equals who complement one another in living out God’s call to be stewards of the Creation.

17. Given the fact that the Creation is a “natural order,” is it any wonder that when modern scientists look at the natural world, including the human world, it sees no defined end goal, no grand purpose, only the continual, free interaction of natural processes and responses over time? There is none! If we can lay aside our ideological lenses for a moment and look at the Creation accounts afresh, what we see is a dynamic, natural order, existing as an organic whole, marked by freedom and joy. There are no preconceived notions of progress, no grand goals to strive for, no operating rules given as to what faithful stewardship should look like. To be sure, humanity is free to organize its life politically, to nurture itself intellectually, to express itself artistically, to develop the fruitfulness of the Creation economically, and to worship (correspond with) God honestly, openly, without fear. Indeed, given the way humanity is created, one cannot imagine humanity doing anything but these kinds of things as it lives out its calling to be God’s steward of God’s Creation—for such stewardship exercised in freedom is its joy.

III. God, the Fall, the Law, and the Human Steward—Genesis 3

18. The “faith of Israel” is not naïve. It is quite aware that the world as it now exists is not simply the “good” creation of God, although traces of that aesthetic judgment still is evident, and evident to believers and non-believers alike. No. Something is awry, and no amount of ideological manipulation can cover over that fact. That, too, is evident to believer and nonbeliever alike. Existentially speaking, the freedom, faith/trust, and joy that marked the Creation “in the beginning” has given way to compulsion, fear/suspicion, and despair; and no creature is more aware of that fact than humanity. Why? Because humanity is deeply implicated in this change of condition. Therefore, on the heels of the Creation story comes the story of the “Fall,” as Augustine first called it.

19. This condition is often discussed under the category of “the problem [or origin] of evil” and coming to terms intellectually and personally with the fact of this fallen state of affairs is an inescapable part of the human condition. Every culture, every religion, every philosophy wrestles with it because every human being encounters it in the course of daily living. One predominant way of dealing with this fact is dualism: positing this existential awareness to the clash of two metaphysical principles (good and evil, light and darkness) with humanity as the victim caught in between. That essentially was the intellectual strategy of the Babylonians in Israel’s day and has been an essential strategy of religion and cultures down through the ages, whether in the form of Marcionism, Manichaeanism or all manner of Gnosticism and New Age Spirituality ancient and modern. Another dominate approach has been Philosophical Materialism, which denies the existence of evil as an illusion rooted in a misunderstanding of the natural processes. Neither of these, as we will see, is the outlook of the “faith of Israel. True, evil is a thoroughly “natural” phenomenon, it is nature—specifically, natures steward—turned away from, or better turned, against its Creator and Lord, but it isn’t merely material. It is also God turned against nature—specifically, nature’s recalcitrant steward—and that makes it a spiritual phenomenon as well, one marked by wrath, anger. The only way to get at this dynamic is through narrative. So let us now turn now to Genesis 3 and the way the “faith of Israel” deals with it.

20. What is most incredible about the Fall Narrative, given the mythical predilections of its neighbors and captors, is how un-mythical it is. To be sure, like the Creation Narratives, it is filled with symbolism and metaphor, but it is not mythical. Rather, it, too, is existential in nature, giving an account of the depth dimension of “evil” and “sin” in daily life now. It is not a scientific account, in the modern sense of the term, of the origins or evil but a theological account. Why? Because the nature of “evil,” like the nature of the Creation, is not purely natural, though it has naturalist elements to it, but it is also theological, it has to do with the present relationship that exist between the God and God’s steward. It is the theological component of humanity’s struggle with sin, death, fear, suffering, and conflict that the text seeks to illuminate. Therefore, like Creation, it is talking about a mystery. Mystery here does not primarily refer to that which is unknown, but that which is not under our control, not in the reach of our instrumental powers to reason, that which is beyond our grasp what but God discloses it to us, because the reality of evil is intimately wrapped up in the reality of God.

