Co-missioners,

On this Maundy Thursday we send along a few items for your devotional reflection on the mission of Christ Crucified and your role as one his cross-bearing agents.

Peace and Joy,

The Crossing Community

Looking at the Passion through the Wrong End of Exodus, and Other Notes for Holy Week

by Jerome Burce

The wrong end of Exodus, the Bible’s second book, is the one that hardly anybody bothers to skim, let alone to study.

Or perhaps I should say that few if any Christians do this. It may well be that Jewish readers, more reverent, are less inclined to bypass a stretch of Torah on the grounds of its stultifying tedium and apparent irrelevance to anything that matters today. But here I merely guess.

As for me and my irreverent house, it was only this Lent, after thirty-eight plus years of service as a pastor, that I finally got around to reading through this section with a measure of care; and the only reason I did that was to satisfy the expectations of the twelve or so earnest and thoughtful students of Scripture, most of them in their 70s or beyond, who comprise my Wednesday morning Bible class. Beginning last fall, we had read our way through the first thirty-four chapters of Exodus. When they caught me musing out loud about skipping the rest, they put their collective foot down. “Let’s finish,” they said. And we did.

So why the prior musing? See for yourself. Those last chapters of Exodus, 35 to 40, present an account of the building of the tabernacle. It exults in detail, details being the point. I mean the details laid out at meticulous, mind-numbing length in the set of design plans that God delivers to Moses in chapters 25 to 31. This, after all, is to be God’s dwelling, and God knows what God wants in a God-worthy tent, to say nothing of the clothes that will hang in its priestly closet or the aromatics that will perfume the place. No one who has spent a heap of years dreaming about the dream house she’ll build when the lottery ticket hits can quibble about this. “Do it my way,” says she, first to architect, then to builder; and when the ticket does hit, do it that way they will if they want to get paid. Detail is of the essence; attention to it even more so.

So guess what happens when you knuckle down as a reader and start attending to those details. Things pop out—all kinds of things.

The popping starts when you look at the way material is arranged in those final fifteen chapters. For example, while we notice immediately how surpassingly picky and demanding God is—all those chapters, all that detail—we also see how strangely gracious God is when it comes to construction schedules. This shows up in a double repetition of the Sabbath commandment, once at the end of chapter 31 as God wraps up his instructions, and again at the start of 35 when the building begins. God cares for laborers, especially his, and no one shall be worked to death on getting this project done. One wonders if Solomon and Herod remembered this when they built their temples. One also doubts it. (“Come to you weary, burdened ones, and I will give you rest.” So says Jesus in Herod’s day.)

Between these major sections—instruction here, construction there—lies the episode of the golden calf. This arrangement too is surely deliberate. It reminds us first that God’s plans are always at the mercy (so to speak) of a wretched work force, not only undependable but “stiff-necked,” as both God and Moses will describe this particular batch of them as the episode unfolds. But this revelation, if one can call it that—as if we weren’t intimately familiar with the stiffness of our own necks—serves all the more to highlight the wonder of the ensuing construction section. Lo and behold, the chastened rebels knuckle down to execute exactly what God asks of them, however finicky and onerous the specs happen to be. Again, guess what? They do it well. So very well.

Between these major sections—instruction here, construction there—lies the episode of the golden calf. This arrangement too is surely deliberate. It reminds us first that God’s plans are always at the mercy (so to speak) of a wretched work force, not only undependable but “stiff-necked,” as both God and Moses will describe this particular batch of them as the episode unfolds. But this revelation, if one can call it that—as if we weren’t intimately familiar with the stiffness of our own necks—serves all the more to highlight the wonder of the ensuing construction section. Lo and behold, the chastened rebels knuckle down to execute exactly what God asks of them, however finicky and onerous the specs happen to be. Again, guess what? They do it well. So very well.

This, I think, is the greater point that the arrangement of these chapters is driving at. It makes us notice how for once Israel delivers in an eruption of astonishing obedience; though it’s only the obedient reader, willing to wade through a sea of mind-numbing repetition, who will tumble to this. Well, of course that’s how it works. How else would God arrange it? As it happens, when the septuagenarian students finally shame their stiff-necked pastor into wading with them, he starts at last to see how Israel, like fictive Camelot-to-come, is shining momentarily as a beacon of hope for the world.

So one starts at chapter 35, with an offering so great to this dauntingly expensive project that Moses is finally compelled to tell the people to quit contributing. There is enough—much more than enough—to get everything done. (Since when has any rapacious mega-pastor with mega-projects in mind been moved to tell the folks to quit writing checks?) After this, and still in 35, comes a second introduction (cf. chap. 31) to the project managers, Bezalel of Judah and Oholiab of Dan, representing what will come to be the southern and northern extremities of Israel. “We are in this together”—so says that detail. Now starts the construction and manufacture of building, furnishings, and other accoutrements. That’s in chapters 36 to 38, where the specifications laid out in the prior instruction section, chapters 25-31, are repeated more or less line by line. It’s as if one is working through a long, exhausting checklist: “Done, done, done.”