“Did God Say…?”—The Mystery of Evil and Mistrust of God (Genesis 3:1-7)

21. Significantly, the Fall Narrative begins with the description a “creature” and not a metaphysical concept or mythical being. That creature is a serpent who is described as being “more crafty than other wild animal the Lord God had made” (Genesis 3:1) and who is the symbolic nemesis who tempts humanity to fall away from God. While biblical scholarship is divided on how to interpret this passage, I take it to be a symbol of the way evil (understood as whatever is in opposition to God) works. This, then, is not a mythical tale of the origin of evil. That remains forever a mystery. Rather, it is a phenomenology of evil, a narrative description of how evil works at a deep level—at the level of the human heart and at the level of humanity’s relation to God. Moreover, the serpent is a highly familiar symbol of the age. The serpent itself is a symbol of wisdom, and historically, of Egypt—one of the most ancient, powerful, wise, and sophisticated cultures the world had ever known until then—and also Israel’s major nemesis! Therefore, in one sense the text has something of a polemical edge to it. But it is not ideological; rather, it is simply illustrative. For it is not written to justify the State or Kingdom of Israel vis- à-vis Egypt or any other nation, but to confess the state or condition of humanity in general (Israel included) as implicated before God for the evil that is in the world. The whole of human history is marked by this condition.

22. The nature of evil is complex but Genesis 3 seeks to rendered it accessible through a deceptively simple narrative form: the first half of the Narrative (verses 1-7) being a phenomenological examination of temptation and fall and the second half (verse 8-24) being a theological description God’s relationship to fallen humanity. The essence of evil is rooted in doubt (or disbelief), not about God’s existence, but about God’s Word and humanity’s call to be God’s steward.10 The Genesis narrative for describing this is clear. Humanity knows God’s Word, the question is do they trust it? Was God keeping humanity down by designating them as steward and by instructing them not to eat of the symbolic “tree of the knowledge of good and evil”? Or, was God keeping humanity safe and giving them what they needed, God’s self as protector and guide? The serpent (symbol of the wisdom of this world) asserts the former. Humanity believes the serpent and eats, holding onto the serpent’s promise that they will be like God, meaning, that they will call the shots on what is good and what is evil (Genesis 3:5), no longer existing as mere stewards but as lords themselves of their life and of the Creation. Evil or sin, then, is rooted in humanity’s attempt at a coup d’etat of sorts over God. It is the breaking of the created order of things at its most critical point: the relationship between of God and God’s designated steward of Creation. Because humanity represents the Creation to God, humanity is also, we noted, the point at which the Creation becomes aware of itself as Creation, the consequences of this break reverberates throughout the Creation itself, as Genesis 3:14-19 asserts. This broken order is what Augustine and Luther mean when they describe the human condition of sin (the classic notion of original sin) as humanity “turned away from God” and “turned in on it’s self,” respectively. In its heart, humanity puts itself in the place of God. But, as the text also makes clear, the serpent’s promise doesn’t pan out. That’s because it is based on a lie about reality as God creates it. Accordingly, rather than self-confidence, the human creature is filled with a deep seated sense of meaninglessness and shame (symbolized in nakedness), to which the only apparent solution is self-deception, the illusory attempt “cover up” the truth with something of their own making (Genesis 3:7).

“What is this that you have done?”—The Law as God’s critical Response to Sin (Genesis 3:8-24)

23. But that’s not the whole story. The Fall Narrative is not only about humanity’s changed approach to God, but God’s changed approach toward humanity—and that is what Genesis 3:8- 24 is all about. Attending to the sequence of the drama is crucial to the meaning of the text. Remember, up to this moment the Creation Narratives assumed a very “natural” correspondence between God and humanity as integral to the created order of things. Now God is depicted as walking through the garden at the time of the evening breeze; no doubt to converse with his steward. But now God notices that something is awry. The steward is hiding from God. The free, joyful, open correspondence is gone. What is significant is that God will not relinquish his Creation to the rebel stewards. The spiritual condition that humanity now finds itself in after the Fall is not that God is absent, that’s what the hiding tried to accomplish. On the contrary, God is quite present, but present now as critic, as the questioning judge toward a recalcitrant steward. The series of questions that God delivers at humanity and their incriminating answers are like a scene out of “Law and Order,” including the defendants turning on one another in a desperate, illusory, last ditch effort to save themselves.

24. Luther, in his Genesis Commentary, notes the irony in this passage. The evening breeze which before the fall was a comforting sign of God’s presence has now become a threatening sign of that same God, evoking fear (Genesis 3:10) like those things that go thump in the night. Now permeating the Creation is not only God’s word of blessing, which sustains the natural order in its fruitfulness, but God’s word of criticism and its corresponding curse that affects not only the human steward but everything the steward touches (Genesis 3:14-24). As the steward of the Creation fairs, so fairs the whole Creation (Cf. Romans 8:19-23). This critical dimension that is now introduced by God into the order of things because of sin is the notion of “law” as Luther’s law-gospel hermeneutic uses the term. Significantly, after sin, humanity not only continues to participate in the creative processes of God as steward, but also participates in the critical processes of God. The interlacing of these two processes, the creative and the critical, now informs every aspect of humanity’s vocation as God’s fallen steward of the Creation and creates a world of profound paradox. In so far as the critical process exposes sin and carries out the death of every steward as a sinner, we have what Luther calls the theological function of the law. In so far as this critical process creates sufficient fear to restrains sin and compel cooperation with the creative processes of God, we have what Luther calls the civil function of the law.11

25. Of course, this theologically laden concept of law is not unique to Luther. The reality of law as that which “makes sin known,” as Paul defines it, or that which “always accuses” (lex semper accusat) as the Apology to the Augsburg Confession describes it, permeates the Old and New Testaments, becoming especially focused in Paul as the counterpoint to the gospel, and has been a crucial datum for doing law-gospel theology throughout the ages, in such a line of notables, Irenaeus (against the Gnostics), Augustine (against the Pelagianists), Luther (against , Kierkegaard (against the Hegelian Systemizers), Walther (against Schmucker and the Definite Platform12), Bonhoeffer (against the pseudo-Lutherans), Elert (against both Schliermacher and Barth), to name a few, though the line may be a thin one. It is significant to note that this notion of law is not positive law. It is not some divinely, preconceived, a-historical list of “dos” and “don’ts” that God prescribes regardless of context—although at any instance they certainly do appear in concrete, commandment form as Bonhoeffer was wont to emphasize, just as they appear here is Genesis. Rather, like the “it is good” of the Creation, this notion of Law is God’s living, evolving, responding critique of the ongoing engagement of God, humanity and the rest of Creation.

26. This reading of the Genesis account is significant for the present engagement between theology and science. Recall the charge that the Philosophical Naturalists made against the doctrine of God of the Scientific Creationists. If there is a God, then why is there such a pervasive sense of meaninglessness in the world? The short answer can now be given: Because of sin and God’s judgment, God’s anger, upon it. God does not exist, after sin, as that unambiguously benevolent Someone whose existence de facto guarantees consolation and meaning regardless of circumstance. With Paul, the “faith of Israel” knows God as that good Creator and Lord of all who is humanity’s critic, intent on driving every human being out of its ideological hiding place and ridding it of its illusion of righteousness, so as to face the reality of sin. And if people will not face that reality in their consciences, they will face it in the flesh. This, theologically, is the meaning of death, quite apart from all the physiological elements that may coincide with it.

27. Note: Genesis is clear that science (especially, in the modern sense of the term, as learning more about the natural world for the sake of being good stewards of it) still remains a key intellectual and practical part of the human calling to till the earth, even after the Fall. God doesn’t simply pull the plug instantly on the Creation. That’s because God wants also to redeem this Creation, as the Flood Narratives of Genesis 6-10 suggests and the whole history of Israel attests. But more on that later. Nevertheless, the scientific imperative is frustrated and deeply complicated by the reality of sin. Not only is it frustrated when ideologues pervert and subvert the scientific enterprise to seek their own selfish, twisted ends (Eugenics and Social Darwinism as extreme cases for example), but also when God refuses to bless the fruitfulness of Creation to frustrate humanity’s sinful designs.

III. God, Christ, and the Redemption of Creation—Romans 8:19-18-25

28. I hope it is clear by now that theology and science are not opposed to each other when properly understood. Science proper is not called upon to investigate God, but the natural world for the sake of humanity’s call to be God’s stewards of that world. By contrast Theology proper is not called to advance our knowledge of the natural world but attend to the Word of nature’s Creator/owner/Lord. Humanity as God’s steward of the Creation is a creature that lives by looking in two directions: upwards to its Creator and Lord and downwards to the Creation it has been called to tend. They are not competing forms of knowledge but distinct, autonomous, complementary activities that find their unity in the human vocation of stewardship.