Now the interest heightens. In chapter 39 we hear how the obscenely expensive priestly vestments were woven, dyed, and put together, again in strict keeping with God’s prior instruction. A short summation of the entire project follows. As the chapter unfolds a phrase recurs. This, that, and—at last—the whole thing was done “just as the LORD had commanded….” We hear this said seven times. Chapter 40 starts with God telling Moses, again in detail, to set the tabernacle up. Now comes a second report that either Moses or the people did “as the LORD had commanded Moses.” Again we hear this seven times.

Seven is the perfect number, established in creation (Ex. 20:11). What we find at the end of Exodus is a perfect obedience. Perfection brings perfect consequences. Thus the closing verse of 39, packed with echoes of Genesis 1:31—2:3: “When Moses saw that they had done all the work just as the LORD had commanded”—seventh repetition—”he blessed them.” And even better: the seven-fold litany in chapter 40 is capped with the statement: “So Moses finished the work” (v. 33b, again echoing Genesis). And with that—voila! “The cloud covered the tent of meeting, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle “(40:34). This is God settling in to keep the people company on their journey to the land of promise—the same God, lest we forgot, who had hovered on the verge of wiping them out as they danced around their calf (32:10).

About the cloud, this wondrous sign of God’s presence, at once dreadful and full of promise: 40:38 adds the note that “fire was in the cloud by night.” A member of that Bible class I spoke of is a mother, grandmother, and a retired second-grade teacher. I pass along her astute observation: “It’s as if Israel in that perilous desert had its very own night-light at the edge of the camp,” she said. “Such a comfort it must have been when people peeked from their tents in the darkness and saw its glow.”

Our comfort in 2019 is the cross—or rather, the One who hung on a particular first century cross with the perfect obedience that Israel couldn’t maintain. This, I think, is how the wrong end of Exodus points to Jesus’ passion and helps us poke around in the depths of its significance. I bring this up too late for preachers’ Good Friday homilies this year, but not too late, perhaps, for your personal prayer and reflection tomorrow.

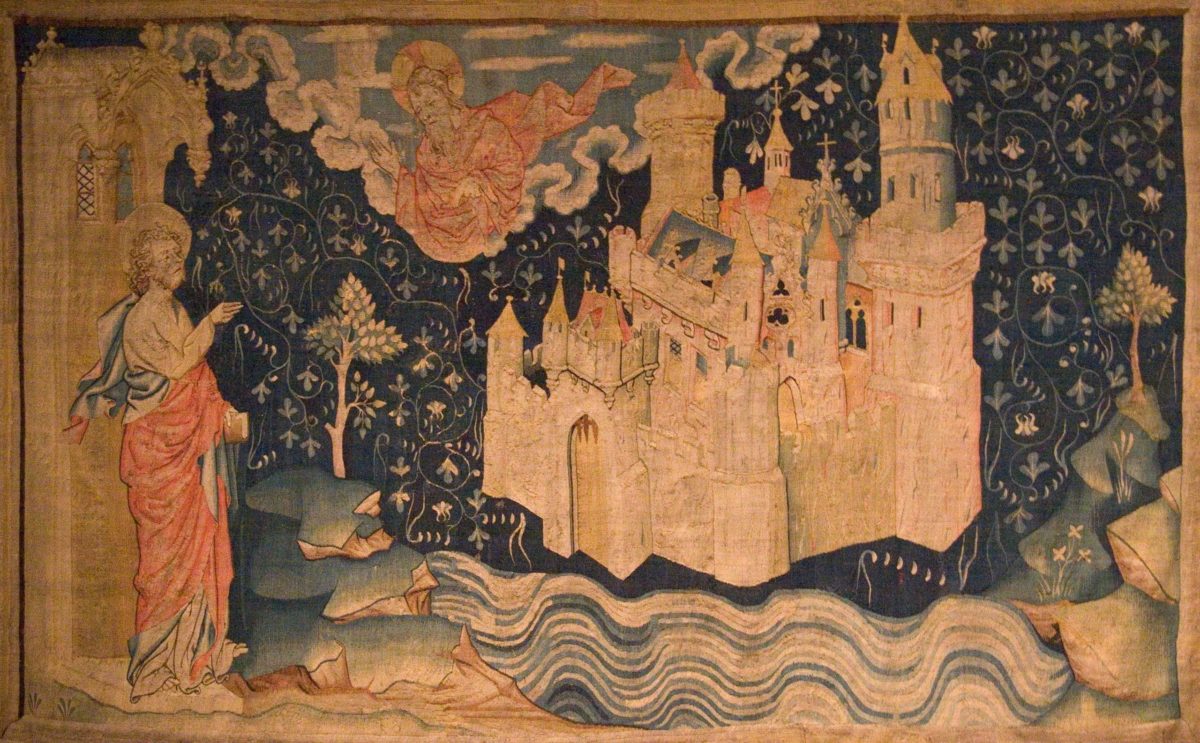

![]() Tomorrow’s great text is the Passion according to St. John. Let your musing focus there. Attend to the details. As you do, let your mind roam as widely in the rest of John’s Gospel as your memory will allow. For example, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (1:14, NRSV). More literally, “The Word was made flesh—impermanent, fleeting flesh; oh-so precious nonetheless—”and camped out among us.” That’s end-of-Exodus tabernacle talk, a point underscored in the subsequent clause when the evangelist says, “we beheld his glory,” that of the Father’s One-and-Only, “full of grace and truth.”