29. But as we have also seen, the human call to be God’s steward is complicated by sin and God’s law, given so “that every mouth may be silenced, and the whole world may be held accountable to God” (Romans 3:19). Sin, therefore, cuts two ways, having ramifications that are both spiritual ad material. Not only does the Fall story make this clear in the “curse” that now resides on the Creation because of humanity, but our ongoing, present human experience still attests to this fact. The advance of scientific knowledge—and the increased control it has given us over all kinds of natural processes—has not only revealed the fruitful potential of the Creation, but it has also revealed the fragility and vulnerability of the Creation in the hands of a presumptuous steward that is “turned in on itself,” that is, more interested in exploitation than cultivation.

30. In light of this fact, it is no wonder that Christian theology historically places emphasis on one other aspect of God’s activity in the world: “the redemption” of the whole Creation through the redemption of the human steward. This concern for the redemption of the world is the what “the gospel,” in Luther’s law-gospel hermeneutic, is all about. The biblical God is the God who acts in history Creator, Critic and Redeemer. Creation is the presupposition of law and gospel, which knows of Creation as under God’s judgment and in need of God’s redemption. With regard to the “problem of evil,” then, you might say that there at least two problems: the problem of origins, knowing exactly why and how it emerged in the midst of God’s good Creation, and the problem of solutions, how it is overcome. While Christian theology is very modest (finally pleading, we don’t know) concerning the issue of evil’s origins (theologically and scientific), it has been very bold with regard to the issue of evil’s solutions. God has acted in the world to bring forth salvation, justification, reconciliation, redemption to the broken Creation (the images are legion) through the cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ. One passage in Paul is especially telling with regard to the linkage of redemption of the whole Creation to that of the human steward of Creation, Romans 8:18-25. It is worth quoting here at length.

I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labour pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.

31. Several things are worthy of note. First. The whole creation is “subject to futility,” emptiness, meaninglessness and “subject to decay” not because of what the non-human part of Creation did, but because of the recalcitrance of its human steward. The whole Creation is caught up in the God-human conflict, the Fall, the falling out between God and God’s steward, that we discussed above at length. Second. Creation is not without hope, however, that hope is linked to the “revealing of the children of God,” that is, to humanity redeemed by participation in God’s saving act in Jesus Christ, the concern the dominates Paul’s Romans and which is labeled as justification (the participation in God’s act of making things right) by faith. Third. The principle as the human steward fairs before God so the whole creation fairs is key here because there is no absolute divide between anthropology and ecology, humanity and the Creation. The Creation is an organic whole. However, how the human steward fairs before God is the subject of theology proper, because it is the root problem that afflicts life as we experience it. Fourth. As Ed Schroeder noted in his keynote address, drawing on the thought of Bob Bertram, all Christian theology, therefore is ultimately rooted in Christian soteriology, the redemption of the Fallen world, just, as we might say, that all medicine is ultimate linked to heath. Distinguishing, the problem—the world under judgment—and the solution—the world united to Christ—informs every aspect of life, including that al1-pervasive aspect of life in this world called science, for the sake of the salvation of all.

32. At the beginning of this paper, I identified the two camps at the center of maelstrom in the public conflict being waged between theology, so-called, and science, so-called: the Scientific Creationists and Philosophical Naturalists. It should now be clear that the war is fueled by a false understanding of both theology and science to the detriment of both and to the demise of our stewardship of this Creation. Theology and science are two dimensions of our human vocation to be God’s steward of God’s Creation. Theology proper looks “up” to God, who, one the one hand, executes judgment (law proper) on the Fallen world, a judgment hidden in the conflicts and struggles of daily (Fallen) life, and, yet, who, on the other hands, promises to overrule that judgment gospel (proper), bringing the promise of new life for the whole Creation through participation in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ (gospel). This two-fold character of God’s activity in the world (as law and gospel) is the hermeneutical or interpretive key (the method, so to speak) to reading both scripture and daily life from a theological point of view. Science, by contrast, looks “down” to the created world and employs its God-given dominion over the Creation in order to understand nature’s processes better for the sake of fruitfulness and integrity of the whole Creation. Its method can rightly be described as methodological naturalism. It is not interested in investing God per se—God en se is out of the reach of scientific investigation—but the Creation, as God created it, on its own terms, according to its “kind.” Science, in order to be science, must be free from the ideological captivity of left and the right, of theists and atheists. The law-gospel hermeneutic provides a framework for showing how theology and science are at once distinct activities, yet, in mutual service to one another as humanity struggles with it’s calling to be God’s steward of the Creation. This notion of stewardship is stated ever so clearly in one of the Offertory Prayers of the Lutheran Book of Worship. Let us pray it: “Blessed are you, O Lord our God, maker of all things. Through your goodness you have blessed us with these gifts. With them we offer ourselves to your service and dedicate our lives to the care and redemption of all that you have made, for the sake of him who gave himself for us, Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