Tomorrow’s great text is the Passion according to St. John. Let your musing focus there. Attend to the details. As you do, let your mind roam as widely in the rest of John’s Gospel as your memory will allow. For example, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (1:14, NRSV). More literally, “The Word was made flesh—impermanent, fleeting flesh; oh-so precious nonetheless—”and camped out among us.” That’s end-of-Exodus tabernacle talk, a point underscored in the subsequent clause when the evangelist says, “we beheld his glory,” that of the Father’s One-and-Only, “full of grace and truth.”

All this is said from a post-Easter perspective. Looking back, John sees “the light of the world”(8:12) shining in the darkness of sin and death, a darkness filled with the noise of treasonous chatter and outright rebellion. Israel murmurs again, its single spasm of brilliant evanescent obedience now fogged in the haze of mythic memory. As for the nations, they rage as ever. For all their sakes, ours too, the Obedient One stumbles up Skull Hill “carrying the cross by himself” (Jn. 19:17). Why? “To do the will of him who sent me and to complete his work” (Jn. 4:34), the scope and nature of which has already been signaled by the seven great signs of the first eleven chapters, each done, done, done. So now the last and greatest doing of them all, as he gives his flesh “for the life of the world” (Jn. 6:51).

Remember how Moses “finished the work”? The jump from that to Jesus’ last word is impossible to avoid. “It is finished,” he says, as in all things accomplished once and for all in perfect keeping with the Father’s specs and expectations (Jn. 19:30). Comes the perfect consequence. Easter erupts, Christ raised from the dead to complete the magnificent promise of Revelation 21:3, uttered as the glory of New Jerusalem settles on earth. Again literally (versus the watered-down prose of the NRSV): “Look! God’s tabernacle is among humankind. God will camp with them. They will be his people and God himself will be with them.”

So peek from your tents in today’s deep night. Sure, it’s ugly dark out there. But notice that glow in the offing, the wondrous light of God in Christ Crucified, at once dreadful yet so full of promise. Emmanuel. God with us. All things accomplished for your children’s salvation. Completed. Done. Let hearts be cheered!

And with that, having hardly begun, I turn these things over to you. You could do a lot worse tomorrow than to sit for a couple of hours with Exodus in one hand, John in the other, and a prayer to the Holy Spirit for a patient mind, an obedient heart, and eyes that will see.

+ + +

Ever so quickly, a couple of other suggestions for your meditation this weekend, and a warning too.

- “The Cross,” by John Donne. I stumbled across this entirely by accident some weeks ago. It bears an entire Lent of once-a-day reading. Donne knew the sinner’s heart as few do, and yes, he uses Christ to comfort and encourage it.

- For Holy Saturday: John Chrysostom’s Paschal Sermon, first preached in the early 400’s and still read by liturgical stipulation in Orthodox churches every Easter, or so I gather. Chrysostom means “golden-tongued.” No wonder they called him that. One reads. The heart sings.

- The truth is at issue in tomorrow’s encounter between Jesus and Pilate. It’s still at issue in tomorrow’s encounter between Jesus and 21stcentury Americans. For some heart-sagging insight on that, see David Brook’s “Five Lies Our Culture Tells,” published in the New York Times this past Monday. For even more—much more—get a copy of David Zahl’s Seculosity: How Career, Parenting, Technology, Food, Politics, and Romance Became Our New Religion and What to Do about It, new this month from Fortress Press. “Tracking” is the term we use at Crossings for the work that Brooks and Zahl are doing here. No one does it better.

- Back in the 1970’s the editors of Lutheran Book of Worship ruined one of the best of the classic Good Friday hymns in the German Lutheran tradition, “Jesu, Meines Lebens Leben,” or as Catherine Winkworth rendered it in the 19th century, “Christ, the Life of all the Living.” In Winkworth’s version the closing refrain is this: “Thousand, thousand thanks shall be, dearest Jesus unto Thee.” Itching to update the English, the LBW folks turned it into “Thousand, thousand thanks are due, dearest Jesus unto you.” How, pray tell, did they miss that huge difference between “shall be” and “are due”? The first is glorious Gospel. The second is grinding Law. Bear that in mind if a service planner afflicts you tomorrow with the revised version. Refuse to sing it. Think Winkworth instead. (I’ve been meaning for years to gripe about this in print. Out comes my personal checklist: “Done!”)

Thursday Theology: that the benefits of Christ be put to use

A publication of the Crossings Community

You must be logged in to post a comment.