References:

1 See Stephen Jay Gould, Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life (New York: Bantam Books, 1999): “Science tries to document the factual character of the natural world, and to develop theories that coordinate and explain these facts. Religion, on the other hand, operates in the equally important, but utterly different, realm of human purposes, meanings, and values — subjects that the factual domain of science might illuminate, but can never resolve. Similarly, while scientists must operate with ethical principles, some specific to their practice, the validity of these principles can never be inferred from the factual discoveries of science.”

2 Michael J. Behe, Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution (New York: The Free Press, 1996), 39-40, 42-45.

3 “Methodological naturalism” is the idea that scientific knowledge of the natural world can advance only by only a strict observation of natural or material causes, the natural chain of cause and effect, which requires the suspension of any idea of supernatural causes or special intuition. It does not necessarily deny the existence of the divine or the supernatural, but rather asserts that the supernatural is not subject to the same scrutiny as the natural. “Philosophical naturalism,” on the other hands, denies the existence of the supernatural (it is atheistic in outlook) and assumes that everything can be ultimately understood in terms of material, natural causes. See for example, Ronald L. Numbers, “Science without God: Natural Laws and Christian Beliefs” in When Science and Christianity Meet, edited by David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 266, 282.

4 One of the most thoroughgoing exponents of this position is Daniel C. Dennett, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: evolution and the Meanings of Life (New York: Simon & Schuster: 1995).

5 For a more thorough explanation of this see Steven C. Kuhl, “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea … and St. Paul’s” in Creation and Evolution edited by Robert Brungs, S.J. (St. Louis: ITEST Faith/Science Press, 1998), pp. 77- 104 and 174-177.

6 Helpful texts for getting at some of the scholarly (“historical critical”) debate and consensus on the biblical texts include Bernard W. Anderson, editor, Creation in the Old Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984), John Reumann, Creation and New Creation: the Past, Present and Future of God’s Creative Activity (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1973), Brevard S. Childs, Biblical Theology of the Old and New Testaments: Theological Reflection on the Christian Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992), and Claus Westermann, Creation, John J. Scullion, S.J. translator (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1974).

7 This touches on the relationship of Physics, cosmology and theology. An excellent discussion on the variety of issues relating to modern Physics and Theology is available in Mark William Worthing, God, Creation, and Contemporary Physics (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996).

8 See, for example, Phyllis Trible, God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1978).

9 Edward L. Larson, Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory (New York: Random House/Modern Library Edition, 2004), p. 12-13.

10 In a very basic way, the biblical message sees no fundamental difference between atheism (disbelieving in the existence of God altogether), idolatry (replacing God with the things of this world), and religion that uses the name of the true God “in vain,” that is, that uses God’s name or being to advance one’s own aims rather than God’s. In the end, all of these are strategies to place some kind of human aim over God’s aim.

11 The civil function of the law represents that aspect of the critical process out of which secular authority emerges and evolves. It is itself steeped in paradox. Humanity as a whole is drawn into participating in its own self-criticism, a reality symbolized in the Genesis text by Adam and Eve’s reciprocal critique of one another. Today, Critical Social Theory stands as one expression of secular thought and philosophy that is especially focused on this dynamic. See, for example, Michael Walzer, Interpretation and Social Criticism (Cambridge, Mass. and London, England: Harvard University Press, 1987).

12 See, Erich W. Gritch, A History of Lutheranism (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2002), p. 194. It is perhaps an oversimplification to say that Walther’s work “On the Proper Distinction Between Law and Gospel is directly against Schmucker. It presupposes Walther’s engagement over the course of his career with many issues including debates over the nature of election and the office of the Ministry. What is significant is that the proper distinction of law and gospel stands out as the key hermeneutic for adjudicating issues of theology. In that sense it is not one doctrine among many but a hermeneutic. See also https://crossings.org/archive/ed/CFWWalther.pdf for a discussion of Walther’s theses on Law and Gospel as they relate to the issues that were stirring in the Missouri Synod controversy of the 1970s.

W2_Kuhl_Creation_Redemption (PDF)